Brace Yourselves: The Tests of 2021

Where 2020 was a year of shocks, 2021 will be a year of tests. Tests of international collaboration, of policy innovation, of systemic integrity and of societal resilience. We have experienced the previously unthinkable in so many negative ways recently, that if we can meet the challenges of the next year, our sense of the possible might just take a turn for the better.

Kevin Lynch and Paul Deegan

A year ago, most Canadians had never heard of a novel coronavirus. Yet, COVID-19, a particularly virulent virus, dominated our lives and livelihoods in 2020 and will continue to shape them throughout 2021. Its toll on public health, economies, government finances, businesses, and families will last for decades.

We had been warned. On May 15, 2017, the cover of TIME magazine blared, “WARNING: WE ARE NOT READY FOR THE NEXT PANDEMIC”. A second “black swan” crisis in just two decades points to the need for better contingency planning and greater resiliency built into our core health, financial, and economic systems. We should not forget these lessons as we look ahead. Canadian governments and Canadians face a number of must-tackle challenges in 2021. These will test our capacity for creative, collaborative, longer-term thinking, and whether we can raise our policy game to emerge stronger and more resilient in an uncertain and interconnected post-COVID world.

The first test for all governments is to control the COVID-19 pandemic. Without flattening the COVID curve, the recovery will be planked.

While newly developed vaccines hold the promise of controlling the virus, it is the execution of the vaccination program itself that holds the key to success—delivering a two-dose vaccination to 38 million Canadians, across immense geography and various jurisdictions, and in lockstep with other countries. Canada’s less-than-stellar record to date with widespread rapid testing and contact tracing elicits concern on the execution front. Add to this the fact that the newly developed vaccines are neither licensed for production in Canada nor guaranteed for earliest delivery in the government’s vaccine purchase arrangements, and the execution risks rise.

As Canada’s plans to distribute these vaccines from American, British, and European producers to Canadians are firming up, we are experiencing a significant second wave of the pandemic, leading to renewed lockdowns in various parts of the country and increasing pressures on the health care system. The slower the execution of the vaccination program, the slower the economic recovery and the greater the economic and social costs. We should have been better prepared, particularly after Canada’s experiences with SARS in 2003 and H1N1 in 2009.

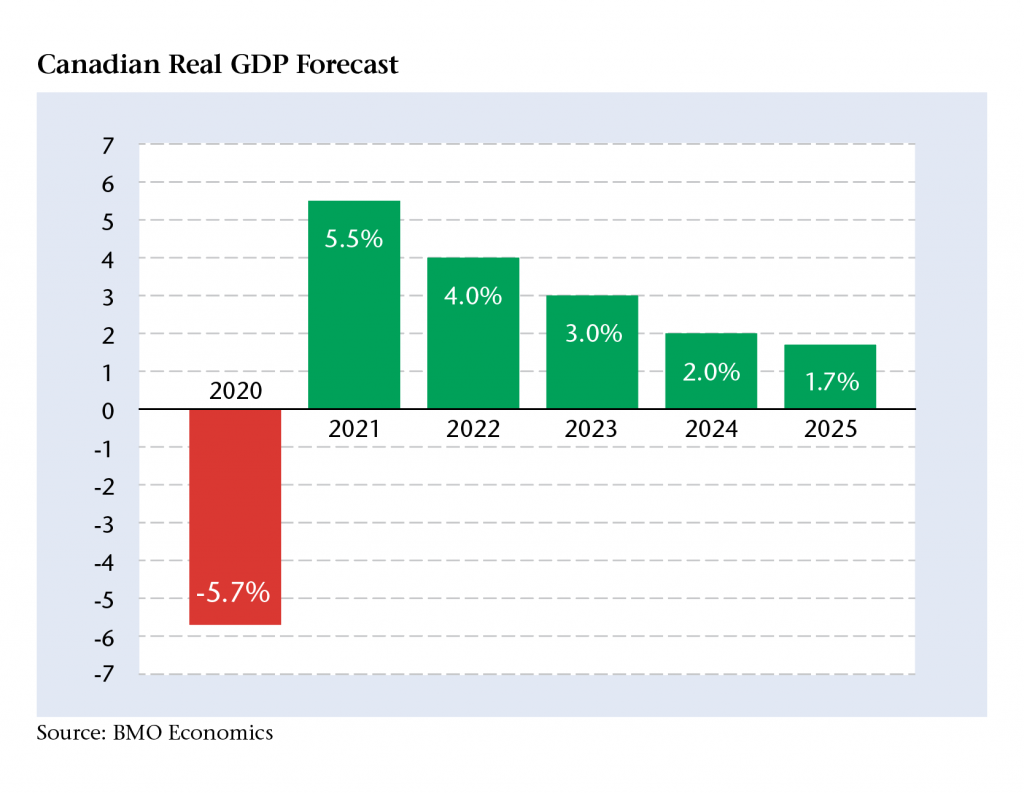

The second challenge is a growth strategy for the recovery and beyond. The economy will not return to pre-pandemic levels until 2022, and that assumes a vaccine-assisted rebound combined with a shift in government spending from income and liquidity support to growth- enhancing measures. Beyond the immediate challenge of recovery, which is to get back to pre-COVID levels, we also face a troubling drop in longer-term real growth to 1.2 percent according to Bank of Canada estimates, due to a wicked combination of poor productivity performance, weak capital investment, slow labour force growth and lasting scarring from the pandemic recession. That implies stagnant per capita incomes, or even worse for segments of the population. As former Senior Deputy Governor Carolyn Wilkins said recently, “Businesses are investing less because of the pandemic, and that puts a lid on how much potential the economy has to grow.”

