Being Back: Foreign Policy as a Campaign Issue

When Justin Trudeau summed up his foreign policy in 2015 with the message to the world that Canada was back, the world—including the players who didn’t like it or didn’t care—knew what he meant. Since then, he’s been tweet-targeted by Donald Trump, sealed a major trade agreement with Europe and faces a crisis with China. Longtime senior diplomat Jeremy Kinsman looks at the politics of foreign policy four years later.

Jeremy Kinsman

Foreign policy rarely figures as a driving issue in Canadian elections. But in 2019, Canada’s place in the world and international stability itself are severely challenged, in large part because of the disruptive actions of the world’s most powerful country—and historically our most important ally—next door. However, don’t expect leaders to prioritize foreign policy in the campaign. (At this writing, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has not yet accepted an invitation for the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy debate scheduled for Oct. 1).

Campaigning tends to be about what strategists call pocketbook or kitchen-table issues and always leadership, but rarely geopolitics. The emphasis is on communications and leaders’ images, not substance. Trudeau won’t get a free ride on foreign policy in the campaign but isn’t under much pressure either.

Canadian political parties have basically shared a postwar internationalist consensus to support effective multilateral rules-based cooperation whenever possible. It’s always been seen as an essential hedge against over-dependence on the United States, whose primordial importance to Canada is accepted, but whose influence and methods are not always benign. To the extent that issues of sovereignty and national identity have occasionally surged as electoral factors, it has almost always been to do with the U.S., pro or con.

In 1963, Conservative Prime Minister John Diefenbaker’s opposition to accepting the basing of U.S. nuclear-tipped Bomarc anti-aircraft missiles on Canadian soil was a factor in the defeat of his minority Progressive Conservative government. In 1988, John Turner made Liberal opposition to the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement the “fight of his life.” The Liberals were outflanked by the Mulroney government’s support for cultural industries, which neutralized the argument that our national identity was threatened by what was then the Canada-U.S. Trade Agreement.

Indirectly, the popularity or unpopularity in Canada of a U.S. president can lift or hurt prime ministers seeking re-election. Among the unpopular, Canadians loathed Richard Nixon, whose dislike of Pierre Trudeau was a political asset at home. Trudeau was also generally applauded for keeping Canada out of Lyndon Johnson’s Vietnam War, as was Jean Chrétien over George W. Bush’s war in Iraq. Personal compatibility worked electorally for prime ministers who were pals with presidents popular in Canada—Pierre Trudeau with Jimmy Carter, Chrétien with Bill Clinton. Canadian public opinion had, since 1980, been cool to Ronald Reagan’s conservative and hawkish rhetoric, but by 1988 had warmed to the man himself and viewed his affection for Mulroney as a benefit to Canada.

But incompatibility with Barack Obama—who was wildly popular in Canada—worked against Stephen Harper’s re-election in 2015. In his come-from-behind campaign, Trudeau was happy to celebrate Obama’s like-minded liberal internationalism. Once in office, Trudeau affirmed strengthened bilateralism while also declaring he would ensure that “Canada’s back” as a multilateral player. For Obama’s final year, it looked great.

Unfortunately, Donald Trump’s election in 2016 upended the assumptions on both counts. In Canada, Trump is the least popular U.S. president ever. No one running for national office here would dare support his style, apparent values, or the substance of his actions, and expect to win.

On the other hand, the temptation to run a populist Canadian campaign against Trump is dampened by the cautionary principle that Canadians still expect their own leader to be able to maintain a civil and fair transactional relationship with the powerful U.S. leader, which in effect exempts Canada from his impulsive vindictiveness. Once he got past the unprecedented irritant of Trump’s tweeted insults after the Charlevoix G-7 (calling his Canadian host “weak and dishonest”) the prime minister belatedly began to explicitly dissociate himself and Canadians from the president’s offensive assertions (as opposed to saying it’s “not my job to opine” on what the U.S. President says).

On the overarching Canada-U.S. issue—the re-negotiation of NAFTA—Trudeau pushed back calmly on Trump’s repeated lies. Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland led an outstanding negotiating and political outreach effort. The revised NAFTA agreement is more of a defensive save than the kind of groundbreaking win/win outcome that describes the far-reaching Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) with the EU. But in light of the magnitude of Canadian economic stakes with the U.S., it was essential to close a deal, however modest. Because Democrats are so anxious to find arguments against Trump, it may not win congressional approval, but it at least won’t be an electoral vulnerability for Trudeau.

