Budget 2024: Plotting a Return to Canadian Competitiveness

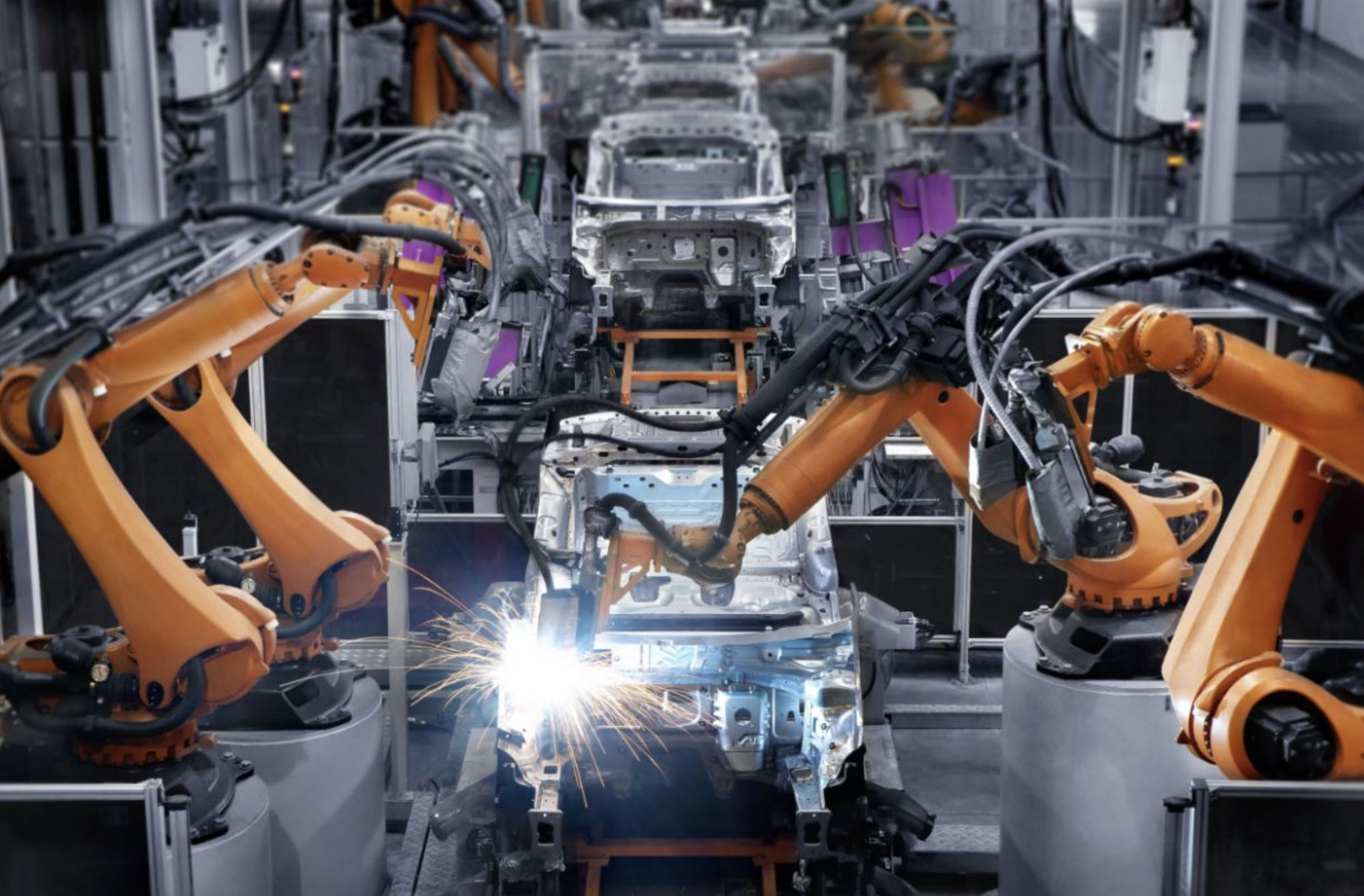

Universal Robots

Universal Robots

By Kevin Lynch and Paul Deegan

April 13, 2024

“Without a much stronger economy, the ambitions of politicians of all parties for a better economic future for our citizens will come to naught. Yet neither of the two main political parties has a properly worked-out plan of action to improve the economy – or even any prospect of developing one.” These words, from Policy Exchange, a leading conservative UK think tank, motivate their new report – Economic Transformation: Lessons from History – and its call for a transformation of the British economy to reverse its anemic growth in living standards over the last fifteen years.

