Above All, a Transcendent Talent for Friendship: Brian Mulroney, 1939-2024

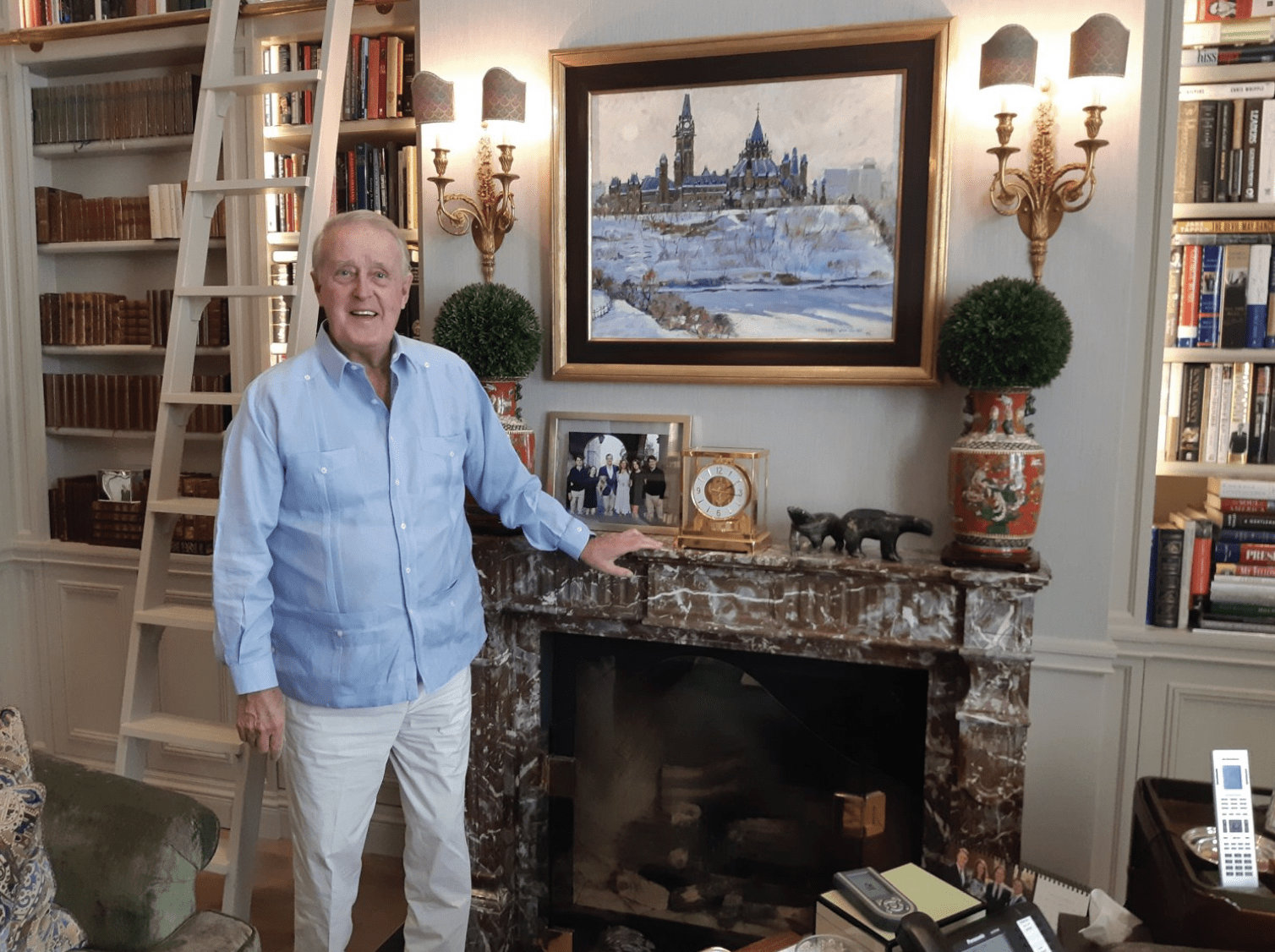

Brian Mulroney in his Montreal home/Gray MacDonald

Brian Mulroney in his Montreal home/Gray MacDonald

By Anthony Wilson-Smith

February 29, 2024

One night in September, 2022, at the Atwater Library in Montreal, the famed cartoonist Terry ‘Aislin’ Mosher was hosting a launch for his book Montreal to Moscow, recalling the 1972 Team Canada-Soviet Union Summit hockey series. Terry’s co-host was Yvan Cournoyer, the legendary ‘Roadrunner’ member of the Canadian team, who wrote the book’s introduction. Another guest, standing quietly at the back, quite content to be a spectator, was Brian Mulroney.

After his own opening remarks, Terry invited the former prime minister and fellow Montrealer to the podium.

Mulroney spoke for five minutes, without notes — equally at home, as always, in both official languages — praising the authors in ways alternately funny, touching, entirely on point, and without a single awkward pause.

After the event, Mulroney offered me a lift to my hotel. On the way, I mentioned that his remarks were particularly gracious given that Terry, by his own admission, mocked Mulroney for years on the editorial page of The Gazette. Mulroney paused, then chuckled. “Yeah, some mornings I cursed that son-of-a-bitch more ways than you can imagine,” he recalled. ‘But you’ve gotta move on – and some of those cartoons were pretty funny.”

There was a time – many years, in fact – when those who knew Mulroney well would have been astonished to hear him so sanguine about past slights. As a negotiator of extraordinary skill, first in business and then politics, he knew how to compartmentalize his feelings and hold his emotions in check in public. But with those he trusted, he could go ‘full Irish’ and openly show his anger. In the later years of his life, he managed the decidedly un-Irish trick of forsaking grudges as though elegantly disposing of excess baggage.

That was striking because Mulroney spent much of his life doing everything – emotions, ambitions, achievements – on an oversized scale. It was one reason so many people were devoted to him and others were not. With his Palm Beach wardrobe, FM radio announcer’s baritone, and endless array of anecdotes, he came across to some as too slick, expansive and, therefore, untrustworthy. He always liked the so-called finer things in life – the most expensive clothes, lifestyle highlights, addresses – and, as soon as he was able, began acquiring them.

The journalist Bob Lewis ran into him in the late 1970s in Montreal one day and asked Mulroney where he was living: he pointed exuberantly toward the wealthiest point of wealthy Westmount and said: “See that hill? Right up on f**king top.”

