Beyond Realism: Canada and America’s Trumpian Discontent

As the United States copes with the domestic and international consequences of the manufactured commotions of Donald Trump’s presidency, Canada is doing its own adapting to the unprecedented nature of the current bilateral dynamic. Former American diplomat Sarah Goldfeder delivers a notably unvarnished assessment of the relationship heading into a new decade.

Sarah Goldfeder

The relationship with the United States has never been simple for Canada. From the beginning, Americans have pushed and prodded Canadians to act in ways that, while undeniably in the national interest of the United States, are not always in the best interest of Canada.

As the larger partner in population, economy, and military power, the United States, it could be argued, has the upper hand. That said, Canada has often benefitted from the asymmetry. But with the clouds of a great power rivalry and a softening global economy promising a darker decade in front of us, how does Canada manage this relationship moving forward?

American Domestic Politics:

Americans are not global thinkers. From the beginning, we have been focused inward, proudly mercantilist and isolationist. It took the horrors of World War II for us to recognize our shared destinies and assume a mantle of responsibility for global security and prosperity. While Americans reluctantly took on a role of global leadership and most were proud of what we could bring to the table, this shift was not without controversy both at home and abroad. Many would argue that it is no small miracle that the post-WWII international rules-based order has sustained as long as it has.

Meanwhile, at home, for two generations, Americans have watched their centres of industry crumble. Both large and mid-sized cities have suffered—Detroit, Buffalo, Cleveland, Youngstown. And yet, at the same time, hubs of emerging technologies are thriving—Plano, Austin, Irvine, San Francisco, Seattle. The gap between haves and have-nots is not just increasing, the factors that influence an individual’s likelihood of being in one or the other of those groups are hardening. The result is a deep suspicion of Americans by Americans, not to mention a gulf in the commitment to the role the U.S. plays on the world stage.

Are Americans concerned about how the rest of world perceives them? Not really. Only when it means that individuals or groups are out to do us harm. Our core values are rooted in libertarianism, meaning that we don’t much care about what goes on beyond our borders as long as it doesn’t encroach on our way of life. But that has changed in the last generation—since September 11th, into less of a “live and let live” mentality and more of a fortress America.

While, since the election of Donald Trump, the U.S. has hovered with one foot in the international community and one foot out, the rest of the world endures the churn of American domestic politics. At the moment, those politics are particularly disruptive to our foreign and trade policy and undermining the international and multilateral engagements we have maintained since the mid-20th century. As we barrel along into the 2020 election, the rest of the world holds its collective breath, waiting to see what new manufactured commotion will drown out the best interests of the international rules-based order.

The Risks for Canada:

Canada often cites its special relationship with the United States. And for Canada, that relationship is paramount. But the United States has always maintained multiple special relationships, each one more special than the others. The result is that Canada’s reliability as a partner and ally is often taken for granted. But that is no small part of the intrinsic value of Canada to the United States—that it acts predictably in the best interests of North America, which usually translates into being a reliable partner. We know when Canada will push back, what it will push back on, and what we have to do to eventually gain their support. It’s a predictable relationship—and that is what makes it special.

The past three years of the Trump administration have been far less predictable than either side is accustomed to. Beginning with the newly elected president’s rejection of the Trans-Pacific Partnership and declaration that the North American Free Trade Agreement would be re-opened and re-negotiated in order to get the United States a better deal, but not stopping there. The deployment of the 1962 Trade Expansion Act’s Section 232 national security tariffs on steel and aluminum created a level of economic angst that frayed the nerves of investors, industry, and politicians as well as government officials. The U.S. trade war with China has disrupted supply chains continentally as well as globally. Continued threats of future 232 national security tariffs against automobiles, uranium, and other commodities continue to undermine investor confidence.