Rebuilding Canada’s potential growth will require a clear plan to improve our competitiveness, encourage productive investments and create a Canadian global advantage. Governments cannot solve all problems, but they can help create the conditions to make the private sector more successful. We are at one of those pivotal moments.

A third challenge is the glaring absence of a fiscal anchor from the government’s policy playbook. A fiscal anchor is not something that waits for better times—it is something that is a prerequisite for sustained better times. Federal debt will have risen an astounding 75 percent between last year and next year according to the Fall Economic Statement 2020. This debt burden, which future generations will bear, comes at both a cost and a risk.

The debt servicing cost is manageable while interest rates are at abnormally low levels because of the pandemic recession, but they will gradually rise as growth returns. The risk is that international financial markets begin to lose faith in our ability to manage our fiscal affairs—after all, how much confidence should they place on a fiscal projection of a drop in the deficit from nearly $400 billion this year to under $100 billion by 2022 without any fiscal constraints. To avoid this, and its caustic effects on growth and confidence, the government should articulate a credible fiscal anchor for these uncertain times.

A related challenge is fiscal federalism: provincial fiscal situations are not good, some are dire, and all believe that increased federal transfers are in order, particularly since the federal government has loudly argued it has unused fiscal firepower. The health system clearly has to be better prepared for future pandemics, and this will take money, partnerships and surge capacity. And, with the Liberal government signalling new policy ambitions in areas of provincial or shared jurisdiction, the price tags to encourage provincial buy-in will be lofty. This combination of provincial fiscal gaps and federal policy plans will only place more upward pressures on federal transfer spending, and reinforce the need for a fiscal anchor.

There is no question that we need to transition to a low carbon, greener economy. But, as Samantha Gross of the Brookings Institution has argued, “Those pushing to end fossil fuel production now are missing the point that fossil fuels will still be needed for some time in certain sectors.” The reality is that energy is our biggest export earner, and a major source of value-added growth, well-paying jobs and tax revenues. The challenge is how to sustain a robust Canadian energy sector and make real progress on climate change. It is not an “either or” choice, it is about achieving both.

There is no question that we need to transition to a low carbon, greener economy. But, as Samantha Gross of the Brookings Institution has argued, “Those pushing to end fossil fuel production now are missing the point that fossil fuels will still be needed for some time in certain sectors.” The reality is that energy is our biggest export earner, and a major source of value-added growth, well-paying jobs and tax revenues. The challenge is how to sustain a robust Canadian energy sector and make real progress on climate change. It is not an “either or” choice, it is about achieving both.

This is not just an Alberta problem, it is a pan-Canadian issue—both economically and politically. Why can’t we reduce carbon dioxide emissions in the oil sands through the deployment of Generation IV Small Modular Nuclear Reactors to meet the steam and heat requirements of Alberta’s heavy oil industry, which are currently met by carbon intensive fuels? This would dramatically limit greenhouse gas emissions from oil sands operations, allowing time for the province to diversify its economy and become a global clean energy leader. This is where new thinking and a new narrative is so desperately needed. As Gross argues, “Eliminating unpopular energy sources or technologies, like nuclear or carbon capture, from the conversation is short-sighted. Renewable electricity generation alone won’t get us there—this is an all-technologies-on-deck problem.”

Canada-US relations are a challenge that always looms large over Canada’s foreign and trade policy priorities, and never more so than during the chaotic Trump presidency. While the Biden administration will be a welcome change for most Canadians, it will come with unresolved issues—including pipelines, Buy America, softwood lumber tariffs, Huawei involvement in 5G networks and national security exemptions—that will all continue to affect the Canadian economy.

Now is the time to reach out to the Biden administration, which will be struggling in the fraught political aftermath of the election, on how we can work together to solve common issues, not present a list of “asks” and concerns. This could include upgrading NORAD’s 1980s-era North Warning System in the Arctic; ensuring that both countries have an adequate supply of critical goods ranging from personal protective equipment to pharmaceutical compounds; investing in next-generation North American energy grids and clean energy production; expanding environmental co-operation; and engaging China together, with allies, where we have common purpose.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has identified income inequality as an impediment to the recovery in most countries, including Canada. The challenge of inequality has risen significantly during the pandemic, with ongoing social, economic and political impacts. The IMF has highlighted that inequality is not just an income issue, it is an opportunity issue with unequal access to digital skills and broadband, and it is a health issue which the pandemic has laid bare. As Binyamin Applebaum of the New York Times has written, “The distribution of wealth and income has a meaningful influence on the distribution of opportunity, on the mechanics of the business cycle, and on the pace of innovation.”

During the COVID crisis, many lower-wage workers were overrepresented in essential roles in the retail and health care sectors where working remotely is not an option. Women and minorities were overrepresented in service-sector job cuts due to the pandemic. Inequality is becoming as much a blocker to economic growth as it is an unacceptable social reality in advanced western economies. This is a challenge that Canada can lead on, both at home and abroad, but feel- good rhetorical bromides are not a plan.

There are decades where nothing happens and there are weeks where decades happen. This saying seems particularly apt to describe what has transpired during the pandemic. And we will continue to be tested, but the focus will shift from the immediate crisis to the recovery and beyond. The longer-term challenges before us in 2021 will also demand a much more innovative and cooperative approach to policy-making—both at home and with our allies.

Having been caught flat-footed, the questions we need to ask ourselves today are do we have the necessary strategic planning skills within government, the right incentives for private-sector expansion, and the collective will and wisdom to “build back better”?

Contributing Writer Kevin Lynch was formerly Clerk of the Privy Council and Vice Chair of BMO Financial Group.

Contributing Writer Paul Deegan, CEO of Deegan Public Strategies, was a public affairs executive at BMO Financial Group and CN, and served in the Clinton White House.