All Parliament, All the Time: Life in a Minority Government

When Pierre Trudeau’s first, Trudeaumania-fueled majority was followed by the hangover of his 1972 minority government, the Liberal team adapted its approach and tone, writes longtime Pierre Trudeau advisor Tom Axworthy. Axworthy, who remained with Trudeau during Joe Clark’s minority government of 1979-80 and beyond, provides invaluable perspective on the minority governing experience from both sides of compromise.

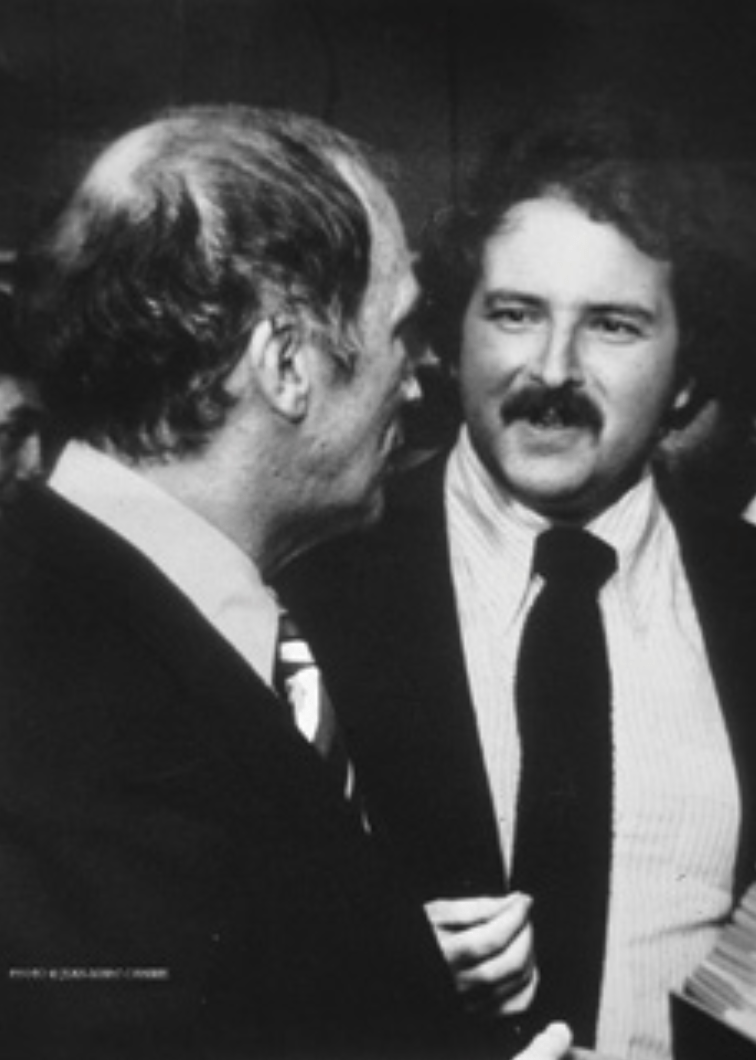

Thomas S. Axworthy

“Two cheers for minority governments,” exclaims Professor Emeritus Peter H. Russell of the University of Toronto, one of Canada’s most distinguished political scientists. Russell’s argument is that majority governments are too easily dominated by the prime minister and the coterie of unelected advisors in the Prime Minister’s Office which, in turn, reduces the role of ministers and MPs, “thereby weakening parliamentary democracy itself.”

The main difference between majority and minority governments in the parliamentary world, he writes “is in their method of decision making. The difference is fundamentally between a system in which the prime minister dominates the decision-making process and a system in which policy-making is subject to the give and take of parliamentary debate and negotiation.” As Eugene Forsey, another constitutional sage, put it: “A government without a clear majority is more likely to stop, look, and listen.”

Russell and Forsey are correct. Parliament can’t be ignored by a minority government as the government’s very existence depends upon securing a majority of members on votes of confidence. I served as a junior policy advisor in Pierre Trudeau’s minority government of 1972-74 and was in his Opposition office during Joe Clark’s minority government of 1979-80 and, in both cases, it was “all Parliament, all the time.”

A prime minister still has the predominant role in deciding upon the government’s agenda and legislative priorities in a minority situation. But, unlike in a majority government context, his will alone does not resolve the issue. Compromise, adjustment, and understanding the priorities of the other parties are the order of the day. So, a parliament of multiple parties with none commanding a majority is a countervail to the growing power of an imperial prime ministership.

