Adapting to the UN’s Distanced Diplomacy, and New York’s New Normal

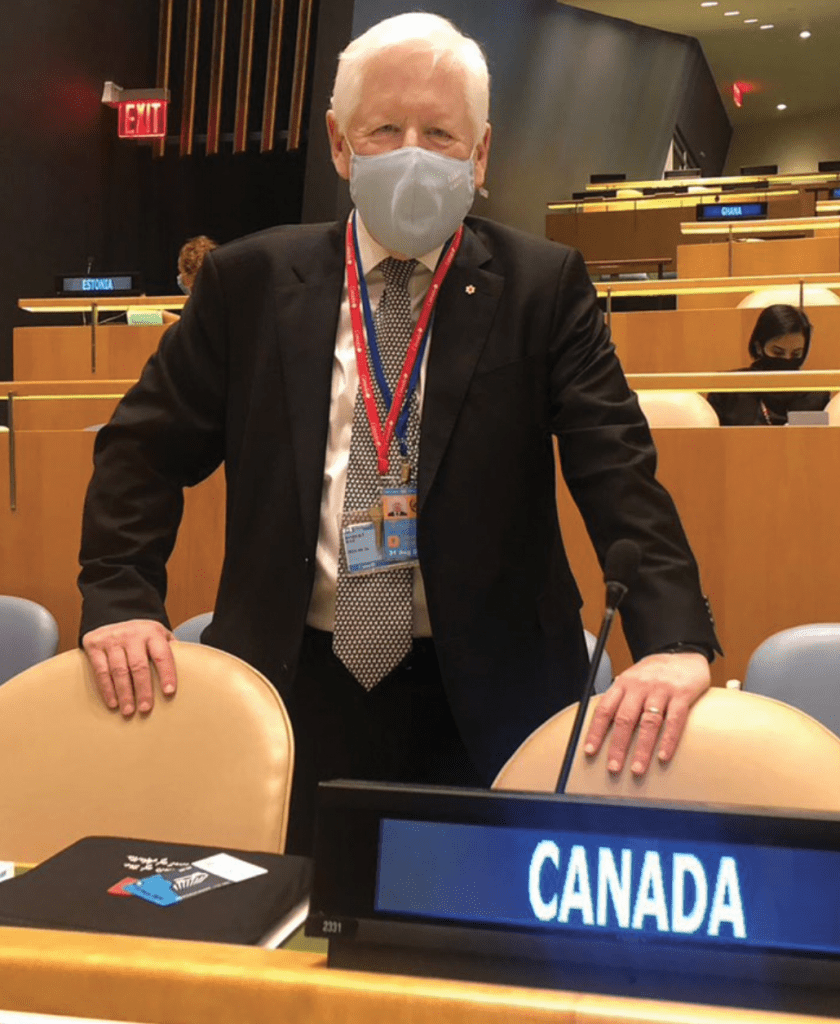

Bob Rae

I had three jobs when COVID came to Canada: teaching at the Munk School at University of Toronto, serving as counsel to the law firm Olthius Kleer Townshend, and advising the government of Canada as Special Envoy on Humanitarian and Refugee issues. This last job was supposed to involve some travel to Africa and Asia, but as February turned to March, it became clear that was not going to happen. Like most people, I had initially underestimated the seriousness of the outbreak, and then it finally hit me, as it did everyone else: Stay home, keep your distance, wear a mask, stay home, keep your distance, wear a mask. And so we did, both confined and liberated by Zoom and other platforms, explaining to grandchildren why we could only talk on the screen and the phone.

Prime Minister Trudeau had asked me at the end of January if going to New York as Permanent Representative to the United Nations was something I could consider. Of course, I accepted, knowing that the appointment would not happen until later in the year. As COVID locked us in, and my work on refugees and humanitarian issues was conducted remotely and virtually, (a strange feeling for an issue that involves such immediacy), the global nature of the lockdown became clearer, and so did the truly global dimensions of the crisis.

Living in a bubble was actually an accurate reflection of the challenge in that first spring. I can remember the joy of the first backyard visit, the first trip to the door of the restaurant to pick up food, and seeing neighbours in the street as Arlene and I went on our masked walks around the block and back home. But as I was experiencing this odd reality—my Zoom life was taking me to refugee camps, to discussions with diplomats, professors, refugees, emergency workers, and in the toughest of settings—I could not help but feel that even as cases mounted in Canada in what we now call “the first wave”, people in most parts of the world were much worse off.

My calls to New York became more frequent that spring, and with the city as the epicentre of the pandemic, I could feel the anxiety talking to UN and Canadian staff working from home with kids in the background. When I talked with civil servants and politicians in Ottawa, the picture in my head was that I was isolated but they were sitting in an office somewhere. It took a while for it to sink in that everyone was working from home, that the empty streets and offices in Toronto had their match in every part of the world as everyone was coping with the same isolation, the same anxiety, the same realities of closed schools and longer dreams and naps.

In July, I worked from the cottage, heading into Ottawa on a more regular basis as the announcement of my appointment meant I had to get ready to head to New York before the UN sessions would start in earnest in September. Expanding bubbles meant children and grandchildren could gather together, and after a multitude of briefings—and yes, more Zoom calls—we packed up the car and drove across the Thousand Islands Bridge armed with diplomatic passports and travel documents allowing us to get to

New York.

We arrived in the evening, warmly greeted by masked staff from the Canadian Mission, and had a meal at a nearby restaurant where a covered sidewalk patio had been built (it’s still there, along with thousands of others), and we slowly made our discovery of New York. It was clear, talking with my colleagues at the Mission, that the spring had been truly traumatic, the night air filled with ambulance sirens as the hospital admissions kept mounting relentlessly (New York lost at least 25,000 people in those early months of the pandemic). Everyone worked from home, and the UN was determined to keep going, and keep meeting, virtually but constantly. I was thrown in at the deep end as Canada was chairing the Peacebuilding Commission and co-chairing, with Jamaica and the UN Secretary General, an ad hoc group of countries assessing the impact of COVID on the global economy.

Both jobs had been started by my predecessor, Marc-André Blanchard, and were to prove both daunting and rewarding in my first year. Some of the fruits of our labours have been well-reflected in decisions by the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the G7, as well as a number of national governments, including Canada.

At a personal level, social life being much quieter than it might otherwise be in New York was actually an advantage. We went to Central Park, to see the Statue of Liberty, to be tourists without being jostled and crammed, and to slowly get to know Canadians here as well as the representatives of 193 countries where face to face meetings were infrequent. Meetings at the UN itself have been largely limited to one per country, distanced, masked, and washing hands.

We are not through this yet. Its health impacts are being felt everywhere, as are the economic consequences. Walking up Madison Avenue twenty blocks and back Arlene and I counted 47 empty storefronts, businesses closed, and the same is true all over the city. It is not a “ghost town”, but it feels the impact still, and this will continue. There will never be “business as usual”, it will be business with a new usual.

Bob Rae is Canada’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations.