Art, Light and a Tasteful Lack of Oligarchs at the Venice Biennale

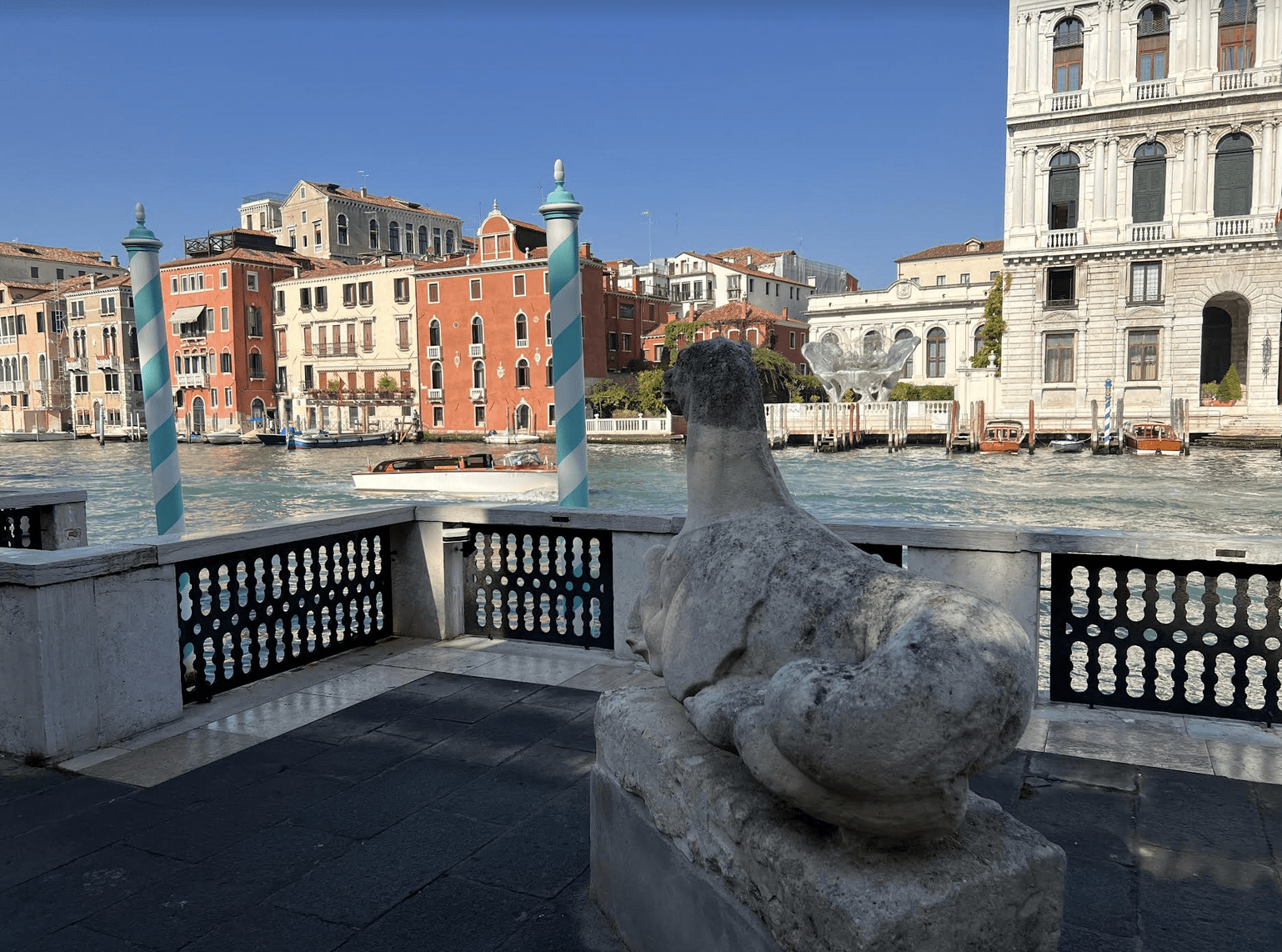

The view of the Grand Canal from Peggy Guggenheim’s palazzo/John Delacourt

The view of the Grand Canal from Peggy Guggenheim’s palazzo/John Delacourt

John Delacourt

July 13, 2023

The late art critic Robert Hughes, in his last book Rome: A Cultural, Visual and Personal History, wrote that the flood of tourists every summer had made experiencing the art of the city virtually impossible. Too many bodies crammed into each room of every museum and gallery like a Tokyo subway car, too many cellphones vying for the perfectly framed shot of a masterpiece. While in Venice for the first Biennale after the pandemic, I couldn’t help but think Hughes had seen into the future and decided to check out before what he experienced in Rome spread to other capitals – just like, say an epidemic. And yet, as I ascended the stairs of the Palazzo Ducale, entered a room as large as an aircraft hangar and took in the huge, magisterial canvases of Anselm Kiefer’s exhibition, titled These Writings, When Burned, Will Finally Cast a Little Light, I realized there’s something to be said for the madness of crowds, and that I’d happily take my place in the procession of this secular pilgrimage, to take in what the soul requires after the plague years.

It has been a little over a year now since the idea of travel — not for conferences or business meetings or brief visits with family, but for actual, sustained encounter with another place and another culture — was once again worth considering. I still remember that moment of realization, here in Ottawa. It wasn’t as though the pandemic was behind us, but as I went for a morning swim in a nearby pond where neighbours gathered, the codes of distance, like the spring chill on the water, had evaporated. After close to three years of peering out at the world through screens – through Zoom meetings, doom scrolling, binge watching whatever movie or series approximated the world as we once knew it before lockdown – I could sense that the muted cordiality and the masked aversion of eye contact had been shaken off at last among us swimmers, who were all a little heavier and paler from our winters of imposed seclusion. I remember walking through a wooded passage back to my neighbourhood, with the one destination, clear in my mind, where I would suggest to my wife that we should go: Venice, for the first Biennale since 2019.

I had my reasons. And thankfully, given the savings we had accumulated over the pandemic, we were fortunate enough to say we had the means — not something one takes for granted in these times. My interest in the Biennale was sparked by an uncle who taught art history in Toronto and Dublin. He became a kind of mentor, who taught me how to look closely and appreciate the formal qualities of paintings that rewarded sustained attention. Over the last decade I’ve written three novels that have focused on the art market as a kind of nexus of geopolitics, economics, and the way these outsized forces exert their influence on the work and our understanding of what we value.

