Beyond the Shutdown: The Prognosis for a Post-Pandemic Recovery

While there are aspects of this pandemic recession that echo the wreckage of the 2008-09 global financial crisis, the differences, including the uncertainty of having the pace of containing its human and economic damage susceptible to the whims of both a virus and unpredictable policies in certain countries, are crucial. Outgoing BMO Financial Group Vice Chair Kevin Lynch lays out the possibilities for a recovery.

Kevin Lynch

For those who managed companies, steered financial institutions and helped run governments during the global financial crisis of just over a decade ago, it is hard to imagine a more challenging time, but we are in the midst of one now. As the new managing director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Kristalina Georgieva, noted without hyperbole at the first-ever global virtual meeting of the venerable institution, “this is a crisis like no other”. And, as the political scientist Robert Kaplan once observed, “crises put history on fast forward.”

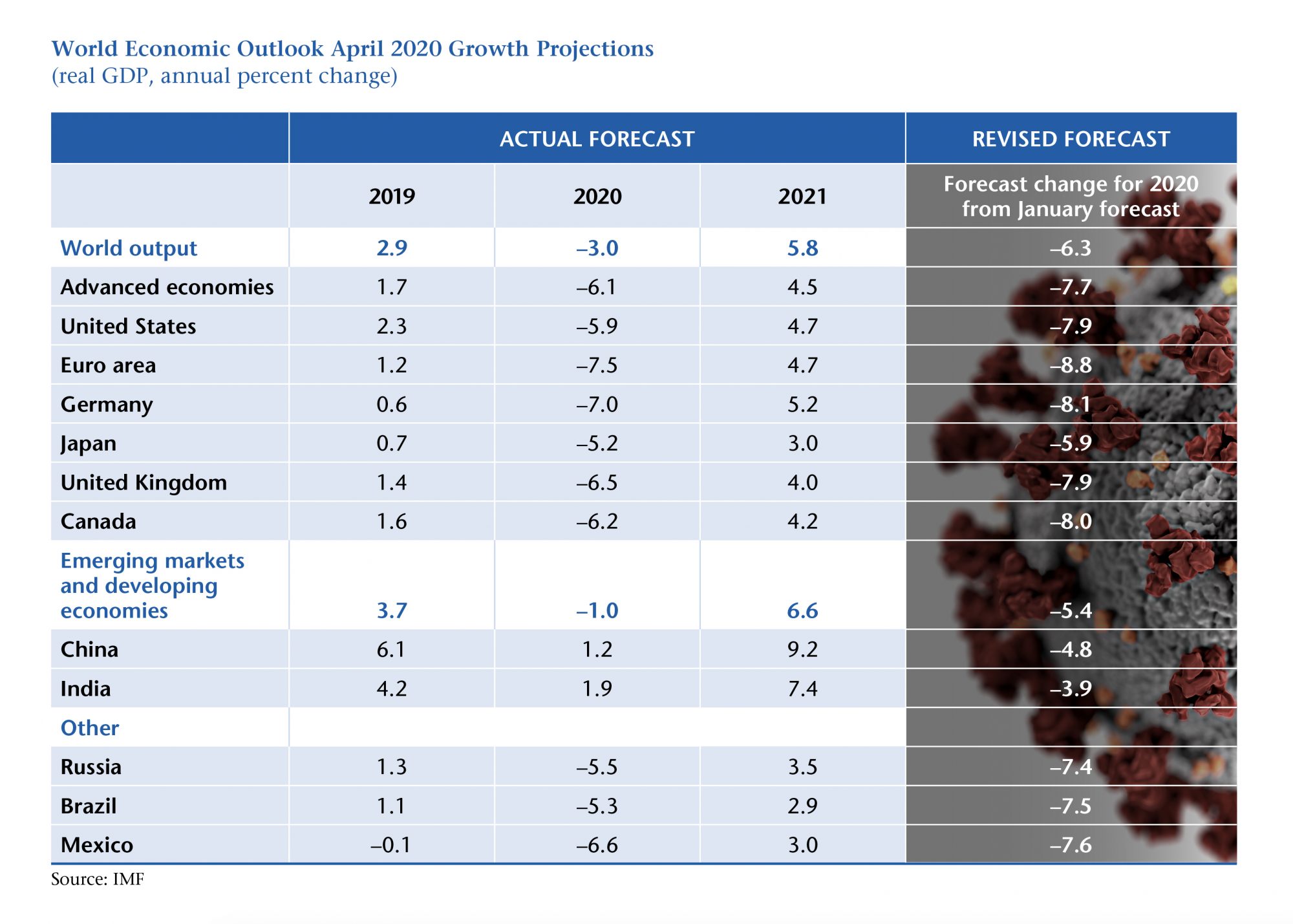

Context is helpful in these circumstances. First, the COVID-19 global recession is significantly worse than the global financial crisis, which severely traumatized Western economies. Global growth in 2009 declined by -0.1 percent whereas IMF estimates of the COVID-19 recession for 2020 are for a fall of -3 percent in global growth. This recession will be the worst since the Great Depression.

Second, this is the first truly global recession since the 1930s, unlike 2009 when advanced economies bore the brunt of the downturn while countries like China and India maintained growth of roughly 8 percent and developing countries overall experienced positive growth. This year, China and India will barely grow and developing countries overall will experience negative growth.

And third, with such volatility in economic statistics, it is important not to confuse growth rates and levels of economic activity: simply put, recovery does not mean recovered. For example, the IMF forecasts growth in the advanced economies to rebound 4.5 percent next year, which sounds robust, but after a 6 percent decline this year this will still leave levels of economic activity in 2021 some 2 percent below 2019, and even further below (5-6 percent) where they would have been in the absence of the pandemic.

At the end of 2019, global debt across all sectors was a whopping $255 trillion, or 322 percent of global GDP. This mountain of debt was $87 trillion higher than at the onset of the 2008-2009 global financial crisis.

