An Excellent Gallery Close-up

Robert Lewis

Power, Prime Ministers and the Press. Toronto, Dundurn Press, 2018.

Review by Anthony Wilson-Smith

If there were a hall of fame for Canadian political journalists, Bob Lewis would surely be in it. As a Parliament Hill reporter and bureau chief for three publications, starting in the mid-1960s to the end of the 1970s, he was as respected as he was liked by all sides. He went on to become managing editor and then editor of Maclean’s magazine for another two decades, while his influence on the Hill remained undiminished.

The qualities that defined him as a person—his genial manner, intelligence, innate fairness, and keen eye for detail—also distinguished him as a journalist. When I arrived in Ottawa for my own tour as bureau chief and columnist for Maclean’s in the 1990s, the first question prime ministers Brian Mulroney and then Jean Chrétien asked was the same one: “So, how is my old friend Bob?”

Few people have had a closer view of Canadian federal politics up front, and even fewer have Lewis’s level of understanding of its sweep and sometimes subtle nuances. That is evident in Power, Prime Ministers and the Press, his new book on the historic love-loathe relationship between the Parliamentary Press Gallery and the government of the day. (It is also, surprisingly, Bob’s first book ever.) Just like the politicians they cover, the journalists that Lewis writes about—starting in the early 1900s and extending to the present—run the gamut from biased to balanced; bland to blustering; sober to scotch-soaked. The one trait they almost all share is an obsession with the daily drama of politics.

Few people have had a closer view of Canadian federal politics up front, and even fewer have Lewis’s level of understanding of its sweep and sometimes subtle nuances. That is evident in Power, Prime Ministers and the Press, his new book on the historic love-loathe relationship between the Parliamentary Press Gallery and the government of the day. (It is also, surprisingly, Bob’s first book ever.) Just like the politicians they cover, the journalists that Lewis writes about—starting in the early 1900s and extending to the present—run the gamut from biased to balanced; bland to blustering; sober to scotch-soaked. The one trait they almost all share is an obsession with the daily drama of politics.