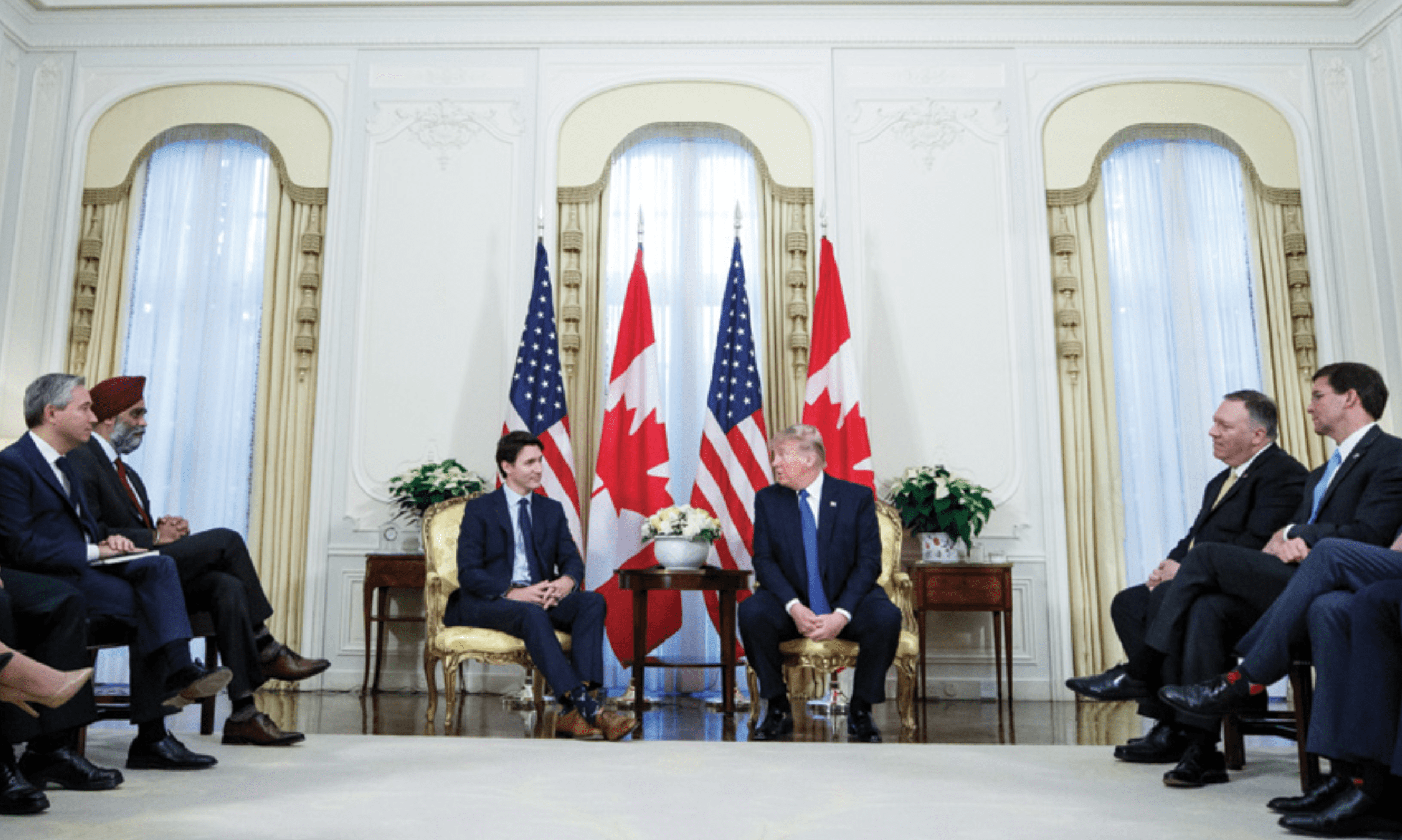

Arguably, any Canadian government would have been ill-suited to manage Donald Trump. Despite the obvious inconsistencies in values and approach, the Trudeau team has done as well or better than any other rules-based, market-based, democratic government in the world. Despite some missteps and presidential twitter-tantrums, the relationship between the two countries appears to have endured in fine fashion. That said, there are still some areas where Canada is at risk.

Trade:

Geography is destiny. Canada has lived this truth through the years, but most notably perhaps, these past three years. Since the renegotiation of NAFTA was announced, the focus of the Canadian corporate world has been on holding the North American market together. While the new and improved NAFTA 2.0 has been signed by all three partners, it has yet to be ratified. The U.S remains in the throes of some of the most partisan political fights in its history and the chances that this renegotiated renegotiation falls flat in the Senate persist.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi made a calculated political decision to announce both the impeachment charges and the agreement on the trade deal on the same day. It mollified her caucus and provided “purple district” members of Congress some good news to soften the blow of impeachment. But the Senate does not share her political concerns—only one third of the Senate is up for re-election in 2020. That one third includes Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and Trump supporter Lindsey Graham. They may choose to punish Pelosi for her timing by ragging the puck on the trade agreement and blaming impeachment for the delay.

All that said, agreements mean nothing if one partner is not acting in good faith. President Trump has proven repeatedly that if he wants more tariffs, he will go after more tariffs and international norms and rules are meaningless. He has also used Twitter to impact business and international trade in unreasonable fashion—something that no trade deal will mitigate.

Simply put, the uncertainty of American trade actions will persist for the immediate future. Meanwhile, Canada continues to suffer from punitive trade actions by China that are political in nature. Expectations that the American president could be helpful with China have so far come up short, and Canada should expect that trend to continue.

Politics:

The Prime Minister’s comments about Donald Trump’s behaviour during a reception for NATO leaders in December became a viral sensation. In the rest of the world, the story was that world leaders also see how rude and boorish the U.S. president can be, but in Canada, the story was politicized as another lapse in judgment by a naïve Prime Minister.

The former is the right story. President Trump showed no respect or courtesy for the other 28 NATO leaders and has appeared to have missed the briefing note where the consensus model for NATO was explained.

Canada Needs More Canada:

Canada just emerged from what is generally thought to be one of the nastiest election campaigns in its history. The divisiveness that characterized 2019 is often thought of as an American export. Regardless of origin, it is toxic. The Westminster system as it is practised in Canada might be the antidote, with the strong minority Liberal government required to work collaboratively with other parties in order to move legislation.

The incumbent Liberals recalibrated over the past four years in order to both manage and minimize the relationship between Canada and the United States. The further divided America becomes, the more Canada moves closer to other allies. The Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement with the European Union and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership both facilitate trade diversification and the cultivation of new strategic partnerships.

Canada’s global value is far more than neighbour to the United States, and as it participates in reform of the World Trade Organization and re-fortifies itself in other multilateral fora, the predictable support that Americans have taken for granted will be embraced by others.

As politicians headed back to their ridings for the holidays, fresh on the heels of a revised NAFTA and with their partner heading into a grueling impeachment battle, Canadians should have felt confident. Their government believes it still works for them. That’s something Americans no longer take for granted, but that quiet Canadian certainty will do the world good.

Contributing Writer Sarah Goldfeder, a principal with the Earnscliffe Strategy Group in Ottawa, has served as a special assistant to two former U.S. ambassadors to Canada and was previously a career officer at the U.S. State Department.