Why Did We Fail So Badly at Pandemic Communications?

Washington Post

Washington Post

Excerpted from the book Emergency! Quarantine, Evacuation and Back Again

Passamaquoddy Press/2022

Robin V. Sears

June 1, 2022

It is not the fault of the epidemiologists and other public health officials that they are often so poor at effective public communication. As a senior epidemiologist at a major Toronto teaching hospital said with exasperation when I complained about his colleagues’ monotonal, hesitant communications performance: “Look, we are lab rats and data nerds. We use an impenetrable vocabulary and jargon. We hate being asked about the future or for certitude. We deal with the past and ranges of possibility in the future. We live with ambiguity. We have a hard time communicating with colleagues outside our own circle. What did you expect?!”

All of these issues – jargon, data, and ambiguity – are huge impediments to effective communication. Constrained as well by team and institutional loyalty, and tough Canadian privacy laws, public health officials are loath to discuss real people or cases. They are therefore mostly incapable of employing the most effective form of communication: storytelling. Effective storytelling requires character, plot, and an arc of narrative.

Occasionally during the COVID pandemic, one would hear a briefing from one public health officer or a medical expert who cited the experience of a colleague, a patient or a team while protecting their identities. But they were usually somewhat awkward moments made painful to watch given the clear ambivalence of the presenter about propriety. This failure rests on a deeper and more challenging foundation: scientific literacy does not matter. It doesn’t matter to employers, parents, or politicians. There is no penalty for not knowing the difference between astronomy and astrology. Indeed, it’s the type of ignorance that people make self-deprecating jokes about. “I couldn’t tell a telescope from a stethoscope…”

Until a few decades ago, innumeracy did not matter, either, to most of society’s institutions.

Accountants had to count, mathematicians had to equate, engineers had to triangulate, but ordinary folks needed merely to be able to add and subtract – somewhat. Literacy mattered, though. Fail math and your parents would chuckle disapprovingly; fail English, history, or literature and you were more often in trouble. By the 1970s educators, were beginning to focus on how badly math was being taught, and to find new methods of making numeracy respectable; for many, even fun. By this century, educators and governments had begun to turn to technological literacy, but narrowly defined and, until recently, only taught to older students. Perhaps one of the pandemic’s lessons will be a new focus on scientific, evidence-based decision-making by governments and the private sector, and a demand that educators do a better job at teaching scientific literacy.

As a sign of our indifference, there is but one member of Parliament in Canada today with a doctorate and a background in scientific research.

If understanding the role of science does not matter, and without an ability to separate scientific nonsense from good sense, then public health will struggle. Public health is merely a subset of a vast array of science disciplines. Knowing the difference between good data analysis and bad (essential to policymakers and parents) is one of the powerful lessons of this painful period.

Consider how many thousands of lives might have been saved in Italy, France, Spain, and the United Kingdom, if the governments of those states had been competently led by persuasive leaders – not to mention the tragedy to our south

We learned that scientific literacy mattered more in a public health crisis than in any other, the promotion of bleach and electric light administered internally got too much airtime and won too many believers. Like threats of violence to a community by an adversary or a terrorist, pandemics cannot be seen until they start to wreak their havoc.

There are failures on both sides of the science/politics divide. Scientists are loath to get their hands dirty with the sometimes grubby trade-offs of political deal-making. Politicians are leery of scientific truth-telling,especially in a crisis. But these two solitudes need to get over themselves. Policy decision-makers need to be capable of taking tough scientific counsel; scientists need to find ways to build bridges over the chasm that divides them.

These gaps, misunderstandings and professional stovepipes became stunningly clear when this pandemic hit. We did not even recognize the early signals. We were not tuned to the implications of two cases in two nearby places being a potential disaster within days. We were slow to believe, slower to act, and too quick to fall off the public health wagon at our first opportunity.

To persuade citizens of the need to change hygiene behaviour quickly, they must understand the basic principles of public health. The effectiveness of the messaging is based on the communications skills and credibility of the leadership delivering the message. In most places, we had neither a willing audience nor a convincing leadership. As late as April 2021, some governments could still not deliver a clear and succinct message about lockdown rules and changes to them. This led to widespread criticism and confusion.

For most men and women drawn to the complex world of analyzing, predicting and identifying epidemics, the public stage is not a familiar, or in many cases, even a welcome place. People such as Anthony Fauci and Bonnie Henry are outliers and rockstars in their field. They have an ability to communicate powerfully, confidently, and with demonstrated success at persuasion. Perhaps they should be tapped to train some of their peers. Give those who aspire to their level of competence regular professional training, and retraining.

The hiring committee for Canada’s first public officer of health decided that effective public communications skill was a top tier requirement for the role. The man they hired, David Butler-Jones, was a natural storyteller, a lighthearted and effective communicator. Sadly, the same skill set was not required of his successors. His success and that of Dr. Fauci even elicited jealous whispers among many of their colleagues — “showboating” it was called.

For the vast majority of scientists who spend their professional lives in labs with a small team of other scientists, maybe it is not reasonable to try to force them to master the art of media wrangling in front of dozens of journalists and a skeptical public. There is a fear of “professional taint” among too many scientists at being seen to be too political or even too often seen in public.

Why did we not more frequently use respected public figures from other sciences, the arts, sports, entertainment, and even business as validators and reinforcers of essential messaging? Sad to say, most military leaders err on the side of “Because I say so…” as opposed to “Here is why I think this is important to you and your family…” when thrust into public leadership roles. But every country has a small army of professionals in the media, the arts, the academy, and business who live by their skills as storytellers.

