Budget 2024: Canadians Need a National Flood Insurance Program

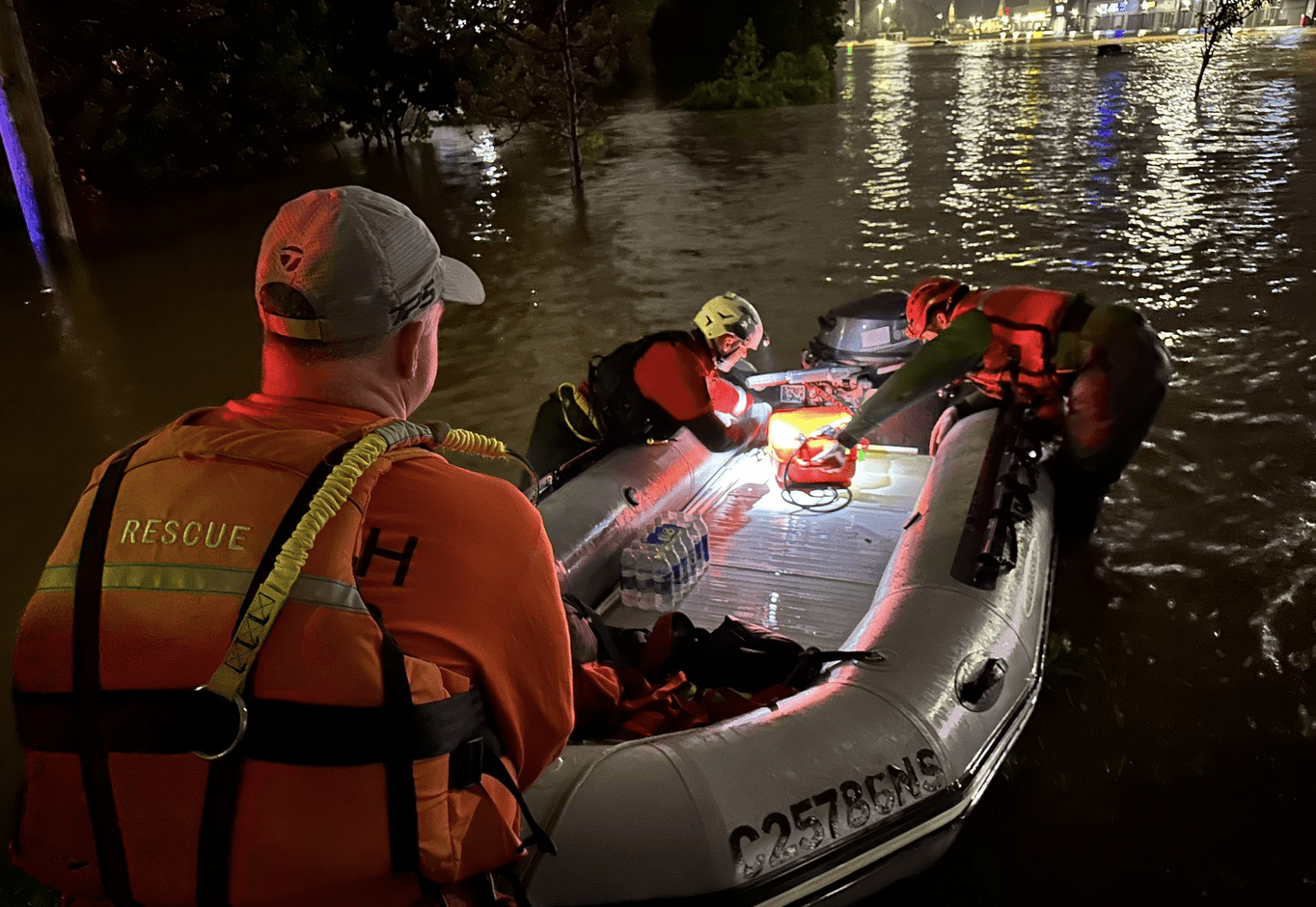

Flood rescuers in Nova Scotia, July, 2023/Halifax SAR

Flood rescuers in Nova Scotia, July, 2023/Halifax SAR

Leah Brodovsky

April 11, 2024

From the wildfires in British Columbia to the floods in Nova Scotia, 2023 saw a significant number of natural disasters. For two consecutive years, insured damage from natural catastrophes and severe weather events exceeded $3 billion. As climate change exacerbates the frequency and severity of these events, flooding is recognized as the most common and costly natural disaster in Canada.

