Budget 2020: Managing Risk and Uncertainty

Fiscal planning always contains an element of uncertainty. Budgetary policy at the federal level in Canada includes managing not just all the risks inherent in an economy subject to global trends—from capital flows to the coronavirus—but all that and the price of oil, too. Ahead of Budget 2020, former Parliamentary Budget Officer Kevin Page advises prudence.

Kevin Page with Kyra Carmichael, Nicholas Liban Dahir, and Hiba Khan

Finance Minister Bill Morneau is expected to table his first budget of a new government mandate in late March, just before the current fiscal year draws to an end. It is an important budget. The government needs to demonstrate it can be a steady hand on the tiller in a period where the waters are likely to

be choppy.

A ship’s captain confronted with difficult weather must make choices. One, the captain can slow headway and put the bow into the wind—approaching waves at an angle so not to unbalance the ship. Two, the captain can adjust course and seek shelter.

The economic clouds on the horizon are real. They are global in nature—coronavirus, slumping world trade, geopolitical tensions related to a host of factors including Brexit, the U.S. election and relations with China and Iran.

While it is early going, there is a good chance that markets and analysts have underestimated the potential negative economic impacts of the spread of the coronavirus. Global supply chains have already been seriously disrupted. As the disease spreads, the impact on supply chains will grow. Whether we are facing a global growth slowdown or a recession will depend on the spread of the virus and the impact on business and consumer confidence.

This is all playing out in the wake of a loss of economic momentum. Growth in North America and Europe was below expectations at the end of 2019—virtually no growth in Europe in the fourth quarter.

So, what does this mean for Budget 2020 strategy? We think it means the prudent course is for the ship’s captain, Finance Minister Morneau, to slow headway on platform implementation.

First and foremost, budgets are economic and fiscal plans. While the likelihood and timing of a global slowdown is uncertain (difficult to predict), the risks around growing imbalances in output, regional economies, investment and household debt in the Canadian economy are real. Short- and long-term economic imbalances create risk to stability and growth.

• All the growth in the economy since fall 2018 has come from the service sector. Bank of Canada Governor Stephen Poloz expressed concerns earlier this year that weakness in the goods sector may adversely affect the service sector.

• Economic situations are much weaker in energy producing provinces like Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland and Labrador.

• Household credit and mortgage liabilities relative to GDP sits at 165 percent in 2019, up from 100 percent in 2000. Debt service costs have risen significantly over the past two years.

• Real gross fixed capital formation has not grown since 2014.

• All the relative gains in income distribution (market income and after tax and transfer income) have gone to the top 10 percent over the last 30 years.

The textbooks on managing risks and uncertainty highlight two success factors—accommodate challenges (do not make decisions that ignore them) and build capacity to manage risks.

In rolling out 2019 election platform initiatives, the government needs to give priority to initiatives that reduce imbalances.

The Liberal platform proposed about $57 billion in new deficit finance initiatives over four years. While the money was spread over close to 50 initiatives, the majority went to a broad-based tax cut, seniors, families, health care and education. The climate change agenda—the commitment to get to zero net carbon emissions was not costed. Over the next four years, the Liberal commitment was to raise some $25 billion in new revenues or savings through reviews and tax increases on corporations and luxury goods.

Do we need to see all or some of these initiatives in Budget 2020? Maybe less is more and fiscal capacity is saved to help stabilize a potentially unstable economy.

Do we need to see all or some of these initiatives in Budget 2020? Maybe less is more and fiscal capacity is saved to help stabilize a potentially unstable economy.

