At the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, an Imbalance of Strategy

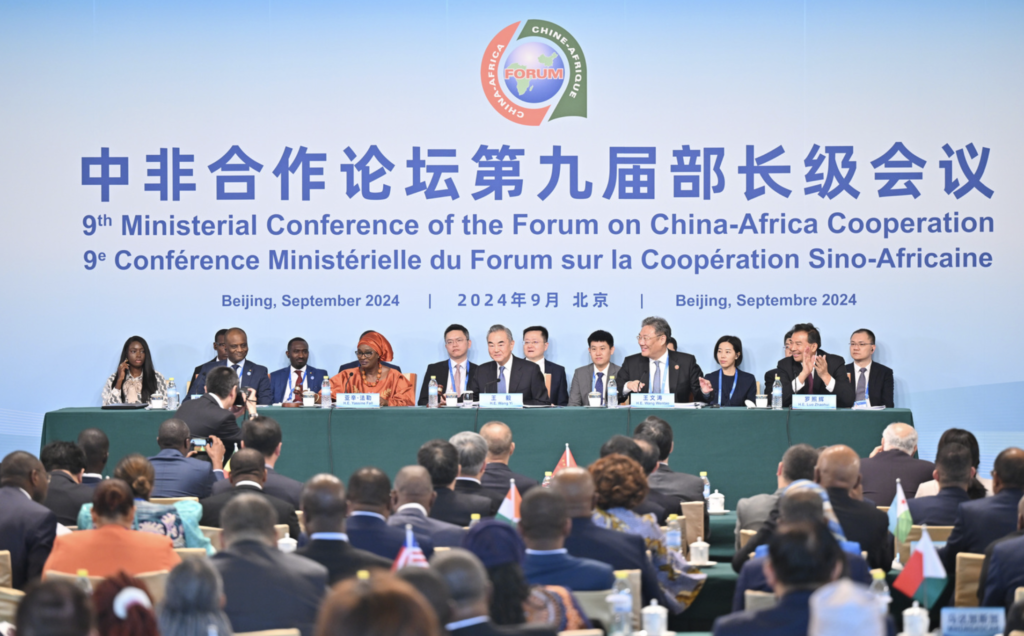

The September 3 ministerial meeting ahead of the 2024 FOCAC/China Daily X

The September 3 ministerial meeting ahead of the 2024 FOCAC/China Daily X

By Bhaso Ndzendze

September 4, 2024

The ninth Forum on China-Africa Cooperation begins today under the theme of “Joining hands to advance modernization and build a high-level China-Africa community with a shared future”. But how shared can that future be between the Asian economic giant and Africa?

The eight summits since 2000 have not resulted in mutual gain, particularly in trade and industrialization for Africa. China has reaped most of the benefits, and the fault lies with Africa’s lack of a strategy for engagement with China.

The three-day China-Africa cooperation forum has become the most important event on the African international relations calendar. More African leaders attend these summits than the United Nations general assembly. Data shows that the forum attracts 40 to 60 African heads of state and government, far more than any other regular summit with a single country. The US-Africa Leaders Summit in December 2022 saw participation by 45 heads of state and government and 49 countries, but it is far less frequent. The previous one was in 2014.

Although the EU, France, South Korea and the US are important to the African continent, they do not have the same ambition that China has. Nor the kind of free hand that China’s authoritarian system allows its leaders. The Forum on China-Africa Cooperation is therefore important for African leaders because it often leads to big promises which outweigh anything that can be promised by other partners in one sitting.

The forum’s defined purpose is to be a platform for “equal consultation, enhancing understanding, expanding consensus, strengthening friendship and promoting cooperation.”

It has become clear, however, that the forum is a platform for China to dole out aid and loans to African countries, and to articulate priorities that serve its own broader ambitions. Africa’s voice is minimal in the agenda-setting, due mostly to the multiplicity of African states, African Union weakness and competing needs among African countries.

Africa needs a concerted approach towards China and all of its so-called strategic partnerships. The AU Commission should negotiate and set the overall direction in these forums.

Since its inception, the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation has seen China promise tens of billions of dollars in aid, investment and loans to African states. The figure most often cited in recent years is the US$60 billion to be disbursed over three years, first between 2015 and 2018, and then between 2018 and 2021.

However, there is some ambiguity about this committed figure. It is not clear how much of this amount has actually been disbursed, indicating that China may have not lived up to its promises. No official statistics have been released, and the African side has not insisted on a more transparent approach. So Beijing has near absolute power over information and the discourse about the relationship. China also reportedly broadens definitions of what counts as aid (by including interest-free loans under this category, for example) to suit its political needs.

Africa needs a concerted approach towards China and all of its so-called strategic partnerships. The AU Commission should negotiate and set the overall direction in these forums.

What has been observable, however, is the level of infrastructure and industrial cooperation between Africa and Chinese companies, some with partial state ownership.

Chinese companies have cooperated with African governments in constructing railways, airports, harbours, bridges, and information and communication technology infrastructure. These, however, are the products of bilateral engagement between China and individual African countries, as they pursue their own foreign policies, more than any collective African strategy. The piecemeal engagement leads to greater bargaining power for the Chinese side.

My research shows that the gains from bilateral deals largely go to China: the equipment, high-level personnel and technical experts come from China. There has been little to no technology and skills transfer from China to Africa. The local populations mainly participate in labour work and government relations in the projects.

China has had a long-standing Africa Strategy, published in 2006. Nearly two decades years later, Africa has none.

The strategy presents China as seeking to be a partner in Africa’s development, while recognizing the continent’s mineral and strategic value. More than any other major power, China has pursued its relationship with Africa in a concerted long-term fashion. For its part, Africa has not been proactive and still engages with Beijing in an individualized and haphazard manner.

One of the many hindrances to following a single African strategy towards China is the number of countries on the continent. The forum encompasses nearly all African countries with the exception of eSwatini, which maintains diplomatic relations with Taiwan. On the face of it this would appear to be an advantage for Africa: more than 50 states against one. However, the advantage is towards China, which operates as a single actor and can have a coherent set of objectives across governments over a long period.

Then, there’s the weakness of the African Union.

The African side does have, at least on paper, a single entity. The AU Commission, which is headed by a chairperson elected by the AU’s Heads of State and Government Assembly to a five-year term (renewable once), is empowered to draft Africa’s position in international negotiations.

However, the reality is that most African states prefer individual sovereignty over a pooled approach. The AU Commission chairperson has no special privileges or directive powers over the African position at the China forum.

The result of a lack of an African strategy is the imbalanced terms of trade between China and African countries. This is seen most notably in the trade surplus that China enjoys: most recently measured at US$64.1 billion as of 2023 and still seemingly growing (having been at US$46 billion the previous year and US$42 billion in 2021).

Over the past ten years, the structure of that trade has not changed, despite China’s pledge to help Africa industrialize.

African countries still largely export raw minerals and agricultural goods to China, while it sends back advanced manufactures, such as electronics, machinery and vehicles. Without an African strategy, the same pattern looks set to continue.

Bhaso Ndzendze is Associate Professor International Relations at the University of Johannesburg. This article was first published on The Conversation.