Governments have accounted for the lion’s share of this increase in indebtedness since 2007, followed by non-financial corporate debt and then households, with financial institutions being the virtuous exception. Emerging markets account for almost a third of this total global debt and, outside of China, there is significant foreign currency exposure to this debt, which is problematic at a time of widespread flight to safety among currencies.

The global debt mountain is about to get much higher. With massive new stimulus programs coming onstream and the worst of the downturn expected to hit in the second quarter, government debt will soar over the remainder of 2020 and into 2021. As a result, the IMF expects a sharp upward trajectory in global debt-to-GDP ratios, with long lasting implications.

Prior to the pandemic, Canada stood out globally for a highly indebted household sector and high nonfinancial corporate debt-to-GDP ratios but with a relatively low government net debt-to-GDP compared to other G20 countries. Large and lasting increases in Canadian government, central bank and private sector debt will be a consequence of measures to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic and recession. Once the recovery is firmly underway, governments (and firms) will need determined strategies to address this surge in debt in order to protect longer-term growth, competitiveness and living standards.

Economic forecasts typically have a number of core underlying assumptions, usually about monetary and fiscal policy, perhaps commodity prices, sometimes geopolitics affecting confidence, and recently U.S. trade and tariff actions. Never before have global economic forecasts confronted today’s range of unknowns and the intersection of a public health crisis and an economic crisis.

In this environment, forecasting must include epidemiological modelling on the effectiveness of COVID-19 containment measures such as social distancing, travel bans and curtailment of non-essential business, estimates of the timing of the development of new therapeutics and vaccines and, finally, projections on when and how the shut-downs will be lifted. In addition, forecasters have to come to a behavioural view on how lingering health concerns of citizens may alter their normal patterns of working, buying, saving and leisure.

Drawing on this analysis in developing its baseline forecast, the IMF assumes that the shutdowns result in the loss of up to 8 percent of working days in affected countries, that the pandemic fades in the second half of the year as the result of containment measures and shutdowns are significantly unwound by the end of the second quarter, that governments protect lives through investments into public health systems and livelihoods through income support to households and liquidity support to firms, that stimulus measures targeted to rapid recovery are implemented when the shutdowns unwind, and that adequate monetary stimulus and support to financial markets are provided.

