Budget 2022: Getting the ‘House’ in Order

Douglas Porter, Robert Kavcic

April 7, 2022

Overview: Tax & Spend, to a Degree

Faced with a myriad of ambitious plans but also beset by the fastest inflation in more than three decades, the 2022 Federal Budget attempts to strike a middle ground. It opts to add a moderate increase in spending, while relying on stronger underlying economic activity and some tax measures to slightly improve the deficit track. The initial to-do list for this Budget was formidable with earlier commitments on child-care funding, emissions reductions, and housing, but was recently extended to include dental care and defence spending. To accommodate this raft of priorities (and there was indeed a full raft in this budget), spending has been spread out over a number of years on some files, a variety of tax measures have been enacted—with some details to be determined—and the higher revenue base has been tapped. As a result, the deficit and debt projections from late last year have improved overall, even with the new spending announcements. However, given the already extreme pressure on inflation, we judge that the modest improvement in the deficit outlook could have been more ambitious in repairing the pandemic’s fiscal damage. And, while most were probably braced for even more spending, net policy measures will still add roughly 0.3 ppts to growth this year, at a time when an inflation battle is well underway.

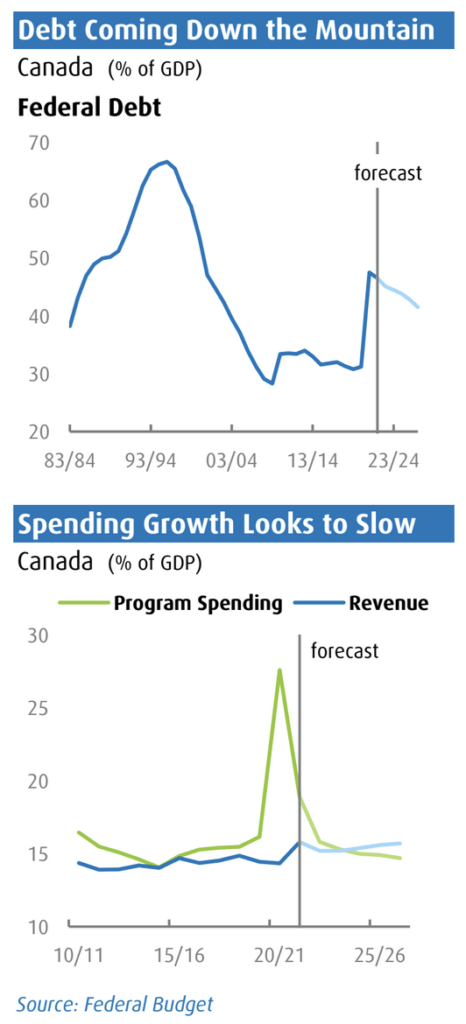

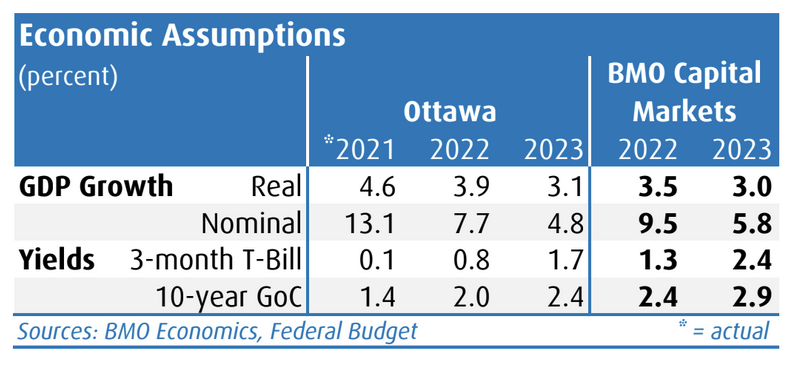

This budget was billed as fiscally responsible, since the debt/GDP ratio is projected to remain on a downward path (after a huge jump in 2020). But, a key reason that Ottawa was able to hold the line on its deficit and debt projections is that revenues have swelled led by the recent run-up in resource prices (a 40% rise in the past four months alone for the Bank of Canada’s commodity price index). To be clear, this has supercharged nominal GDP far beyond prior expectations, but has done nothing to boost the outlook for real GDP. In fact, looking at how the economic forecast assumptions have changed since December reveals that while the outlook for nominal GDP has been raised by nearly 3 percentage points this year (from 6.6% then to our latest call of a whopping 9.5%), real growth for this year has actually been shaved (from 4.2% to 3.5% over the same period). Essentially, revenues have been boosted by a short-term rush of higher inflation—but that’s not a healthy development, as eventually costs will also face upward pressure, including borrowing costs.

