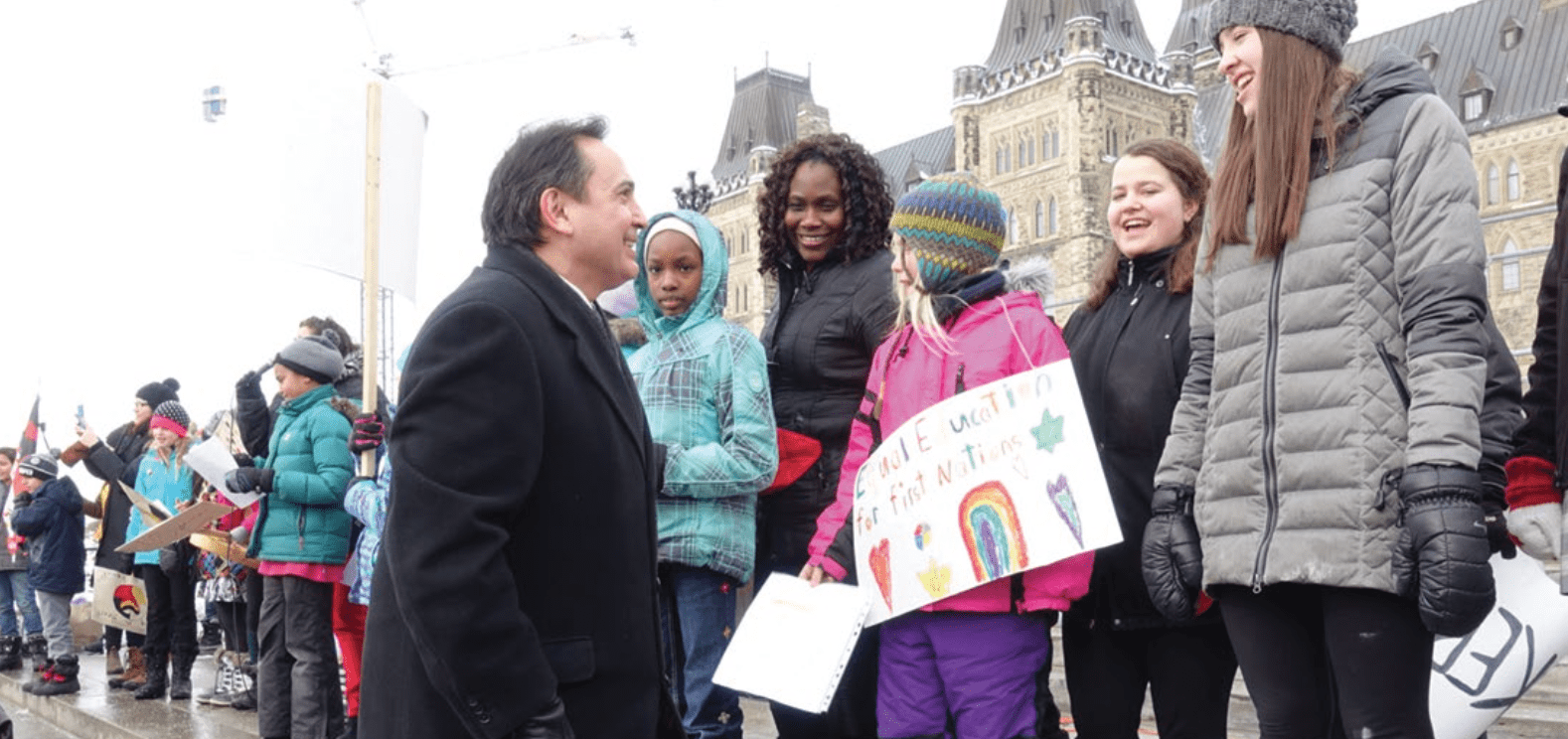

AFN National Chief Perry Bellegarde: ‘Moving in the Right Direction’

As he prepared to step down as National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, Perry Bellegarde sat for a con- versation with Policy Editor L. Ian MacDonald, rang- ing from the residential school crisis to the growth of Indigenous businesses, including innovation addressing climate change.

Policy: Chief Bellegarde thank you for joining us in doing this today.

Chief Perry Bellegarde: Happy to do it.