He had a bad habit, in his early days as an elected politician, of making crowd-pleasing statements that came back to haunt him. Case in point: when he mocked the public service as bloated before becoming prime minister and promised he would give many of its members “pink slips and running shoes.” Not surprisingly, he found an uncooperative bureaucracy when he arrived in the Prime Minister’s Office. He was famous (among journalists) for being an excellent ‘unnamed source’ before running for office himself: he then was astonished and angry when he became the subject of critical stories from those same journalists — often based on leaks from other ‘unnamed sources’ — after he was in office.

But Mulroney’s detractors were often so keen to pile on him that they overlooked his many undeniable strengths. Few people worked harder or more strategically – especially after his marriage to Mila, who brought him, among many things, focus and greater self-discipline as part of an extraordinary life partnership. (That notably includes the crucial decision to quit drinking in the late 1970s, which he told a friend “added four hours” to his already long working days.)

His friends, who drew a protective circle around him, could be found across the country and beyond. He was drawn to smart, talented people.

Mulroney studied both idols and opponents carefully and learned from them. In an informal conversation in the early 1990s on a flight to Africa, I asked who he thought were the most effective opposition MPs. He gave a detailed analysis of several, led by the NDP’s Svend Robinson and the Liberals’ George Baker. In formal interviews, there were two versions of Mulroney. The first, like many political leaders, offered carefully-prepped regurgitations of things said many times before. If, on the other hand, he was comfortable enough to go off-record, things got much more interesting – especially if he started an answer with a couple of four-letter words. Then, you were getting his real thoughts. The most striking element of such conversations was often the extent of strategic thinking that he chose otherwise to keep to himself. His knowledge of specific files was detailed to the point of astonishing. During my time working in corporate communications, I sat in on a meeting with my CEO and the former prime minister. Extemporaneously, he gave a detailed statistical analysis of our business, existing and pending challenges and potential solutions that senior executives with many years in the company would have been hard-pressed to match.