Canadians are starting to know this all too well. Ten percent of Canadian homes (roughly 1.5 million) are in high-risk flood zones. The federal Task Force on Flood Insurance and Relocation estimates the total residential flood risk at $2.9 billion per year, with 90 percent of the risk tied to those 1.5 million homes.

The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is a public-private partnership between the federal government and the property and casualty insurance industry. Its policy objective is to provide “adequate and predictable financial compensation” for individuals experiencing various types of flood damage in high-risk flood zones. It aims to be affordable for individuals in these areas while reducing the burden on taxpayers as the impact of climate change continues to escalate.

The federal government acknowledged the need for an NFIP by granting seed funding in the 2023 federal budget. The 2024 federal budget being tabled April 16th will reveal whether the NFIP will be granted the operational funding necessary for its implementation. The Insurance Bureau of Canada (IBC) has called the program’s implementation “the single most important step Canada can take to better protect homeowners from the financial risks of climate change today.”

Most G7 countries, including the United States, United Kingdom, and France, already have NFIPs in place. It is time for Canada to implement its own.

Defining the Issue

1) Limited insurance availability and high costs: The need for an NFIP stems from the lack of availability of private flood insurance for the majority of the 1.5-million homes in high-risk areas. Insurers calculate the risk to be too great, meaning the payouts to insurance holders would surpass their premiums. In the rare cases where private flood insurance is available, risk-based premiums as high as $10,000 to $15,000 can dissuade homeowners, leaving them vulnerable. This creates a flood-damage cost burden for those homeowners and even in the case of severe events, government disaster financial assistance (DFA) programs can be inconsistent.

2) Moral hazard: The issue with the current DFA programs is that, simply put, the DFA provides “free” flood insurance paid for by taxpayers when applicable. This creates a moral hazard, where homeowners are disincentivized from purchasing insurance or reducing their risk. At the municipal level, local governments approve land-use decisions that can increase flood risk while increasing their tax revenues. This forms a “perverse incentive structure,” where governments are expected to provide essentially free DFA, regardless of high-risk municipal development decisions or inaction from homeowners.

3) Equity considerations: Indigenous communities are disproportionately affected by flooding across Canada. A report from the Canadian Red Cross identified Indigenous Peoples, people with disabilities, low-income residents, and new immigrants as vulnerable groups at the highest risk of experiencing injury, death, and damages during a disaster. The proposed NFIP will have to consider these vulnerable groups in providing equitable insurance coverage.

Fostering an Environment for Success

While an NFIP is greatly needed, other complementary tools must be considered to support flood mitigation and adaptation.

Approximately 94 percent of Canadians living in high-risk flood areas are unaware of their flood risk. This means that even when flood insurance is available, individuals may not purchase it due to their lack of awareness or assume that it is covered by their home insurance. Education is needed to empower Canadians, particularly for individuals looking to rent or purchase a home and those purchasing or renewing insurance policies. Policies that support flood-risk transparency through flood-risk mapping, disclosure, and pricing should be considered.

All stakeholders, from individuals to municipal, provincial, territorial, and federal governments, have a responsibility to reduce flood risk. At the homeowner level, this could include installing a back-up valve. For municipal governments, policies to prevent new development on high-risk floodplains are needed. For the federal government, updates to National Building Codes and effective flood relocation policies can support adaptation. This creates a more resilient environment, enhancing the effectiveness of the NFIP.

If the NFIP is launched, DFA funding for high-risk areas will need to be discontinued in order to not undermine the national insurance program. A transition plan will be necessary to disincentivize new or further development in high-risk flood zones.

By addressing affordability concerns and prioritizing flood risk mitigation and adaptation, an NFIP can provide Canadians with financial security in the face of climate change. The time to act is now.

Leah Brodovsky is a Master of Public Policy candidate at the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University. Leah holds a BSc. Honours Food Science from the University of Guelph. Her policy focus is the intersection of climate, health, and digital policy.