Policy: One of the things on the news agenda, of course, is the residential school crisis—not a new subject for you. And of course, it’s not just the Kamloops 215, but thousands of others, as you’ve pointed out. And, despite the Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, nothing has been done to locate the other sites. I wonder in terms of oral history and what you learned about, heard about this growing up in Saskatchewan at your mother’s knee?

Perry Bellegarde: I would say there were two things in Canada that really hurt First Nations people in a very negative way, and we still feel the intergenerational trauma and effects of them. One was the residential school system itself. The last one closed in 1996. I called the residential school system a genocide of our people. It broke down identity, broke down self, it broke down family, broke down community, broke down nationhood, then inflicted abuse on these beautiful children. Sexual abuse, physical abuse, mental abuse, starvation, malnutrition, diseases, lack of proper health care, overcrowded conditions. So, it was a genocide at residential schools.

Everything good about being a First Nations person was no good. Your beautiful long hair was cut. Your names were gone. Your languages were outlawed. So, we still feel the intergenerational trauma because you’re not healthy when you come out—if you survived those institutions. You don’t know how to raise a healthy family, you don’t know how to love and care. So, we feel the intergenerational trauma even now. And that’s reflected in 40,000 children still in foster care, it’s reflected in disproportionate numbers of our people in jails and the high numbers of five to seven times youth suicide.

Then the other one was the Indian Act, the colonization and oppression. We weren’t allowed to leave the reserve till 1951 without a permit from the Indian agent. We weren’t allowed to sell anything without a permit from the Indian agent to participate in the economy. We weren’t even allowed to vote until 1961. The Indian Act broke down our system of governance—Hereditary chiefs, clan mothers. It outlawed sundances and potlatches. Because of the residential schools and the Indian Act, it was colonization, oppression and it basically controlled First Nations people by keeping us on our little pieces of land called reserves, so that all the other lands and resources could be exploited to form Canada.

So, when you talk about the 215 children who were discovered or uncovered, it just validated all the stories we’ve been hearing from survivors for years and years and years. That there were a lot of deaths in these schools. And there’s a lot of unmarked graves in these institutions. And that’s what we’re seeing now.

We need to listen and learn from the past because our history is shared. But how do we learn from the past and chart a future forward together as people? We have a challenge now to really embrace reconciliation. And it’s hard work. To listen to the truth about how Canada was founded and provide some hope and light that we can create a better future together.

Policy: And the TRC, in its final report, the title says it all, doesn’t it? Missing Children and Unmarked Burials. Do we have any idea how many children are missing and what is being done to somehow identify these remains and return them to their families and their descendants?

Perry Bellegarde: Well, the TRC documented approximately 4,000 deaths. Children’s deaths in these institutions, but we know that’s low and that there are far more. Earth sonar technology will do the proper research investigation because you need to know where are these children from? Who are these children? What are their names? You have to look at DNA testing.

In some cases, these may be crime scenes—how old are these bodies, how did they die? All these questions have to be answered and then you’ve got to search and notify the next of kin, and the communities themselves. And then you have to bring in ceremony and all this has to be done through ceremony, and protocols and prayer. And so it’s done in a respectful way so the Elders have to be brought in together, so there’s a lot of work with this.

One TRC call to action is finding all these unmarked graves and then commemoration. All of the sites have to be done properly, so there’s beginning to be a lot of work. And I’ve said before that these 215 beautiful young spirits are waking up and they’re speaking to people and people are starting to listen—which is a really good thing.

Policy: And what’s your sense of why the government’s still in court or hanging on to litigation?

Perry Bellegarde: That one is a Canadian Human Rights Tribunal decision, and when we clearly pointed out that there is discrimination and racism that these young people faced in that system and we won a $40,000-a-case decision that these people should be compensated. I’ve said before there’s no need for a judicial review. There shouldn’t be a judicial review. You’re fighting children, just go on and work towards the implementation of that decision. Because again, you’re only a child once. You only have a childhood experience once, so we’re still looking at it.

In addition to the AFN, in this Canadian HRT decision, we are in negotiations. I’m encouraging the federal government to just come up with a proper fair settlement, so these children don’t have to go to court in any way shape or form, so that’s still the position we’re advocating.

Policy: In terms of the church and the Papal apology and the possibilities of that. One hears of First Nations being invited to Rome, perhaps to meet with senior members of the curia and even the Pope himself, possibly to do an apology in person. I expect that Cardinal Michael Czerny, who’s a Canadian, is involved in that because he’s close to the Pope. Do you have a sense of where that’s going? What would you like to see happen?