One of the realities of crisis management is that you are always going to be asked to make decisions with too little information — or even conflicting information — and too little time

Another basic tenet of communication is the need to choose the best messenger with the best message for a chosen target audience(s). Scientists need to deliver complex science messages. Ministers and political leaders have no credibility in playing scientist. At a minimum, given our embarrassing experience with some public health officers’ ability to appear competent and convincing on stage, let’s ensure that everyone in those key public messenger roles at least receives and gets regular refreshers in the mysteries of moving the minds of fellow residents at times of great fear. To fail to do so, considering the years we have just been through, would at best be thoughtless, and at worst criminally irresponsible.

As a thought experiment, consider how many thousands of lives might have been saved in Italy, France, Spain, and the United Kingdom, if the governments of those states had been competently led by persuasive leaders – not to mention the tragedy to our south. Political leaders who fail as communicators, in a public health crisis, have no excuse for being so unpersuasive, inauthentic, and often simply laughable. Those who point fingers at other governments or blame the cultural practices of one ethnic or religious community, who refuse to take responsibility or offer any apologies for their mistakes, should simply step aside and leave the communications leadership to those who know how to be effective and credible.

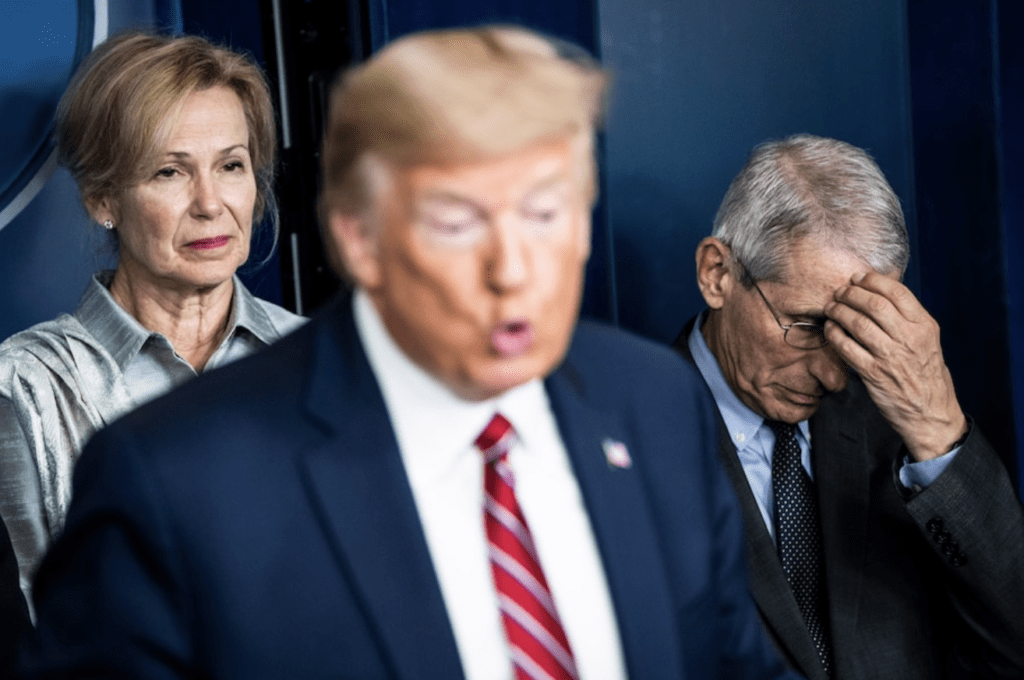

Donald Trump was the worst offender in pandemic crisis communications — just one chapter of his volume of lies, big and small, culminating in the big lie about winning the election of 2020. But too many others approximated his indefensible performance. Dry, monotonal recitation of statistics, foggy lockdown rules, and pleas alternating with veiled threats, were the norm from too many premiers and governors. This is very serious in a public health crisis, as establishing credibility early, and being judged positively on initial crisis messaging is the foundation on which one can build bigger and more difficult steps later. If, like some Canadian premiers and many American governors, you were seen to have been less than transparent, or competent, in the early days, you could never regain the credibility for the much tougher challenges of a yearlong crisis.

One of the realities of crisis management and having the strategic communication skill to maintain community confidence is that you are always going to be asked to make decisions with too little information — or even conflicting information — and too little time. Bureaucrats and medical managers do not excel at this. Risk-averse, trained to minimize potential damage, they must err on the side of too little and too late. The fog of war, in the immortal words of the great German military strategist Carl von Clausewitz, is the inability to execute the best laid plans with the unanticipated, unpredictable interplay of factors on a battlefield no one could claim to have seen in advance. More pithily, if perhaps less immortally, as Mike Tyson put it, “Everybody’s got a plan until they get punched in the face.” If you have ever witnessed the spellbinding and breathtaking risks that a battalion commander needs to take in an active war zone, deciding the fate of his own troops and that of the enemy’s often several times a minute, you would probably thank God you never were asked to play such a leadership role.

If, in a civilian context, you have been privileged to stand beside seasoned fire chiefs as they direct dozens of firefighters in a five-alarm fire that threatens an entire neighbourhood and the lives of their troops, you would be equally eternally grateful that this is not a role you will ever be asked to fill — even more grateful for the skill, courage and audacity of the leaders who do so to serve their communities. These are the parallels to pandemic crisis leadership: rapid response, risk of horrific error, and an ability to instantly recover – not qualities for which doctors, bureaucrats or even many political leaders are famous.

Contributing Writer Robin V. Sears, former national director of the NDP and later Ontario delegate general to Asia, is an independent communications consultant based in Ottawa.