Brian Mulroney, a Canadian Leader of International Consequence

By Jeremy Kinsman

March 1, 2024

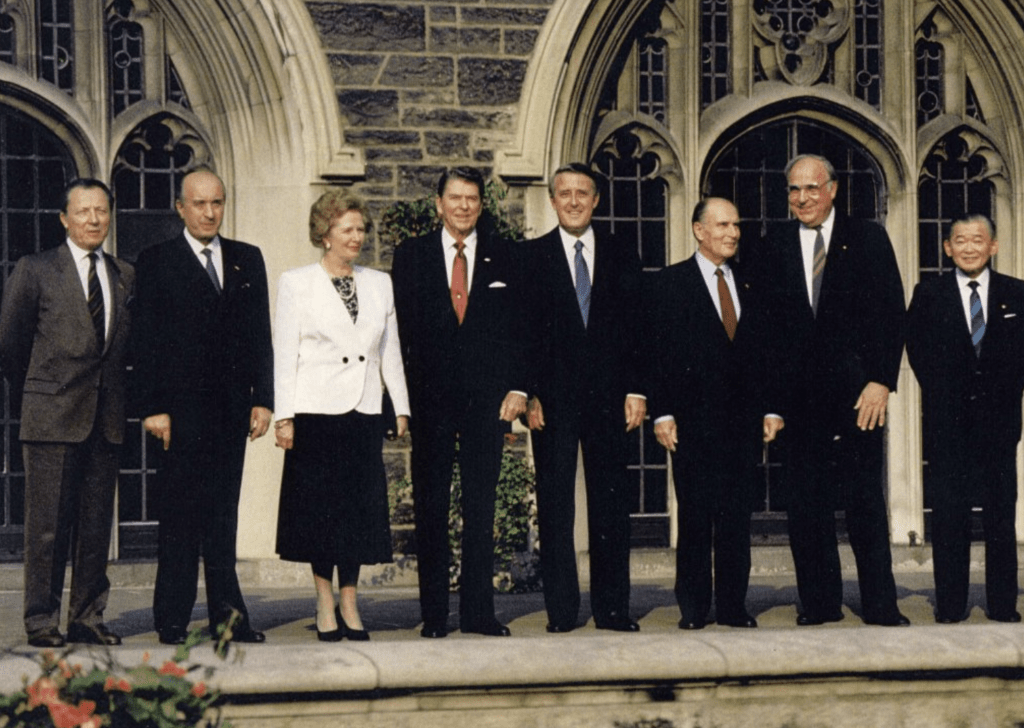

In the hours and days following his death, tributes to Brian Mulroney’s international influence were delivered by many notables, including James Baker, US master of everything in the Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush administrations. The warm Mulroney-Reagan relationship shifted the ground between Canada and the US, though the prime minister’s closest personal international relationship was with the first Bush.

Together, and with such other strong leaders as Margaret Thatcher, Francois Mitterrand, and Helmut Kohl, these leaders shaped a relationship of trust with Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin that ended the Cold War. Yeltsin considered Mulroney the western leader he trusted most during those critical years of challenging change.

On 19 August, 1991, when a putsch by old Soviet communist hard-liners announced that control of the country had been seized from Mikhail Gorbachev, other Western leaders were initially wavering to see how it turned out. Analysts who were Cold War survivors counselled such caution, since we may have had to live with the new regime. When the prime minister got wind of such cautionary advice from the Soviet desk officers in Ottawa, I had a rare call from Mulroney himself. I assured him this was just Cold War muscle memory. He said, “Jeremy, that’s not who we are. This is about principles we believe in.”

Within hours, our Moscow embassy had patched through a call from Brian Mulroney to Boris Yeltsin who was mounting a strong campaign of public resistance (I think he took the call on a cell phone atop that famous tank). The Prime Minster pledged Canada’s total support to Gorbachev (and Yeltsin). Within hours, Canada’s G-7 and NATO partners were pledging the same.

When it came to human rights, there was never any uncertainty from Canada during Mulroney’s time as to “who we are.” As Lucien Bouchard and Jean Charest recalled on Radio-Canada following his passing, Mulroney, as a leader, always did the courageous thing that came from “who we are” and who we could be. As they said, he didn’t do so from political calculation or focus groups, but from principle. As Bouchard observed, “Il avait du coeur.”