Perry Bellegarde: We’ve been working with the Canadian Council of Catholic Bishops for the last 2-3 years, building relationships because they’re a very key piece on, first, getting an audience with Pope Francis, and second, getting him to come to Canada to make a statement to the survivors here. And we’ve been working with them the last number of years, and we were planning a trip to the Vatican a number of years ago, but then there was a federal election, so that slowed down things and then COVID-19 came upon us. So, things have been postponed again, on that call to action.

It’s very important for reconciliation to have the highest office of the Roman Catholic Church come and speak to survivors here in Canada. And so, we’re going to keep seeking that audience with His Holiness Pope Francis. To have an apology from the Pope is very important. What a strong statement that would make. He’s made apologies in 2015 to the Indigenous people in Bolivia as well to the Irish people in 2010. We’re still planning to go back to the Vatican to have an audience and the Pope will be guided by spirit and he will speak from his mind, but more importantly from his heart, when survivors get in front of him.

Policy: And Kamloops would be just the site for an apology, wouldn’t it?

Perry Bellegarde: That’s where it happened but we have 130 plus sites in Canada. My dad went to Lebret Residential School in Lebret, Saskatchewan. So, he went there but there were 19 or 20 in Saskatchewan. Across Canada there were 130 residential school sites.

Policy: How was he marked by that. Did he ever talk to you about it?

Perry Bellegarde: No, my dad passed when I was 16. But we could see the influence in the sense that he didn’t want us to go to residential schools. He didn’t say why. But obviously he knew the hurt, the pain he…. You know there’s a lot of suffering, so why would you subject your children whom you love to something that’s in a bad way? So, even if we wanted to go for sports or to meet other First Nations people, we didn’t go. We were bussed into the provincial school system…It was a travesty and a very dark mark on Canada’s history.

Policy: On something more uplifting, something that seems like a good note for you to end your leadership at the AFN on. Your thoughts on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) passed by Parliament at the end of the sitting.

Perry Bellegarde: I’ve been National Chief for seven years, and I’ve been in First Nations politics since 1986, 35 years. Leadership is all about bringing people together and building relationships. And once you start doing that and you seek out processes that unite rather than divide, you can move things and you can get policy and legislation done. Bill C-15, which is the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is one very good example.

Even 10 years ago, there was no public dialogue about racism or discrimination in Canada, no public dialogue or discourse about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, or the impacts of residential schools. Ten years ago, there was no Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. So, we can see the ground we’ve gained by even having this public dialogue.

For example, the recent Throne Speech, we have never, ever had as much dedicated to First Nations issues. We had a whole chapter. A whole chapter was dedicated to First Nations issues! So it’s not only C-15. It’s C-91, the Indigenous Languages Act is complete. It’s C-92, Child Welfare is completed and there’s 40,000 children in foster care, which is why we keyed in on children and the key jewel in C-92 is that First Nations law is paramount. So, you can start focusing on prevention, not apprehension. And you may as well throw C-5 in there as well, the National Day of Reconciliation got passed. C-8, the Oath of Citizenship office which now recognizes treaty rights as well. Now C-15, implementing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. That is the road map to reconciliation in Canada.

And it creates economic certainty, because it involves the rights and title holders sooner than later in any project. People will argue that free prime form consent creates economic uncertainty. I say no, no, no. It creates economic certainty. It is the pathway to economic stability and economic investment. If you embrace the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Bill C-15, you get a national action plan that will be done in concert with Indigenous peoples. And, as well, you get a national policy and law review. So, all the laws that are inconsistent with the UN Declaration have to be brought into line.

Policy: In retrospect, do you think Mr. Harper deserves some credit for the apology he made originally in 2008, and the appointment of the TRC?

Perry Bellegarde: Well, again, there was a court challenge, there was some legal pressure. And all the powers that be at that time listened to them. So, whoever was in power, I won’t say they didn’t have a choice, but I will acknowledge leadership for embracing it and getting it done. Now we have to keep building on that. It was the Conservatives who were in power, granted, but there were also legal court cases that brought them to that place. And now, the Liberals are in power in a minority. So, you’ve got a task to implement all the calls to action.