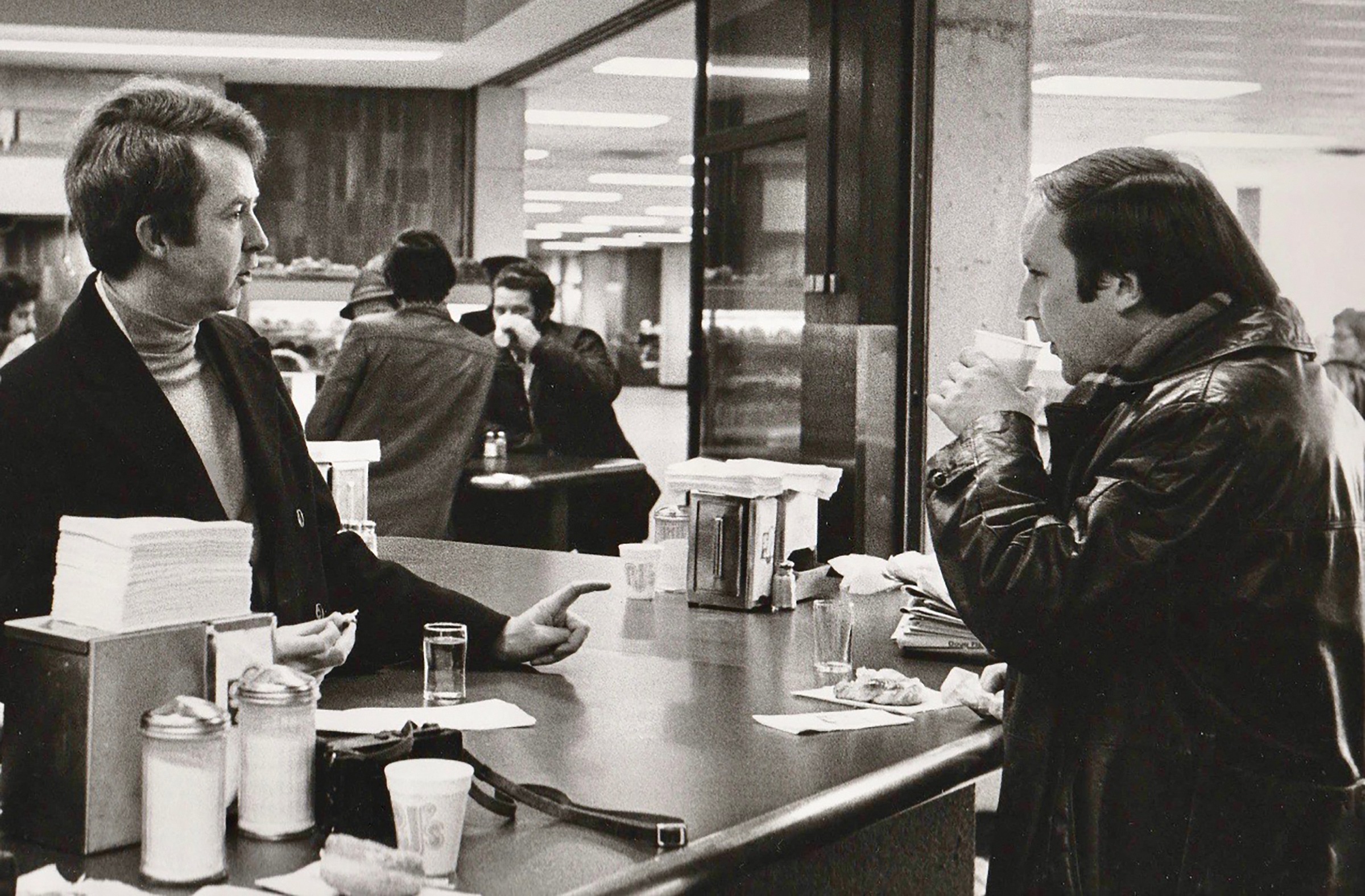

That makes for no shortage of colourful characters to write about, and Lewis makes the most of their foibles. For much of the 20th century history of the Gallery, its members—almost exclusively male for most of that time—enjoyed cozy, first-hand relationships with the subjects they covered. That included the ability to drop in on various prime ministers for a drink, to informally probe and sometimes advocate for various positions on government policy. Some of those exchanges were reported; many were not. That access gave journalists greater insight into policies and the motivation behind them—while those conversations remained off-record as an unabashed trade-off. Blair Fraser of Maclean’s, writing about Lester Pearson when he was external affairs minister, observed that “We all feel entitled to ring him up any hour of day or night…Quite often he puts his official life in reporters’ hands with a clarifying, but grossly indiscreet, interpretation of the known facts.”

No Canadian journalist today would have that first-hand exposure, or write like that. But those who think that acrimony between politicians and journalists is a new phenomenon haven’t studied the toxic relations between, among others, John Diefenbaker and the Gallery. The notoriously prickly Diefenbaker started his term in power on a friendly fishing trip with several journalists—and ended it at war with much of the Gallery. He was particularly obsessed with Peter C. Newman, whose book Renegade in Power gave the first-ever real behind-the-scenes reporting on a Canadian government in power—and eviscerated Diefenbaker in the process. In a handwritten note still on file at the Diefenbaker Canada Centre at the University of Saskatchewan, The Chief referred to Newman as “the literary scavenger of the trash baskets on Parliament Hill” and as an “innately evil person”. But Newman was no partisan. He became so adept during Pearson’s time at getting scoops on cabinet secrets that Pearson threatened to fire any minister caught leaking to him. Newman dutifully reported that revelation two days later.

Lewis recounts how his interest in writing such a book, which was four years in the making, sprung from a discussion he chaired at the Canadian Journalism Foundation. Its title: “Does the Press Gallery Matter?” That question was prompted by factors including growing distrust of the media; the sharp decline in the number and readership of newspapers; the increasing ability of political parties to bypass traditional media by delivering their messages directly online; budget cuts for those media institutions still operating—and the decline in membership of the gallery itself. (Between 2012 and 2016, Lewis reports, the Gallery shrunk by almost 20 per cent, from 370 members to 320.) Those reporters are expected to file regularly updated stories more often throughout the day on various platforms in order to keep up with the insatiable appetite of a wired world for immediacy.

Lewis sympathizes with those challenges. His “lament”, he writes is “not for a press gallery that might have been, nor for some mystical golden age.” But if the private scotch drinking exchanges between politicians and reporters in past years were too much to one extreme, then so, Lewis writes, is the present-day antipathy that ultimately diminishes both sides. By the time these elements came together in the 2015 election campaign, the need was clear, he observes, “for reporters to operate with civility, thoughtfulness and a modicum of humility—along with scepticism, and for politicians to give up the bullhorn and the lash.”

Ambitious in scope as it is rich in up-close anecdotes, Power, Prime Ministers and the Press reminds us that the way news events are reported can depend as much on the people reporting them as it does on the events themselves. What has changed so dramatically is the willingness—or lack of same—of news consumers to accept what they are told at face value. A news event only happens once, but it can be told in an infinite number of different ways.

There has never been a time in which so much information can be made available so quickly to anyone equipped with a mobile device or laptop with modem. But as Lewis argues, someone has to provide context and balance—and know how and when to ask the right questions to produce meaningful answers. That’s the job of the people in the Ottawa press gallery—and it’s arguably never been more difficult to do.

But that, in turn, leads back to the question that prompted this book: “Does the press gallery still matter?” As Lewis rightly concludes: “Now, more than ever.” And so, by extension, does this excellent book.

Anthony Wilson-Smith, former Ottawa bureau chief and later editor of Maclean’s, is President and CEO of Historica Canada.