Which, of course, has a strong political dimension. Value itself in the art market has become so abstracted and vulnerable to speculation over the last half-century that, as a commodity, works of art have outperformed virtually every other asset class for investment. But such abstraction and speculation inevitably attract the extravagantly fraudulent as well as the extravagantly talented, and among the prospective clients of art dealers, it also attracts a multinational mix of aspirational one-percenters, all seeking quick returns on investment within this parallel economy. It’s a Balzacian demimonde that reflects, like the canals that flow through la Serenissima, a wavering, mirror image of the abstracted, speculative component of world markets.

Author John Delacourt at the 2022 Venice Biennale

And in 2022, that parallel economy was driven by more than just the aftershocks of the pandemic. The Russian invasion and criminal occupation of Ukraine, as acutely felt as it is in Europe, cast an even larger shadow over the Biennale, given how pervasive the influence of Putin’s oligarchs have become, over the last two decades, in the art market. Indeed, much like the incremental hoovering up of luxury properties in London, transforming parts of Belgravia and Knightsbridge into “ghost streets” where “iceberg houses” are empty for most of the year, the dizzying, multimillion dollar art transactions that have periodically made the front pages over the years would not have been possible without the influence of a select group of billionaires with ties to the Kremlin.

Nothing could have been more emblematic of this than the controversy caused by steel magnate and Putin crony Roman Abramovich mooring his super yacht Luna along the Grand Canal in 2011. The locals fumed about the vulgarity and the hubris of this gesture but it simply made explicit the realpolitik of the Biennale; you could speak of how this was an international competition that celebrates, as the curator Cecilia Alemani put it, “the freedom to meet people from all over the world, the possibility of travel, the joy of spending time together, the practice of difference, translation, incomprehension, and communion.” But it has also been a gathering where, like a draft event for the NBA or the NFL, the media, the money people, the celebrities and the celebrity-adjacent, mix among the dealers and artists to scout which properties will “earn out” long after the mega-yachts have set off for other ports of call.