This authenticity and Mulroney’s personal warmth and emotional intelligence were the basis of his influence with his international peers. They ensured that Canada punched in world affairs above our weight. It was Mulroney who told Bush in August 1990 after Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait that the US had to get the Security Council to agree to authorize a UN force, and if he called Francois Mitterrand, France would be on board. Bush did, France was, and it all succeeded. Mulroney wasn’t just words —he made sure that Canada was an all-in participant with our largest expeditionary force since the Korean War.

His diplomacy as leader was personal, conveying the strength of his convictions, and the breadth of his contacts. Mulroney had things to say to his peers, and some were harsh when necessary, as on the necessity of crushing apartheid, or committing to global defense of the environment.

I became accustomed to doing press briefings at NATO and G7 summits and on his official visits in Moscow that were standing-room only, because Canadian Prime Minister Mulroney was there and he had something important to say.

His contacts went beyond the reach of his G-7 peers. It was on the evidence of his range of influence and his own experience with Brian Mulroney that President Bush favoured Mulroney to be secretary general of the United Nations, though in the early 90s it was still a non-starter for a NATO member country to assume that role.

Leaders of Commonwealth and Francophone countries knew him personally and he knew them and their issues. Indeed, Francophone leaders, wary of France, looked to him for leadership. Commonwealth leaders, equally wary of the UK, did the same. His nurturing of those relationships as an honest broker echoed his approach to bilateral relations with the US, which saw pragmatic harmony as mutually beneficial.

The Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) was held in Harare, in October 1991, reasserting in “The Harare Declaration” that the organization needed to be defined by commitment to democracy and human rights, including gender equality, and that membership would rely on their acceptance in practice.

At the time, conference chair Robert Mugabe was still formally in favour of those principles, under the beneficent influence of his first wife, Sally, who had been at his side for thirty years. (Sadly, Sally Mugabe died the next year and Mugabe’s commitments to democracy with her.) But in the very restricted leaders’ sessions, the atmosphere was hot from caustic dissent on these Commonwealth principles from such dictatorial egos as Prime Minister Mahathir of Malaysia, President Museveni of Uganda, and President Daniel Arap Moi of Kenya, then a one-party state. They railed against presumptuous interference in their internal affairs. New British Prime Minister John Major and Indian Prime Minister P. V. Narasimha Rao kept a low profile, leaving much of the running in the debate to Mulroney and Australian PM Bob Hawke, supported by Jamaican Michael Manley and others. Mulroney spoke forcefully, always courteously, but firmly, evoking the struggle of absent hero Nelson Mandela, who had been released from South African prison only nine months before.

When the session broke, Kenyan President Moi came over to the Canadian chair to protest. (Moi was under pressure that autumn to re-enable the multiparty democracy his administration resisted.) His attitude was, effectively, “Who do think you are?” He carried a traditional fly-swatter he kept thomping against his thigh as he berated Mulroney. Most politicians would’ve walked away or tried to de-conflict the conversation. Brian Mulroney stared down the Kenyan President, but with exquisite politeness (his usual practice, incidentally), addressing the older man as “Sir,” but asserting his own obligation to speak for values and aspirations that were increasingly those of people, especially young people, everywhere. The Commonwealth needed to show them what it stood for. He urged Arap Moi to consider the merits of taking the lead for justice.

They didn’t part as pals but they separated in mutual respect. The next day, the Kenyan president endorsed the Harare declaration. A month later, he permitted multi-party elections in Kenya, against the fears of his advisors. (In fact, he won, though electoral observers did not award the “fair and free” endorsement.)

I was curious in the next days to see if the prime minister would, in his press encounters, allude to this conversion or to his leadership role in the discussion, or suggest that we leak it. He didn’t. He didn’t have to. It happened and his presence was felt.

I became accustomed to doing press briefings at NATO and G7 summits and on his official visits in Moscow that were standing-room only, because Canadian Prime Minister Mulroney was there and he had something important to say.

His death has been unsettling for those who remember such strengths. While his leadership at home sometimes ran into troubled waters, internationally, he was a rare leader of real beneficial consequence.

Policy Contributing Writer Jeremy Kinsman was appointed Ambassador in Moscow in by Prime Minister Brian Mulroney in 1992, having been Political Director at the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. He went on to be Canada’s Ambassador to Italy and to the European Union, and High Commissioner to the United Kingdom.