Bonds Away

Douglas Porter

August 4, 2023

There is no summer lull for financial markets in 2023, and certainly not for bonds. Even with a significant relief rally on Friday, the dominant story for this week, and arguably for the past three months, has been the relentless grind higher in long-term yields. To pick but one example, the 30-year Treasury has leapt above 4.2%, up 40 bps from levels just a few short weeks ago, and 125 bps north of last summer. A mild U.S. payroll report for July cooled the fires somewhat, and shorter-term bonds actually finished the week with lower yields. But the bigger picture is the grinding back-up in long-term interest rates, and it’s more than inflation gnawing away—the 10-year U.S. real rate punched above 1.8% this week, the highest since 2009. What’s eating at the bond market?

The Bank of Japan got the ball rolling last week by opening the door for its key 10-year JGB yield to rise as high as 1.0% (from 0.5%). While the BoJ has stepped in to contain yields, they’re still up almost 20 bps from last week to around 0.65%.

Fitch’s downgrade delivered the biggest surprise of the week when it followed S&P’s lead (from 12 years ago) to cut the U.S. credit rating to AA+ from AAA. While many market participants shrugged off the announcement as no big deal, it at the very least refocused attention on the U.S. fiscal situation. And it’s not a good look. As we have relentlessly pointed out, the U.S. is running an enormous $2 trillion deficit (over 8% of GDP) at the peak of the economic cycle—not good, not sustainable.

Compounding the fiscal concerns, supply got into the act as well with a larger-than-expected refunding announcement. And, the Fed continues to busily QT away in the background, pouring more supply into an already very well supplied market.

While nearby inflation concerns actually have not played a big role in the recent bond sell-off, there has been a steady edging up of longer-term inflation expectations in market pricing. The five-year forward five-year breakeven rate has pushed up to around 2.5% which, aside from a brief spike in the spring of 2022, is the highest since 2014, and compares to below 2% prior to the pandemic.

Shorter-term, the steady rise in oil prices in recent weeks, aggravated by Saudi Arabia’s unilateral supply cuts, is pushing up gasoline prices and threatens to undo some of the easy wins in lowering headline inflation. Gasoline could easily turn from being a source of relief to adding to inflation within the next two months. WTI is now above $82, compared with less than $70 just a month ago.

Weirdly absent from this list is the economic data itself. While last week’s resilient Q2 GDP and this week’s ADP report for July job gains played roles in the back-up in yields, the overall tone of the data has been mixed. The U.S. PMIs were both soggy in July; the Fed’s Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey pointed to a further tightening in credit conditions and weak demand for loans; job vacancies are drifting down the mountain; and, auto sales were okay at 16 million units, but still well below pre-COVID trends.

What really saved the day for Treasuries, and arguably equities as well, was the mild employment report. Payrolls came in a bit shy of expectations at 187,000, for the second month in a row, and reversing the trend of the past year. In addition, earlier months were revised lower, and aggregate hours dipped 0.2%. It was by no means a weak report, though, as the unemployment rate pulled back a tick to 3.5%, and wages were a bit hotter than expected at 4.4% y/y. On balance, the report was fully consistent with rising hopes that the economy can indeed achieve something akin to a soft landing, although stocks still played it a bit cool this week as the broader rise in long-term yields overshadowed a sea of earnings releases.

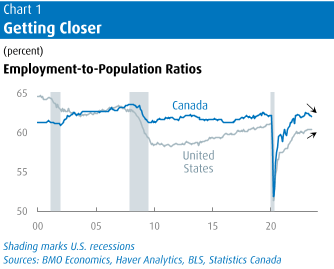

One curious sidebar on the U.S. downgrade was that the U.S. dollar barely budged—by Friday, it was precisely unchanged from a week ago at $1.10 versus the euro. However, it did strengthen somewhat versus the Canadian dollar to $1.332 (75.1 cents), despite firmer oil prices. In contrast to the steady-as-she-goes picture for U.S. jobs, Canada’s employment report was soft as the headline retreated 6,400, the second drop in three months, with a notable 44,700 sag in construction. And while the U.S. employment-to-population ratio is slowly improving, Canada’s has lost ground in the past year, reversing some of its earlier outperformance (Chart 1).

But the real eye-opener was yet another rise in Canada’s unemployment rate to 5.5%. After holding steady at 5.0% from December to April, the jobless rate has now risen for three consecutive months, and is up a concerning 0.6 ppts from a year ago. As we detail in this week’s Focus Feature, that rise is close to ringing alarm bells as a recession indicator. The softening hasn’t been enough to notably cool wages yet—they’re up 5.0% y/y—but it fits well with other indications that conditions are slowing. Early home sales results from the larger cities suggest that the one-two punch of BoC rate hikes in June and July have subdued the housing market again, after it got off the mat in the spring. And, like the U.S., auto sales have risen from last year’s low (up 8% y/y in July), but remain well south of 2019 levels.

Taking these strands together, we are comfortable with our call that the Bank of Canada is done raising interest rates. The recent friendly CPI result of 2.8% (and just 1.7% ex food), and the so-so 0.3% estimated rise in Q2 GDP (about 1.2% annualized) strengthen the case for the Bank to stand aside. The rise in long-term bond yields, insofar as it tightens financial conditions, does some of the work for the Bank. While yields eased heavily after the employment reports, 10s still ended well above 3.5%, and temporarily pushed above 3.7% for the first time in more than a decade. To put that in perspective, this is more than 200 bps north of levels prevailing prior to the pandemic. The bottom-line message from bonds is that even with clear signs that the economy is losing momentum—especially in the job market—sticky inflation and firm wage growth mean higher for longer.

You know the world has changed when one of the first reactions to the announcement of six Taylor Swift concerts in Toronto is: “What will this do for the local economy?” Refusing to get drawn into this pop-economics game, we will studiously refuse to note that ticket sales alone will probably run well into nine-figure terrain. And we won’t mention that local hotel and restaurant demand will get pumped up, possibly aggravating the November 2024 CPI result (see: Beyonce/Sweden). A bit more seriously, the Blue Jays often play to crowds of 40,000 or more for days in a row—albeit at a lower ticket price—so let’s not get carried away. Still, the presumably ferocious demand that the ducats will garner is a signal that the consumer is still very well armed and dangerous to the inflation outlook.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.