Countervail, however, is a checking mechanism. There is a broader, more positive, even idealistic vision of Parliament. The key starting point is that governments are not elected, MPs are and governments arise out of Parliament if they can command a majority of members. Another distinguished Professor Emeritus, David E. Smith, thus writes: “Government and Opposition are part of a shared community-Parliament.” As the only elected part of Canadian government, “the House of Commons,” Smith writes “is Canada’s premier institution for the authoritative expression of electoral opinion and for approval of public policy formulated in response to that opinion. The House of Commons is the voice of the Canadian people, the one place where the people’s representatives from all regions can debate and legislate.” To quote Smith again, “Parliamentary debate is a great leveller of conflicting interests as well as a calming influence on intense feeling”.

Canada will need Parliament as a national articulator and conciliator of conflicting interests and, even more hopefully, as a calming influence, because the 2019 election revealed a country deeply divided on critical issues of the environment, the economy and regional fairness.

The campaign was bitter and nasty (recall that in his opening remarks, in the English-language debate, Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer began by calling Justin Trudeau a “phoney and fraud”). Social media trolls were hard at work, too, spewing rumor, disinformation and scurrilous personal attacks.

The election results reflected this mood, with no party being happy about the result except the Bloc Québécois. But the Liberals can negotiate with either the Bloc or the NDP to win majority votes in the House, so there is room for manoeuvre if the Trudeau Liberals are adept.

But the results may be a portent of a looming national unity crisis bookended in two regions: in Quebec, the Bloc was a close second to the Liberals with 32 percent of the vote compared to the Liberals’ 41.5 percent and 32 seats to the Liberals’ 35. A party espousing sovereignty is again a major force in La Belle Province. On the Prairies, it was a stupendous victory for the Conservatives and a near-shutout of the Liberals: in Alberta, the Conservatives rolled up 69 percent of the vote to the Liberals 13.7 percent, and in Saskatchewan the Liberals did even worse with only 11.6 percent of the vote compared to 64 percent for the Conservatives. Of the Prairie provinces, only in Manitoba did the Liberals have a decent showing, with 26 percent of the vote and four seats—the only seats won by the Liberals between Ontario and British Columbia.

Given the startling polarization of the 2019 election, is there any chance that the hopes of scholars like Russell and Smith for collaboration and positive outcomes in the new minority government will be realized?

History, at least, offers one positive precedent—the 1972-74 minority government of Pierre Trudeau. There are significant parallels between the two Trudeau minority governments: in 1972, Trudeau faced an American president who had recently imposed economic penalties on Canada and had little love for the Canadian PM, although Richard Nixon was not as erratic as Donald Trump. The Parti Québécois was steadily building support for separatism at the same time as a “New West” was being proclaimed by the dynamic Peter Lougheed in Alberta.

So, as today, regional tensions were felt on two fronts. Back then, the federal government had a core policy—the Official Languages Act— based on a fundamental principle of national bilingualism that went down particularly badly in the Prairies (the National Energy Program was still nearly a decade off).Today, the regional irritant is a carbon tax to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the fight against climate change, which the recent Speech from the Throne said was “the defining challenge of the time.” That’s not a definition that appeals to the Conservative Party as the carbon tax is stoutly rejected by the conservative premiers of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Ontario.

Pierre Trudeau responded to these multiple pressures (and the shock of being nearly defeated in October 1972) with a fundamental change in approach and tone. Liberal House Leader Allan MacEachen, the parliamentary wizard from Cape Breton, was given a mandate to negotiate secretly on the legislative agenda with David Lewis, the leader of the NDP and the new Liberal stance was one of contrition, accommodation and compromise. The creation of Petro-Canada and other positive measures were the result. And it was not just the NDP who were accommodated: in perhaps the most significant and long- lasting reform of the 1972-74 minority government, Finance Minister John Turner, in 1973, adopted the major plank of the 1972 Conservative platform to index the country’s personal tax rates to inflation, thereby eliminating the hidden revenues accruing to governments through the effects of inflation on a progressive tax system. In 2019, the Justin Trudeau government pledged to be as accommodating as its long-ago predecessor, proclaiming in the Speech from the Throne that in the 43rd Parliament “this government is open to new ideas from all Parliamentarians.”

Regional tensions are endemic to Canada—they can never be eliminated, only managed. The starting point in managing them is to ensure that regional perspectives are well articulated in all policy debates. Facing a resurgent Bloc, a prominent Quebecer should be recruited to the PMO and with no cabinet representation from Alberta and Saskatchewan, the need is even greater to have senior advisers from the Prairies at the centre of the action. Responding to a similar Prairie political drought in 1972, Joyce Fairbairn and Jim Coutts, both from Alberta, became key advisors to Pierre Trudeau. Cabinet-making is a key part of the puzzle too: Justin Trudeau’s options were limited by the Liberal shut-out in Alberta and Saskatchewan but he made some astute moves to quell the Prairie fire by naming Chrystia Freeland deputy prime minister and minister of Intergovernmental Affairs (after negotiating NAFTA II with Donald Trump’s team, even Jason Kenney will be a relief) and she was born and raised

in Alberta.