Whoever comes to power has Crown fiduciary obligations, and even, for example, treaties. We have a treaty relationship with the Crown. We don’t have a treaty relationship with the Liberals. We don’t have a treaty relationship with the Conservatives or the Greens or the NDP or the Bloc. We have a treaty relationship with the Crown. Nations make treaties, treaties do not make nations.

Policy: Do you have a sense looking forward about the possible Charter implications of the United Nations Declaration in terms of the Constitution and interpretation by the courts? Possible invocation of the notwithstanding clause and that sort of thing?

Perry Bellegarde: No, I think you have section 35, on the Rights of Aboriginal Peoples of Canada, you have Canada’s Constitution. Supreme law of the land. Legal scholars, both domestically and international scholars, have said this international UN document declaration can be implemented within Canada’s domestic state. No problem, no question. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples does not give Indigenous peoples any new rights, it merely recognizes what we have already.

Policy: On First Nations and business success stories, that’s been emerging increasingly during your leadership of the AFN. I go back to being in the same room as Chief Billy Diamond and Robert Bourassa in 1975 when they signed the James Bay Energy Agreement. And without the leadership and the vision of those two, the James Bay Energy project would never have been built. I wonder if today’s business leaders are, in a sense Billy Diamonds; inheritors of something that’s now larger than what we had. The pipeline partnership that’s emerging for the ownership of the Trans Mountain Pipeline between the First Nations communities along the route of the twin pipeline in partnership with Pembina, and then Project Reconciliation, another First Nations group which says it would hold 100 percent ownership. You have the Clearwater deal, the Membertou nation in Nova Scotia and the leadership of Chief Tearance Paul. These are big stories and I think people are really glad to see them. Your thoughts?

Perry Bellegarde: It’s a good point. You know, economic self-sufficiency, economic development, growth. I’ve always said you can’t talk about self-determination or self-government without economic self- sufficiency tied in. It provides hope when you see Membertou getting involved with Clearwater, a multibillion-dollar fishing industry. We’re moving beyond impact benefit agreements, and we’re starting to look at equity ownership. And we’re starting to embrace that concept of the three Ps—Planet, People, Profit—and incorporating First Nations people to make sure that their sustainable economic development going forward.

Balancing the environment and economy at all fronts, we also have some First Nations that are involved in green energy. For example,

T’Sou-ke First Nation B.C., totally on solar, and they’re selling power back to the B.C. grid at T’Sou-ke First Nation Gore Plains. I think of Henvey Inlet Chief McQuabbie they have a wind farm in northern Ontario.

I think of a Gull Bay First Nation, and they have microgrids. So up in Gull Bay they’re saving 300,000 litres of diesel because of investments in the microgrid there. Also, moving into that whole clean, green energy-field geothermal at Peguis. Are you talking about the forestry sector, mining, tourism, energy, transportation, hospital, the retail sector? So, we’ve got to break it down because even though people will say we’ve got to create our own economy, I’m saying there is one economy.

There is a domestic economy in Canada, and then there’s a global economy. So how do First Nations start participating in the global economy and as not only consumers of goods and services but producers of goods and services? It’s all about demand and supply.

And so we’re fitting into that supply chain now as First Nations people and having access to land and territory and resources, with our rights being recognized. We’re getting involved in the forestry sector, the whole softwood lumber issue because First Nations are getting involved in that industry. What are some of the biggest barriers to First Nations participation in the economy? The biggest one was a lack of access to capital. So, the Infrastructure Bank has a big role to play. Then, capacity building, technical expertise, even infrastructure having access to high speed Internet.

The other aspect was where is the procurement policy? Federal government-wise and provincial government-wise, having a percentage of these government contracts dedicated to First Nations entrepreneurs and businesses. So, between procurement, between access to capital, between capacity and the bonding issue, all of these things were barriers to creating economic growth, sustainable growth but as well, employment opportunities. And I think there is movement now that those challenges and hurdles are being overcome. And you’re going to start seeing greater economic self-sufficiency amongst First Nations people and a greater participation in the economy and wealth creation and job creation. And that’s a positive thing going forward and moving beyond this thing called the Indian Act. I see a lot of light happening now.

Policy: And going forward in terms of our largest trading partner, the United States, how do you see the trans-border issues in terms of sovereignty and so forth? Between First Nations and some of your Native American colleagues.