Still, it is now commonplace to assert that the world is today a meaner and more dangerous place. Trump’s “America first” approach to foreign relations, his disdain for both multilateral cooperation and America’s affinity for customary democratic allies have been globally disruptive and run against Canadian values and international interests.

Does this open a perception of difference between Trudeau and Andrew Scheer, whose Conservative base is more receptive to the Washington security community’s call for traditional U.S. allies to get into line? For some, the world’s current disruption and danger argue Canada should indeed be sure that America “has our back.”

In light of Trump’s caprice and mendacity in his approach to Canada since 2016, and given that he is the cause of much of the global disruption, the notion of giving the U.S. our back seems to most Canadians to be somewhere between darkly hilarious and suicidal.

The Liberals will instead pump for their dual approach of strengthening the rules-based international order, including the World Trade Organization (WTO) and its role arbitrating trade disputes and contesting unilateral protectionism à la Trump, (and where Canada is doing very useful reform work), while staying civil enough with the White House to minimize further disruption across our own border.

How will the campaign confront the overriding question of our era—the rivalry between a receding, more inward and defensive, U.S., and a risen, expansionist China? Though the U.S. may be suspected of trying to contain China’s challenge to U.S. supremacy, there is a U.S. political consensus that over twenty years China abused the rules on trade and intellectual property on its way to its current swagger.

Trump launched a trade war with China, via unilateral tariff hikes, that widened to a technology war and even a currency war. Former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers terms Trump’s demands of China more of a “shopping list” of U.S. goods from key 2020 states than serious trade policy, amounting to politically-motivated protectionism. The negative implications for the U.S. economy, which will take a big hit from rising costs, have diminished market confidence around the world, slowed global growth, and even threatened a recession.

Given that the U.S. and China are Canada’s top two trading partners, and that the fraught situation exposes Canadian interests to unintended negative consequences, you would think the trilateral dynamic would be debated in this election campaign.