Wise appointments can fill some of the regional gaps, but a more fundamental change is long overdue. One of the key functions of the Senate when it was created in 1867 was to represent the interests of the regions: instead, through most of its history, party interest, not regional representation was its organizing focus. In one of his most significant reforms, Justin Trudeau broke the excessive partisanship of the Senate by appointing independent senators without party affiliation. Such independents are now a majority of the Senate. But as Hugh Segal and Michael Kirby, two former senators, make clear in their 2016 report, A House Undivided, the regional role of the Senate is still underdeveloped. The Senate is now organized into various groups: the largest, at 49 members, is the Independent Senate group; next is the Conservative group (26); nine senators in the Progressive group, various non-affiliated Senators, and, just recently formed, a Canadian Senators Group of 11 members largely made up of former Conservatives. The new group is dedicated to representing their various regions. The next stage of Senate reform should be to ensure the original vision of the Fathers of Confederation to have a second House alert to the fundamental characteristic of Canada’s polity—the enduring strength of regions.

Representation of the regions is crucial but so, too, are policy outcomes. Here, the new minority government could have lots of running room. Often it is best when faced with pronounced regional divides not to make it a zero-sum game by a frontal assault on a given position but instead to achieve the objective by finding new routes to the promised land. The throne speech posits a new goal of net-zero emissions by 2050, but the problem is Canada has made little progress in achieving much less ambitious goals.

How should Ottawa proceed? The carbon tax is but one of many policy instruments, albeit one that’s like waving a muleta to the Conservative bull. So, maintain the existing tax, but concentrate on a massive building-refit program to ensure that the built environment contributes mightily to energy efficiency. Similarly, some Albertans are upset with the federal equalization formula negotiated by Stephen Harper (with Jason Kenney a senior member of that government).

It is the principle of equalization that is important, not the details of a particular formulation. The Fiscal Stabilization Program is intended to help provinces when they experience a sudden drop in revenues, a complement to equalization where richer provinces contribute to providing an equal base for public services across the land. If Alberta and Saskatchewan have a good case that the stabilization fund needs to be topped up to help with the very real difficulties that they are in, then Ottawa should do it. The point is to ensure that Canadians know that their region has received a fair hearing and that the Confederation dice are not loaded against them.

In response to the western dissatisfaction of his day, in July 1973, Pierre Trudeau and his key ministers met the Western Premiers at the Western Economic Opportunities Conference, (WEOC) the first time the prime minister had met a subgroup of premiers in an official gathering. The political situation today is very different (Pierre Trudeau had to contend with three NDP premiers and one Conservative, Justin Trudeau instead would meet three Conservative premiers and one NDP stalwart) but the concept still has merit today.

If the Trudeau government must respond to the changed circumstances of a parliament without a one-party majority, so, too, should opposition MPs. One crucial area that they should cooperate on is reforming Parliament itself to enhance the role of MPs and roll back the excessive powers of the executive. In a minority setting, much can be done to correct past abuses while giving MPs a more meaningful role.

New Zealand has a protocol, agreed to by all parties, on how parliamentary business in a minority government should be conducted. Canada has need of such a protocol, which should cover topics such as the election of chairs of parliamentary committees, the prorogation issue, the misuse of omnibus bills, more strict definition of non-confidence motions which would encourage MPs to vote their conscience, and a review of what accountability should mean for a 21st century parliament, since so many ministers deny their personal responsibility for what departments are doing. It is especially important to make the committee system work. Becoming a committee chair should be one of the desirable and important jobs in Parliament, open to MPs of all parties and decided by secret ballot. One step in the right direction was taken in December, when members of Parliament voted to create a special committee on Canada’s relationship with China.

In 1973, the minority Trudeau government, prodded by the opposition parties, strengthened Canadian democracy by amending the Elections Act to regulate election expenses for the first time, establishing the election regime, which still stands, of disclosure of donations, political tax credits and the reimbursement of political party election expenses. It was a landmark achievement.

Today, the 43rd Parliament has a similar opportunity to make our parliamentary democracy work better both by strengthening the powers of individual MPs and parliamentary committees and by enhancing the representation of regional interests at the centre of government. If that occurs in this new minority parliament, it will earn not two cheers but a grand “Hurrah!”

Contributing Writer Thomas S. Axworthy is Public Policy Chair at Massey College, at the University of Toronto. He was principal secretary to Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau from 1981-84.