Perry Bellegarde: Well, number one—we always say it first—we didn’t create the borders, right? The Canada-US border: we didn’t create that border. We’ve always had trade between our nations and tribes and we still have that trade, I would say that people need to embrace the Jay Treaty, which is recognized by the USA but not yet by Canada, that will help promote trade between our nations and tribes. I think there was some movement made with CUSMA, the Canada-US-Mexico Agreement, in which we tried to get a whole Indigenous Peoples’ chapter. We had gender. We had environment. And we were looking at a First Nations chapter. We didn’t quite get that chapter in there, but there are some powerful words within that international trade agreement. If Canada wants to get involved in the world and start trading some of these natural resources, from a First Nations perspective, how are we involved as Indigenous peoples? We should be involved in shipping potash through the world. We should be involved in dealing with softwood lumber to our biggest trading partner. And the different energy sectors as well. There’s a huge role for Indigenous peoples to play on a global stage, and that’s starting to be recognized.

Policy: I wanted finally to ask about your in legacy terms and how you’ve run the AFN, led the AFN over the years. I wonder, how does the Chief of the AFN keep more than 600 other chiefs happy and on board?

Perry Bellegarde: When I took office seven years ago, I was asked that question. We’re so diverse, we have 60-plus different nations or languages across Canada. We have historic pre-Confederation treaties, Wampum treaties. You have the Treaty of Niagara in 1764. You have the Silver Covenant chain. You’ve got the Victorian Treaties in the 1800s. You have modern day treaties. You have territories with no treaties. So how do you bring about unity and working together as a collective? We have collective rights. And the most important thing is that our AFN has to be relevant to our people. It has to be responsive to the issues, concerns and needs identified by the people, and it has to be respectful of that diversity. One of the biggest things we’ve done is put ceremony first. Always go back to our ceremonies and traditions and customs and practices. And once you do that and you use the drum for example, all of our First Nations tribes do. There’s one thing that’s consistent. There’s a drum. In all of our nations and tribes from East Coast to West Coast and North, South, not everybody embraces the relevancy of eagle feathers, the sacredness of the eagle. Not all of our tribes go to sundances, not all of our tribes go to sweat lodge. Not all of our tribes go to potlatch, tea dance. There’s diversity.

You have to respect that diversity, But if you use our ceremony, that’s creator’s law. That’s natural law. And it’s important to put that at the forefront. Our worldview is quite simple. We’re two legged. We’re the two-legged. So, when we go to ceremony, we acknowledge the creator. We acknowledge the one that sits in the east, the one that sits in the west, in the south, in the north. We acknowledge our Mother, Mother Earth, and Father Sky, Grandmother Moon, Grandfather Sun. We acknowledge the four-legged relatives we have. We acknowledge the ones that fly, the ones that crawl, the ones that swim. The male plants, female plants. And then we acknowledge those four grandmother spirits that look after the waters, rainwater, freshwater, saltwater, and the power of women when life comes, water breaks. So, we’re the two-leggeds. I don’t care if you’re black, yellow, red, or white. We’re the two-legged tribe and we fit into that family.

We’re all related. We’re all connected.

Policy: And as you leave in terms of gender equity, is there still some work to be done for in the role of leadership? Role of women chiefs at the table inside the AFN? Are you satisfied with the progress that’s being made?

Perry Bellegarde: Women are very powerful and women bring strong leadership at all levels to the table and we embrace that. Even in our ceremonies, half the lodge is male, half the lodge is female. And you have to respect that going forward, there’s always balance and you always work towards that balance in that respect. And you get better decisions.

Policy: How would you like Perry Bellegarde’s leadership to be remembered? In a sentence.

Perry Bellegarde: Bellegarde’s leadership was grounded in our seven teachings—of truth and honesty, love, respect, courage, wisdom, humility. That’s what I’d hope people would say.

Anyway, I campaigned on closing the gap. I’ve used that phrase over and over. According to the United Nations Human Development Index, Canada is rated 6th but if you apply the same indices to First Nations people were 63rd. And that’s why over the last seven fiscal years, I advocated for monies in housing and water and infrastructure and healthcare and education. Investments to close that gap over seven fiscal years. We have close to $43 or $44 billion over seven fiscal years. Again, unprecedented investments to help close the gap. It is very important to recognise that progress doesn’t mean parity.

We still have a ways to go, but we’re moving in the right direction.

From a conversation over Zoom on June 14, 2021