Tellingly, Canada’s weak growth in GDP per capita since the global financial crisis of 2008 has mirrored that of the UK, averaging roughly 0.5% annually in each country, but actually turned negative last year. This serial underperformance stands in sharp contrast to the United States and much of the European Union. Reviewing the Policy Exchange study, Martin Wolf of the Financial Times warned: “In the long run, continued stagnation creates severe social and political challenges: higher taxes; worsening quality of public services; pervasive disappointment; and zero-sum struggles for advantage.”

Where is a similar sense of urgency and purpose in Canada?

Like the UK, we have a competitiveness crisis in Canada – weak growth in living standards is the painful consequence. Productivity growth in Canada has been relatively poor since the start of this century, resulting in an overall productivity level that is lower than almost all Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries. More worrisome still is that average business sector labour productivity growth in the United States since 2000 has been more than double Canada’s, despite the highly integrated nature of our economies. And American productivity growth has rebounded strongly since the pandemic, unlike our experience in Canada.

Canada’s competitiveness crisis has, unfortunately, many contributors. We have an excessive regulatory burden, which acts as a stealth tax on corporate activity and hinders our ability to build trade-enhancing infrastructure. We have a poor track record on innovation, with one of the worst private-sector rankings of R&D spending as a share of GDP across all OECD countries, and few firms that are global high-tech leaders relative to our peers. We are still unable, after more than a century, to rid ourselves of internal trade barriers that act as an own- goal on competitiveness. We have a stronger rhetorical commitment to competition than what our competition law and regulations indicate. We have a corporate sector with one of the lowest capital investment-to-GDP ratios among our OECD competitors. We have inefficient and ineffective government delivery of core goods and services. And, we have corporate and top personal tax rates that are less competitive globally than they were a decade ago and a complex decarbonization policy regime with political and public credibility issues.

Canada needs a clearly articulated competitiveness strategy and a compelling vision of economic transformation leading to sustained growth in Canadian living standards.

Compounding these competitiveness impediments, particularly for a trading nation such as Canada, are emerging international challenges. With over 75% of our trade going to the United States, the 2026 renegotiation of CUSMA and the possibility of a Trump 2.0 presidency, with his threats to impose across-the-board tariffs of 10%, are a real and present danger to our competitiveness. More broadly, rising protectionism and aggressive industrial policies in the U.S., China and elsewhere are creating fragmentation in global markets and supply chains, adding costs and risks. And today’s troubling geopolitical tensions only add to these global risks for Canada.

As challenging as this environment is, it is aggravated by short-termism and complacency. Handwringing is not a strategy to get out of our competitiveness mess, and a multi-faceted, multi-year transformation, not tinkering, is clearly needed to get Canada’s growth in living standards back on track.

What can be done? The Policy Exchange study looked at the transformation lessons from eight countries that have made major and successful growth and productivity pivots: Thatcher’s Britain, postwar France and Germany, the Irish Celtic Tiger, post-USSR Poland, postwar South Korea, Hong Kong, and Singapore.

The study argues that these transformations contain a number of common and useful lessons for today: a clear strategy is essential; fiscal prudence is a necessary-but-not-sufficient condition for success; low inflation helps but is not decisive; taxation rates matter; high rates of investment are critical; competition is a key driver of efficiency; focus on a package of measures, particularly micro ones, not one-off interventions; and, strong leadership and a strong team are essential. The study also found that early successes, combined with a compelling narrative for the future, were essential to building and retaining political support for transformation.

Translating these lessons into the current Canadian reality is challenging, but one thing is clear: Canada needs a clearly articulated competitiveness strategy and a compelling vision of economic transformation leading to sustained growth in Canadian living standards.

The upcoming federal budget and the political and public debate around it provide such an opportunity. Why not consider a package of low-fiscal cost, high competitiveness impact measures such as scrapping internal trade barriers, reducing the regulatory burden, strengthening competition policy, doubling down on trade diversification by negotiating trade arrangements with allies and complementary economies, including Japan, Germany and Britain, and bringing in credible fiscal anchors to rebuild our resiliency. These would have the advantage of being solely within the control of governments, they would be fiscally responsible, and would provide credible early successes to help launch a longer-term transformation strategy.

Hon. Kevin Lynch was Clerk of the Privy Council and vice chair of BMO Financial Group

Paul Deegan was a public affairs executive at BMO and CN, and he served in the Clinton White House