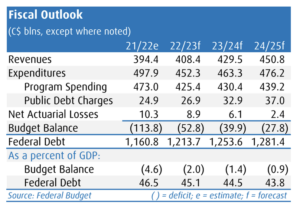

As we have long maintained, fiscal policy has a very big role to play in controlling inflation as does monetary policy. And, with inflation clocking in at a 30-year high of 5.7%, and likely headed higher, there is some urgency for the task at hand. The Bank of Canada is in the early days of reversing course, with potentially rapid tightening measures on the near horizon—we see the overnight rate rising 150 bps by year-end to 2.0%, higher than pre-pandemic levels. For fiscal policy, the appropriate stance with the economy operating at full capacity and revenues rising rapidly would have been to let the windfall largely flow through to the bottom line. Instead, the focus in the Budget is channelling a healthy portion of the revenue windfall to new priorities, while also layering on additional net tax increases. That said, a number of the new Budget Balance measures do commendably focus on the supply side of the economy, targeting Federal Debt 1,160.8 1,213.7 1,253.6 1,281.4 investment in some sectors, as well as the availability and mobility of labour.

Key Messages

- Budget deficit falls to $52.8 billion in FY22/23, from $113.8 billion last year

- Debt/GDP tracks steadily lower, from 45.1% this year to 41.5% by FY26/27

- Net new stimulus of $7.4 billion this year; $29 billion over five years

- Full slate of measures aimed at housing supply and demand

- Economic assumptions are behind the curve, but risk around fiscal profile looks balanced

And, because some massive pandemic-era programs are rolling off, program spending does fall meaningfully this fiscal year. On balance, this fiscal policy calibration will keep the onus squarely on the Bank of Canada to control powerful inflationary pressures.

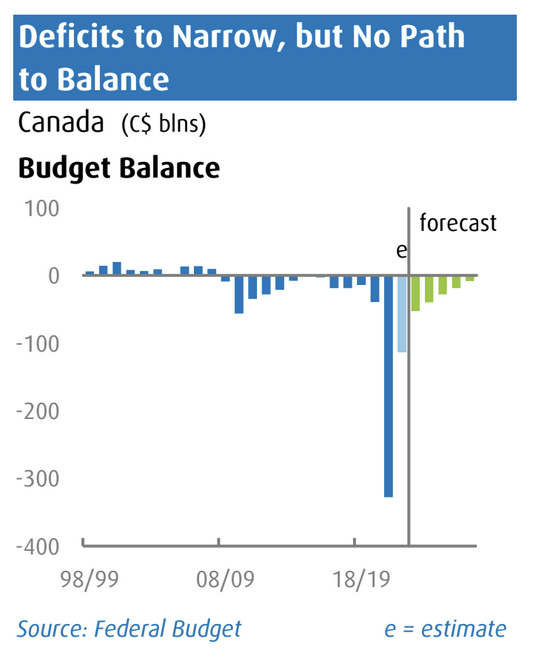

Fiscal Outlook: Finding Normal

The two opposing forces of a stronger-than-expected economy and new spending priorities lean in favour of the former, with the deficit track running better than expected in the Economic and Fiscal Update. The deficit is pegged at $52.8 billion in FY22/23 (2.0% of GDP), down from $113.8 billion in FY21/22 (revised meaningfully from $145 billion thanks to higher revenues). While that is well down from the record $328 billion at the depth of the pandemic in FY20/21, thanks to resurgent revenues and expired emergency programs, new spending measures keep the balance in the red through the forecast horizon.

