Building National Pharmacare on a Flawed Foundation

Anmol Gupta

February 6, 2023

Universal health care is a source of national pride for most Canadians, but it has long been missing a critical component: pharmacare.

Medicare was never meant to exclude drug coverage, and despite six decades of federal commissions and reports recommending the fix, a pan-Canadian program has yet to see the light of day. In its place, a patchwork of provincial and private plans has emerged, creating a complex and opaque system that continues to leave many Canadians behind.

Today, 7.5 million Canadians lack insurance coverage for their outpatient medicines, while nearly one in four skip or ration their medications due to cost. And as a nation, we spend more and more each year to provide life-saving drugs.

A national program would aim to alleviate these disparities, allowing the federal government to singularly negotiate lower prices on behalf of all Canadians. The debate on implementing such a program has ebbed and flowed over the years, more recently being overshadowed by the clash between the premiers and Ottawa over health transfer payments. Nevertheless, the Liberal-NDP confidence-and-supply agreement continues to place political pressure on Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Health Minister Jean-Yves Duclos to put forth a pharmacare plan this year if they seek to keep the government whole.

Currently, one-third of Canadians on public drug plans rely on a patchwork of federal and provincial players that determine a drug’s safety, value, price, and availability. Federal agencies such as Health Canada and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) first determine if a drug is safe and of value to patients. If approved, the provinces and territories collectively negotiate a price through the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA), in a process that can take up to two years. Once an agreement with a manufacturer is reached, individual provinces and territories decide if they will accept the final price and add the drug to their list of reimbursed medicines, known as a formulary.

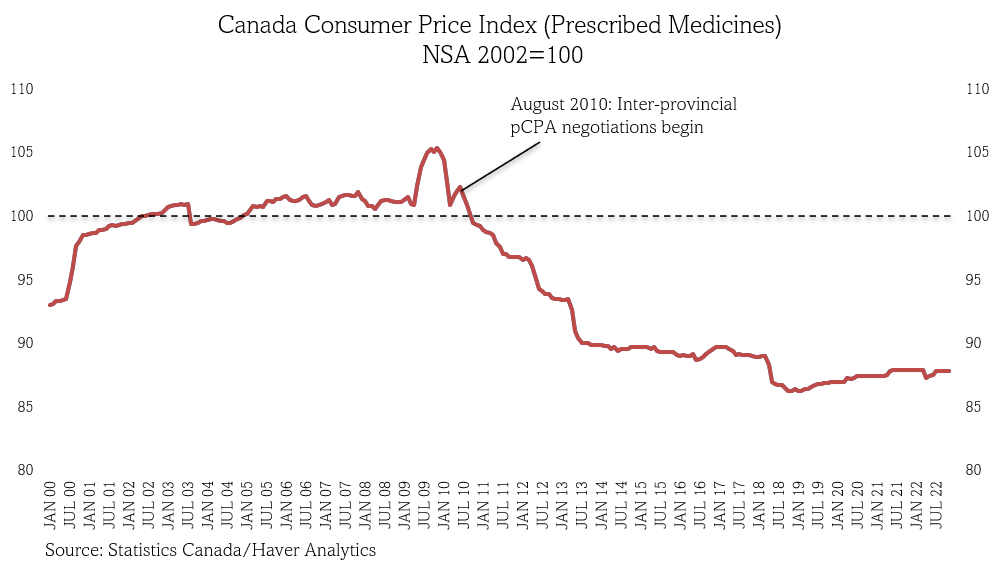

To its credit, this system has saved Canadians significant money. Today, we pay 13 percent less on drugs, compared to 2002, saving the nation $3 billion annually.

Still, Canadians continue to pay some of the highest prices in the world — third only to the United States and Switzerland — and we have little information to know if these agencies are working as well as they could, given their lack of transparency and oversight.

Despite 30 years of operation, questions remain about the evidence that CADTH’s experts rely upon to determine a drug’s value to patients, especially those with rare diseases. CADTH has also regressed in providing meaningful transparency about its final decisions, abruptly discontinuing efforts in 2012 to publicize its recommendations in plain and easy-to-understand language.

The pCPA has its own issues. The Council of the Federation and Parliament’s Standing Committee on Health have both found that the pCPA offers little clarity on how it negotiates with manufacturers. Negotiations are prematurely closed or never initiated for nearly one in four CADTH-approved medicines, for reasons ranging from backlogs of new products to stalled discussions with manufacturers. Regardless of the reason, pCPA offers little by way of publicly explaining its decisions or offering steps it will take to resume price discussions on behalf of Canadian patients. Drug coverage remains a provincial jurisdiction, and even when the pCPA is successful in reaching a price, the provinces and territories occasionally make different funding decisions – with little public explanation.

As recommended by Parliament’s 2018 Standing Committee and Health Canada’s advisory council for pharmacare implementation, Canada’s least disruptive path to national pharmacare is likely through the expansion of these existing agencies. But failing to make these agencies accountable to the patients who depend on them risks us investing in a national program with a weak foundation.

Even if Canada can overhaul CADTH and pCPA, the federal government will face the added challenge of unifying the formularies of 13 provinces and territories and thousands of private plans. Many patients will likely lose coverage of the specific medications they depend on, and the federal government will need to be forthright about the tradeoffs it is asking of Canadians. From Ontario to New Brunswick countless examples of governments stripping away drug coverage and leaving patients without information or alternatives provide critical lessons on the need for upfront transparency.

Despite the political pressures, there remain significant hurdles in the way of national pharmacare, the most obvious being its $15.3 billion price tag and the current inflationary environment. It remains uncertain whether 2023 will indeed be pharmacare’s year, but the idea of universal drug coverage is unlikely to disappear anytime soon.

Either way, planning for pharmacare unveils the dire need for transparency in the current system — something our federal and provincial leaders might just be able to work together to fix. Doing so will only strengthen the foundation needed for Canada’s eventual transition to universal pharmacare.

Anmol Gupta is a Master of Public Policy candidate at McGill’s Max Bell School and a Doctor of Medicine candidate in the United States. Anmol has an interest in improving global health governance and using policy to increase equitable access to medicines.