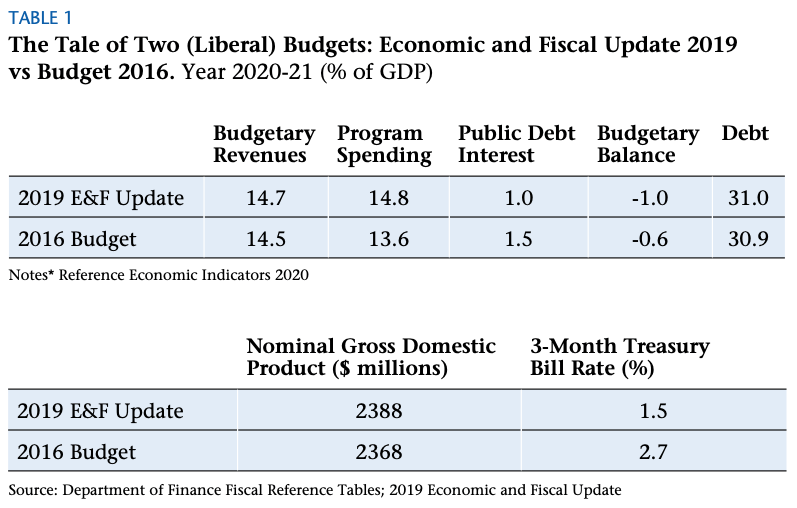

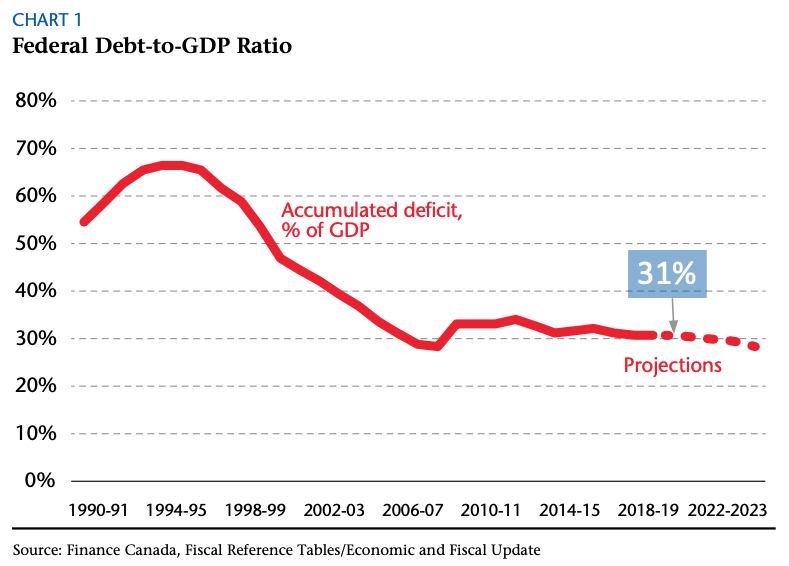

Building trust on fiscal management is a challenge. Having a good track record is indispensable. In the 2015 and 2019 elections, the Liberal fiscal strategy was to run modest deficits and put the federal debt to GDP ratio on a downward path. Table 1 compares fiscal and economic projections for 2020-21 between the Fall 2019 Economic and Fiscal Update and their (first) Budget in 2016.

With respect to deficits and debt, the world has largely unfolded as planned some four years ago. It is a fiscal management achievement that deserves to be noticed. What stands out, however, is that the Liberals have spent the economic dividend from lower than expected interest rates. There is a penchant to increase spending.

With the building of economic imbalances, it is worth considering how much room the government has to introduce new spending initiatives and cut taxes and how to use it. Unusually low interest rates have two upshots: first, governments can carry higher levels of debt without facing a sustainability crunch. Second, monetary policy has less room to maneuver if a recession hits, which means that fiscal policy needs to be able to step up.

Currently, the Liberals’ main fiscal sustainability objective is to keep the debt-to-GDP ratio declining, a goal that will be difficult to demonstrate in Budget 2020 without new savings measures. This target leaves important questions about appropriate planned limits on spending.

Currently, the Liberals’ main fiscal sustainability objective is to keep the debt-to-GDP ratio declining, a goal that will be difficult to demonstrate in Budget 2020 without new savings measures. This target leaves important questions about appropriate planned limits on spending.

To build confidence and credibility, the Liberals could work on creating a more transparent, comprehensive, and clearly defined fiscal planning framework with a focus on long-run economic growth. To strengthen accountability, they could consider targets on spending and the budgetary balance (deficit) in addition to a medium-term debt to GDP rule. To promote intergenerational fairness, they could develop principles on the use of deficit finance.

Contributing Writer Kevin Page is founding President and CEO of the Institute for Fiscal Studies and Democracy at University of Ottawa. He previously served as Canada’s first Parliamentary Budget Officer. He has been joined in preparing this Budget preview by students Kyra Carmichael, Nicholas Liban Dahir, and Hiba Khan.