Cumulatively, the total deficit between FY21/22 and FY26/27 is now running $50 billion smaller than in the prior fiscal update, alongside an $86 billion improvementfrom economic and fiscal developments. In other words, over the fiscal forecast, Ottawa has allowed roughly 60% of the improvement to flow to the bottom line.

Revenues are projected to rise 3.5%, to $408 billion in FY22/23, led by gains in personal income tax receipts. Meantime, program spending is projected to fall another 10% this fiscal year, as some one-time support measures roll off. Over the medium term, spending growth runs at a moderate pace around 2% per year through FY25/26. The track for program spending is actually less aggressive than some might have expected. In the five years pre-COVID, total spending averaged a steady 14.5% of GDP. This year, total spending will run at roughly 16% of GDP, before fading to around 15% late in the forecast. That’s still a noteworthy increase in government spending as a share of the economy, especially at a time when nominal output itself is surging on the back of rising prices, but it might not be as heavy as expected.

Revenues are projected to rise 3.5%, to $408 billion in FY22/23, led by gains in personal income tax receipts. Meantime, program spending is projected to fall another 10% this fiscal year, as some one-time support measures roll off. Over the medium term, spending growth runs at a moderate pace around 2% per year through FY25/26. The track for program spending is actually less aggressive than some might have expected. In the five years pre-COVID, total spending averaged a steady 14.5% of GDP. This year, total spending will run at roughly 16% of GDP, before fading to around 15% late in the forecast. That’s still a noteworthy increase in government spending as a share of the economy, especially at a time when nominal output itself is surging on the back of rising prices, but it might not be as heavy as expected.

The debt-to-GDP ratio will fall to 45.1% this year, from 46.5% in FY21/22, before declining gradually to 41.5% by FY26/27. The full track for the debt burden is running notably lower than expected late last year (the ratio for this fiscal year is pegged more than 2 ppts lower), thanks in part to surging

A Loose Fiscal Anchor

There remains no plan in place to balance the budget, and the ‘fiscal anchor’ is defined as a commitment to “unwinding COVID-19-related deficits and reducing the federal debt-to-GDP ratio over the medium term”. Recall that Ottawa laid out a set of ‘fiscal guardrails’ in the 2020 Fall Economic Statement, to assure that there would be some medium-term fiscal anchor to guide a return “to a prudent and responsible fiscal path”. Each of the employment rate, total hours worked and the unemployment level, the three “data-driven triggers” identified by Ottawa, have indeed fully recovered, and it’s clearly time to be more forcefully pinned to a firmer fiscal anchor. While the deficit track is slow to improve, the budget does show a consistent decline in the debt-to-GDP ratio. The issue with this as a fiscal anchor is that the debt-to-GDP ratio is not a hard anchor, and it is usually destined to jump when the economy (the denominator) stumbles. Indeed, before the pandemic, this anchor was steady just above the 30% mark, a level we’re not getting back to in this fiscal plan.

Economic Assumptions: Behind the Curve

As is the convention, the budget projections are based on the private sector consensus forecasts, but this round was put in place before some major dislocations on the growth, inflation and interest rate fronts. The budget is based on real GDP growth of 3.9% this year (we are now at 3.5%), 3.1% next year (3.0%) and then fading further to 2% in 2024 (2.7%). While real growth gets the focus, nominal growth is the big story and the driver of revenues. Ottawa expects nominal growth at 7.7% this year (we’re at 9.5%) and 4.8% in 2023 (5.8%). Based on our forecast, this would be the strongest three-year surge in Canadian nominal output since 1982. Indeed, the biggest forecast discrepancy in this document versus the reality on the ground today is an under-accounting of near-term inflation pressure. Interestingly, this might actually drive further revenue upside, and Ottawa estimates that a 1-ppt increase in GDP inflation adds $2.2 billion to the bottom line in the first year.

