And Now for Something Completely Different

By Douglas Porter

May 10, 2024

After banging on for much of the past year about the widening growth gap between the U.S. and Canada, this week’s thin slate of data put our drums on pause. The few U.S. morsels on offer landed on the soft side, while Canada’s employment report—sometimes known as the random number generator—pulled its usual surprise with a huge headline gain of 90,400. In the relative U.S. data void, Treasuries digested the quarterly refunding and saw yields barely budge on net for the week, with 10s ending back close to 4.5% and 2s nudging up to 4.85%. With the U.S. rate backdrop mostly calm, stocks remained in rally mode, with the Dow working on an 8-day winning streak and the S&P 500 again moving within reach of its all-time high.

What this week’s crop of U.S. indicators lacked in star power, it made up for with surprise. Jobless claims have recently only been notable by their preternatural calm, barely moving from around the (very low) 210,000 level for the past seven months. But they crossed everyone by suddenly popping to 231,000 last week, a high for 2024. Meantime, consumer credit slowed to just a $6.3 billion increase in March (the average monthly gain in the past ten years is closer to $16 billion). This cut the yearly growth rate to just 2.3%, the slowest pace in the past 30 years, aside from the GFC and the pandemic. And, consumer sentiment fell heavily in May, as per the University of Michigan, as long-term inflation expectations rose to 3.1%. For yields, the last point dominated the soft results elsewhere, keeping Treasuries little-changed for the week.

Canada’s fixed-income market was much less serene, with the jobs report setting the cat among the doves. Two-year GoC yields bounced 10 bps on the week, as the blowout headline employment gain reset expectations on the Bank of Canada’s coming rate decision on June 5. After leaning heavily to a rate trim in the wake of last week’s mild U.S. payroll report, market pricing is back to leaning to a rate hold for June.

Our view on Canadian employment reports is generally that they are so volatile that the Bank of Canada doesn’t read that much into them, and neither should we. Admittedly, it’s tough to ignore such a gaudy jobs gain, particularly when many still believe recession risks are real in Canada. However, what was at least as notable as the big employment rise was the fact that the unemployment rate did not benefit one iota, holding steady at 6.1% and up a full point from a year ago. A rough rule of thumb is that a 25% y/y rise in the number of unemployed people usually equals recession—and Canada is now up 24% y/y. How can we possibly have had such a dismal reading when jobs are so strong? Let’s break Canada’s jobs picture down over the past year:

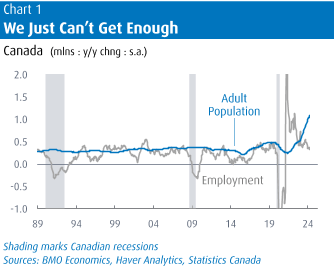

- The adult population (15+) is up 1,081,000 people;

- The labour force has risen 633,000 (58.6% of the population growth);

- Employment has in turn risen by 377,000 (just 59.5% of the labour force growth);

- Unemployment has risen by 256,000 (the difference between the labour force and employment).

Notably, even with the hefty April rise, the increase over the past year is less than 400,000 net new jobs at a time when the adult population posted its strongest gain on record (at 1.08 million). This implies that less than 35% of net new adults were employed at the margin, versus an economy-wide employment rate of 61.4% last month. The bottom line is that the economy is simply not able to create enough jobs to keep up with population growth (Chart 1), and that was even the case in April. (At the second decimal place, Canada’s unemployment rate rose 0.05 ppts last month, even with the jobs spike.)

Wages actually calmed a bit to 4.7% y/y in April, and all of the jobs were in the service sector, with a slim majority of the part-time variety. The main point for policymakers is that economic slack is thus still building, putting additional downward pressure on prices. So, while the kneejerk market reaction was to markedly reduce the chances of a near-term rate cut by the Bank of Canada, that’s not the obvious answer.

Having said all that, there is no doubt that the hearty jobs report will give the Bank some pause. When it was already a close call on whether to begin trimming rates, a rollicking headline jobs gain is hardly the cover needed to begin the process. The Bank also released its annual Financial Stability Report this week; while many of the headlines focused on the coming jump in mortgage payments, the more important takeaway was that households are so far managing the rate rise reasonably well. In fact, the bigger concern was for renters, who are dealing with rapidly rising rents, along with sticky inflation, and a tougher job market.

We are very reluctant to suggest that the Bank’s June rate decision may hinge on one lone economic indicator—the CPI report on May 21. Accordingly, we’ll point out that the first hurdle will be next Wednesday’s U.S. CPI. Another sour result there may well sink rate cut prospects overall, as it would reinforce the message that inflation truly is stuck at just above 3%. Our call, which is mostly in line with consensus, is hardly reassuring, with total prices expected to rise 0.4%, and core up an uncomfortable 0.3%. While these are just mild enough to trim the annual rates (to 3.4% and 3.6%, respectively), note that in the 15 years to 2021, there had never been a single month when U.S. core CPI topped 0.3%. We have seemingly become inured to higher readings. Suffice it to say that in such an environment of still-meaty U.S. inflation, BoC hesitancy is perfectly understandable.

At least the Bank of Canada will not be on its own if it decides to begin cutting rates. This week’s Bank of England decision to hold rates steady saw two members vote for a cut, and the message opened the door for a June move. The ECB has been loudly hinting at a June cut as well, and we’re on board with that call. Meantime, Sweden’s Riksbank walked the walk this week, becoming only the second G10 central bank to cut rates, following Switzerland’s lead earlier this year. Sweden cut 25 bps to 3.75%, moving ahead of the ECB, where the refi rate is higher at 4.5%. However, the Riksbank may not be a great guidepost for the BoC, as the case for a rate cut there was very strong. Sweden has been in a clear-cut recession for the past year, with GDP dropping for four consecutive quarters, and the unemployment rate jumping 1.5 ppts in the past year to a meaty 8.6%. It’s good to have company, but one has to watch the company one keeps.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.