However, there were no mega-yachts to be seen along the Grand Canal with the 2022 return of the Biennale. And the stately Russian pavilion, painted a mossy green, as if it might somehow humbly slink back into the foliage of the Giardini, was locked up and shuttered. A sole Italian security guard, chain smoking, committed to his mid-summer dolce far niente flex, casually stole glances at his phone as he stood watch at the entrance. The Russians were blessedly inconspicuous by their absence; at least this seemed to be the sentiment of most of the visitors looking the other way as they wandered from pavilion to pavilion on the grounds.

As it was for the locals as well. The Salizada San Moisè is a narrow alley of name brand boutiques in the San Marco district, not much of a walk from Harry’s Bar and a local parish church that has a Tintoretto on its walls (and where the Scottish financier John Law, who created one of the first private banks, is rather appropriately entombed).

Canadian curator Tamara Andruszkiewicz/Food & Wine Trails

In a restaurant called Bancogiro, near the Rialto bridge, Tamara Andruszkiewicz, a strategic liaison for the Canadian presence at the Biennale and sommelier who first travelled to Venice in 1993 to help organize Canada’s participation (and has stayed on since), told us of how pleased most Venetians were that this “shopping mall” of a corridor was hardly busy at all over the summer. The Russians had become how Americans were viewed after the war: carpetbaggers and philistines, not much different than the Goths who first sacked Veneto in the Dark Ages.

Andruszkiewicz has done what she could — striven to offer visitors the best reflection of Canada by hiring talented Pluto-lingual young people as gallery attendants, helping to ensure the Canadian presence is the furthest thing from a Barbarian invasion (however, there is a real opportunity for one of our esteemed philanthropists to fund a Canadian internship program). Mercifully, when an entry was as strong as last year’s, with Stan Douglas’s installation 2011 ≠ 1848, most visitors could have been left with the distinct impression our artists are capable of a clear-eyed, complex and compelling response to the darker undercurrents roiling beneath the terraces and the grand facades the tourists solemnly frame and capture on their iPhones.

From Stan Douglas’s 2011 ≠ 1848 at the Venice Biennale/Jack Hems via National Gallery of Canada

From Stan Douglas’s 2011 ≠ 1848 at the Venice Biennale/Jack Hems via National Gallery of Canada

Douglas’s 2011 ≠ 1848 consisted of four, staged, panoramic photographs that evoke four spectacles of social unrest in 2011 (yes, the year of Abramovich’s Luna on the Canal) with remarkable similarities to the events of 1848 in Europe: the Arab spring’s “curfew protest” in Tunis, the Occupy Wall Street protest in New York, the riot in downtown Vancouver after the Canucks lost in the playoffs that year, and a similar violent uprising in Hackney, London. The Vancouver artist couldn’t have anticipated how prescient this installation seemed to visitors from Ottawa, with fresh memories of the Convoy Occupation. Although Douglas’s work was ultimately not in the running for the Golden Lion, the installation was elegantly mounted within the pavilion like a diorama that depicted the intimations of a new divide emerging, one we’ve only begun to reckon with here at home and around the world.

While, Venice, and perhaps all of Europe, have begun to reckon with the sudden evaporation of the Russian presence on the continent, the city that inspired Joseph Brodsky’s paean Watermark, where Stravinsky and Diaghilev are buried, where Dostoyevsky wandered and Tolstoy brooded, has always had something of the elegiac intrinsic to its beauty. We can only hope the darker shadows of conflict won’t occlude that rare and famous light that no artist from Canaletto to Turner, that no iPhone image – only memory – can truly capture.

Policy Contributing Writer John Delacourt is Senior Vice President of Counsel Public Affairs and author of the novels Ocular Proof, Black Irises, Butterfly and Provenance.