The only real downbeat note on the economic forecast is that borrowing costs are moving higher. The 10-year bond yield assumptions have been lifted slightly both this year and next, but are still roughly 0.4 ppts behind our current view. And, while the budget now builds in more aggressive Bank of Canada tightening, it still looks behind the curve relative to our current forecast. Again, this is simply a matter of the market moving quickly between the time the budget assumptions were locked in, and today. Finance estimates that a 1 percentage point rise in interest rates boosts the deficit by $5 billion in the first year, which could offset revenue gains.

Debt Management Strategy

With the deficit still large, Canada will remain an active borrower this year and, because of dynamics with quantitative tightening, the market will have plenty to absorb. Gross bond issuance is expected to fall to 7083/84 93/94 03/04 13/14 23/24 Spending Growth Looks to Slow Canada (% of GDP) $212 billion, down $43 bln from the prior year. After accounting for maturities, that pegs net issuance at $30 bln. While the issuance figure is down from prior years, keep in mind that the Bank of Canada is in the midst of shifting policy from effectively absorbing all the federal government’s net issuance early in the pandemic (i.e., in the big deficit year of FY20/21), to likely tightening through balance sheet runoff. In other words, the Bank will have roughly $85 billion of bonds maturing this year, adding to the amount that will need to be taken down by the market. Depending on any caps that are put in place, and at what amount, that could leave what could be the largest nominal net bond supply on record for the market to absorb.

Prior-year moves in the Debt Management Strategy to extend the term of the debt remains a theme, though issuance in the 10-year and 30-year sectors is set to decline in FY22/23. Planned issuance is $54 bln in the 10-year sector (25% of total) and $16 bln in the 30-year sector (8% of total), versus $79 bln (31%) and $30 bln (12%) respectively in the prior fiscal year. As well, $4 billion in ultra-long bond issuance is anticipated again this year. Meantime, 2-year issuance is the only sector set to see an increase, though it’s a relatively modest rise from $67 bln to $74 bln. And, combined 3-, & 5-year issuance will dip slightly to $58 bln. Benchmark sizes will decline in most sectors, consistent with the lower overall issuance. Treasury bill issuance is planned to rise to $213 bln which, along with a $28 bln cash drawdown, helped limit bond issuance. Ottawa will aim to continue the Green Bond program, with $5 billion in issuance targeted, dependent on market conditions.

Summary and Impact

This budget foregoes an opportunity for more significant fiscal consolidation, in exchange for another round of spending and tax increases. Fundamentally, this has raised questions of appropriateness. First, it is indeed questionable if continued new spending (aside from defence) is warranted at this stage of the cycle, with the economy clearly pushing against capacity constraints, and the Bank of Canada now actively battling persistently-high inflation. For example, some provincial governments are currently rolling out stimulative measures to counter inflation, and this budget adds to the mix. That said, a number of measures aim to spur investment and improve the supply side of the economy, which are worthwhile goals. From a credit perspective, a gradually falling debt-to-GDP ratio is again the fiscal target, but history reminds us that the ratio can deteriorate quickly, and some faster improvement would be prudent at this stage.

The market impact tends to be minor given how much these budgets get leaked in advance, and considering that many of the measures were already highlighted in the election platform. Broadly, the tax-and-spend nature of fiscal policy, even if more muted, along with persistent deficits, could be viewed as somewhat negative for the loonie, but Canada is not alone on this front and other major drivers (such as interest rates and oil prices) will dominate. For bond yields, still-elevated borrowing will now likely run alongside central bank quantitive tightening, leaving a large amount of issuance for the market to absorb. Finally, for equities, the financial sector was a clear target, but that should have been well anticipated, while major tax increases on oil & gas and REITs were absent, for now.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and Robert Kavcic is a senior economist with BMO Financial Group.