The key risk to this forecast is non-economic: namely, the duration and intensity of the pandemic. Michael Osterholm, a leading researcher in the field, has cautioned that pandemics typically come in waves and the ultimate public health response is not social distancing but a vaccine and effective therapeutics which could be up to 18 months away. The alternative scenarios considered by the IMF reflect these cautions.

Globally, after an expansion of 2.9 percent last year, most forecasters as recently as

January expected relatively smooth growth for the world economy in 2020. How quickly things can change.

The revised world economic outlook of the IMF suggests the global economy will sharply contract this year, by some –3 percent, before recovering at a 5.8 percent pace next year. In this global forecast (see Table 1), the U.S. economy declines by –5.9 percent in 2020, Japan by slightly less, Canada and Britain by slightly more and the Euro area by more still. China ekes out small positive growth (1.2 percent) as does India, but overall, the emerging/developing world contracts. Not surprisingly, world trade volumes tumble by double digits (11 percent). For 2021, there is a recovery forecast in the range of 4-4 ½ percent for advanced economies and somewhat stronger for emerging/developing markets.

For Canada, the forecast projection is a dramatic decline of –6.2 percent in growth this year. Underlying this is a huge decline in economic activity during the first half of this year followed by a fairly sharp rebound from these historic lows in the second half. For 2021, a recovery in growth of 4.2 percent is projected but this still leaves activity levels next year below those of 2019. Recent Canadian private sector forecasts are in the same ballpark—RBC projects a decline in growth of –5 percent, BMO forecasts –4.5 percent and TD estimates a –4.2 percent—and all stress these are moving targets given the uncertainty surrounding the path of the pandemic.

Underscoring this uncertainty, the Bank of Canada stated in its recent Monetary Policy Report that “it is more appropriate to consider a range of possible outcomes, rather than one base-case projection.” In one Bank scenario, very much mirroring the IMF baseline forecast, Canada experiences a recession in 2020 that is abrupt and deep but relatively short-lived, with a robust rebound in growth, particularly if oil prices firm. A second scenario, characterized by the pandemic and shutdowns lasting longer, loss of productive capacity due to bankruptcies and lingering low oil prices, would see a deeper and longer recession, a less robust recovery and longer-term structural damage to the economy.

While the immediate priorities for all countries are slowing the spread of the coronavirus among their populations and providing liquidity and income support to firms and households during these unprecedented shutdowns, there are other policy matters that we ignore at our peril.

The first is the importance of international coordination since the pandemic is, by definition, global and the resulting economic recession is also pervasively global, something we have not experienced since the 1930s. As former British Chancellor of Exchequer Gordon Brown eloquently set out in The Guardian, unless we tackle the pandemic with a coordinated global approach utilizing the G20 and the WHO, we risk second and third waves of the virus rolling around the world. And unless we respond to the recession in developing economies through G20 and IMF leadership, we run the risk of an emerging-markets sovereign debt crisis washing into international capital markets.

The second is what will happen to global supply chains, and the likelihood that companies will be increasingly required, by markets or regulators, to map out their supply chains, accompanied by pressures for “re-localization” beginning with healthcare supply chains. Third, moves towards greater corporate concentration may be a structural consequence of a deep recession and a shift to more online commerce. The fourth is inequality, which was a concern in most countries before the pandemic and the recession, and we now face the additional risk of “COVID-19 inequality” with respect to economic and health impacts during the crisis.

And finally, the general theme with respect to policy at these virtual meetings of the Bretton Woods institutions was “we need to do what we need to do.” There was widespread praise for the actions of central banks and a generally supportive view of fiscal actions to date. But, as was frequently stressed, healthcare systems are as critical as macroeconomic policy in a pandemic-induced recession. And here, concerns were raised about the ability of countries to effectively unwind shutdowns and restart economies without significantly allaying public concerns of contagion and personal fears of contracting the virus as work resumes.

Contributing Writer Kevin Lynch, former Clerk of the Privy Council, is retiring as Vice Chair of BMO Financial Group.