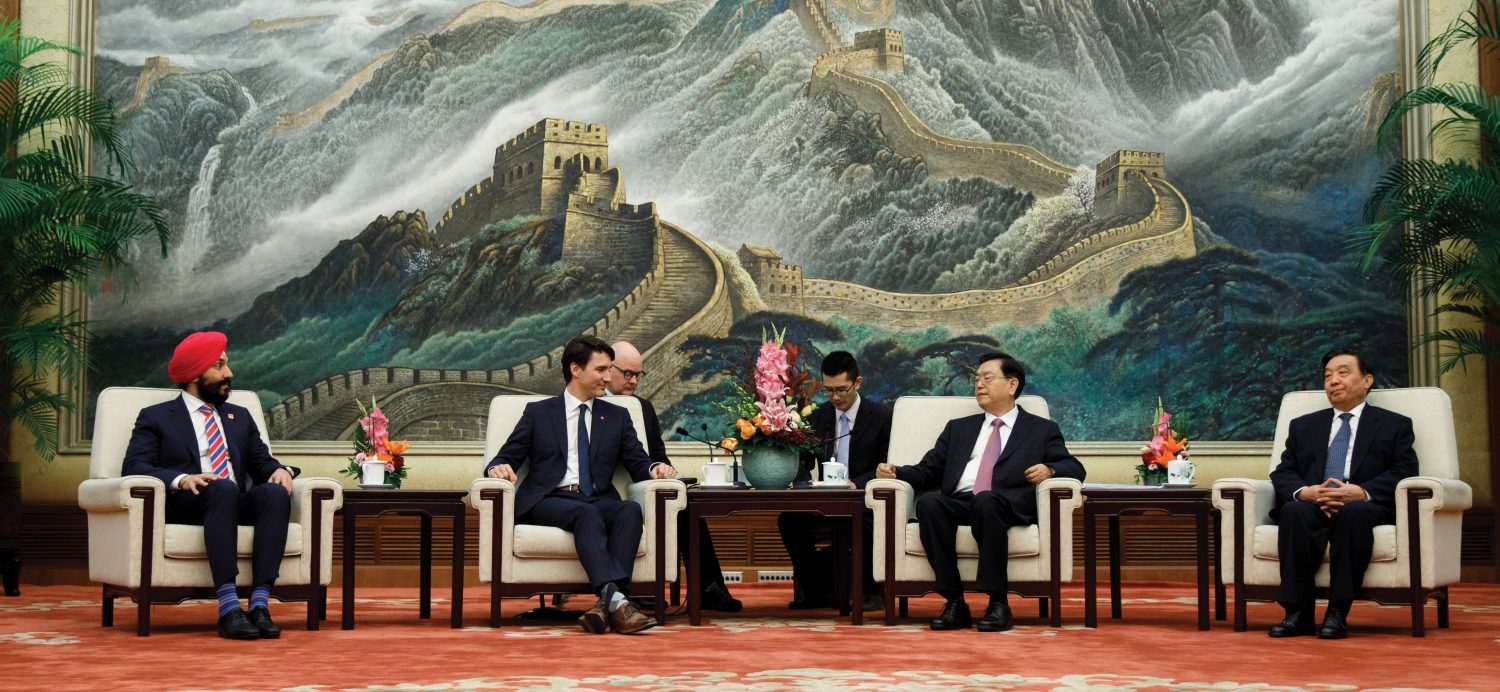

But Canada has its own crisis with China, triggered by the December arrest at Vancouver airport of Huawei Executive Meng Wanzhou , on behalf of U.S. authorities who seek her extradition to stand trial for fraud charges of encouraging evasion of U.S. sanctions on Iran.

China swiftly retaliated for what they consider a hostile act in support of U.S. antagonism to Huawei by arresting two Canadians in China, creating a hostage situation. U.S. authorities seem indisposed to dropping the extradition request. China upped the ante by closing imports of Canadian canola, beef, and pork.

In the event, Canadian judicial authorities may indeed find that under the terms of the bilateral treaty that Meng Wanzhou did not commit what would be a crime in Canada subject to a year’s imprisonment and release her, enabling a solution. But this is unlikely to emerge before the election.

In the meantime, the hostage situation looms over the campaign. Whatever one thinks of the handling by the government of the initial U.S. request, the over-the-top Chinese reprisals have hardened Canadian political and public opinion, and discouraged debate in public. Conservatives deride clumsily triangulated comments from the former ambassador to China that Trudeau hired and fired, John McCallum, that the Tories will be tougher on Beijing if elected, and indeed call on the government to renounce their “naive” wish over the years for a Canada-China partnership. The Liberals will counter that Canada must succeed economically in China, but will not bend before an authoritarian regime that is increasingly under negative international scrutiny and pressure over protests in Hong Kong and brutal repression of its Uighur minority.

On the broader issue of the government’s international relations, Scheer did give a June speech calling them “disastrous,” citing various episodes in which image prevailed over substance with embarrassing consequences—the dress-up jaunt to India, lecturing the Chinese on the role of women, ego-stiffing our partners at the TPP Summit, the Charlevoix G-7 fiasco, but Trudeau has handled himself better recently.

Freeland has been a voice of some significance whose global network from her tenure as a senior editor at both the Financial Times and Thomson–Reuters has served her well. To the extent the U.S. and China files and defence of multilateralism enable her to do anything else, she has been brave on human rights, especially on Saudi Arabia’s strong-arming of dissident women. Some business-oriented Conservatives (and others) seethe about the commercial costs, but after the regime’s murder of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi, it’s a political non-starter. Freeland’s leadership on the Venezuela issue is also positive, even if concerted pressure on the Maduro government isn’t having much effect. A deepening of the Hong Kong crisis and its impact on the 300,000 Canadians there would test human rights commitments.

Trudeau and especially Freeland have been discussing with democratic partners the creation of an informal coalition to defend and reform multilateralism and inclusive democracy. The necessity to strengthen the rules-based international order is a message Trudeau understands and communicates effectively. If our purpose is to be seen as “a useful country,” he serves it well enough (though very probably not enough to enable us to edge out impressively useful Ireland and Norway for a UN Security Council seat in 2020).

Trudeau’s democratic peers abroad are all worried about a backlash over immigration. Canada’s positive integration experience is one they welcome referring to, though he has to avoid sounding preachy to countries whose geography is more challenging than Canada’s from a migration standpoint.

Trudeau hasn’t become the leader of the democratic world but he is welcomed as a like-minded partner of confidence by international peers including Angela Merkel, Emmanuel Macron, Jacinda Ardern and others. They like him; he has influence.

Trudeau has the advantage of experience in the job and a record on the big files of defending Canadian values as well as interests. At a time when Trump’s behaviour has crystallized those values in the minds of voters, that’s probably good enough for most Canadians at least as far as foreign policy is concerned.

Policy Magazine contributing writer Jeremy Kinsman is a former Canadian ambassador to Russia, the UK and the EU. He is affiliated with University of California, Berkeley, and is a distinguished fellow of the Canadian International Council.