In image terms, Mulroney was blessed and burdened by his Horatio Alger backstory. His rags-to-riches story, with his rise from a tiny, crowded bungalow in Baie Comeau on Quebec’s North Shore to his place in the highest office in the land, with friends in similarly high places around the world, seemed to detractors too good to be true. The problem for his critics is that it really was true, as I discovered on trips to Baie Comeau in which I toured the street where his house had been and interviewed childhood friends still doing blue-collar jobs — many still in touch with him. He was politically courageous in putting forward policies that he knew would be controversial but was convinced were necessary, on such issues as constitutional change, tax reform, and free trade. That extended to decisions affecting him personally. After winning a safe seat in a Nova Scotia byelection in 1983 shortly after becoming the Progressive Conservative Party’s new leader, he took the considerable risk of running instead in the 1984 general election in his hometown Manicouagan riding (which included Baie Comeau). The incumbent Liberal MP, Andre Maltais, was considered effective even by Mulroney. Polls put Mulroney in a distant second when the campaign got underway, and he still trailed at the midpoint. But he was confident he knew the riding well enough – and the voters him – to win. He was right.

The dichotomy between the public perception and the private Brian Mulroney was striking. Some politicians seem open and approachable in public, but keep their private lives (understandably) very much that way: Prime Minister Justin Trudeau comes immediately to mind. Others seem stiff and humorless in public but are far from that in private: the late Quebec premier Robert Bourassa was like that. Some politicians cultivate virtuous, caring public images while being anything but in their private lives.

Mulroney, contrary to the last category, was most beloved and trusted by those who knew him best. His friends, who drew a protective circle around him, could be found across the country and beyond. He was drawn to smart, talented people. The international lawyer Yves Fortier, who helped ease Mulroney’s entry into law practice when he first arrived in Montreal, was, like him, famously charming, successful, flawlessly bilingual, and seen in Quebec circles (including by Mulroney) as a potential future prime minister. He was a Liberal. But when the Liberals came calling for him to run in 1984 with the promise of an important cabinet role, Fortier declined: he did not want to run against his friend. (Mulroney later named Fortier ambassador to the United Nations – one of a series of non-partisan appointments.) The brilliant, often acerbic Stanley Hartt, now-deceased, was one of the country’s top tax lawyers. He abandoned both his lucrative practice in Montreal and his lifelong Liberal allegiance to join Mulroney in office in Ottawa as deputy finance minister, then chief of staff. “I would do anything for that man,’ he once told me.

Any gathering at a Mulroney home – most recently a stunning penthouse condo with a 3000 sq. ft. deck right up on the f**king top of Westmount – invariably included a mix of ‘names’ alongside less-known friends of many decades. That included Quebec cultural and entertainment figures — a community not generally sympathetic to federalist politicians. When I was there in the fall of 2022, filmmaker Denys Arcand was deep in conversation with the grandchildren of an old Mulroney friend. The next morning, Brian and Mila were leaving for a festival in Joliette, Quebec, where they were invited by the headliner, Quebec music icon Robert Charlebois. On the international front, lest anyone forget, Mulroney remains the only world leader ever invited to give eulogies at the funerals of two American presidents – Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush.

The friendships endured because people like Stanley Hartt knew that while they would do anything for Mulroney, the same was true in reverse. When one friend fell suddenly and gravely ill three years ago, Mulroney was a regular presence at the hospital, jollying the doctors and nurses along to make sure they delivered extra care and attention. There are many such stories of Mulroney’s quiet kindnesses – he seldom mentioned them to others – and they don’t always involve close acquaintances. In journalist Roy MacGregor’s 2023 memoirs, he mentions how – after vehemently criticizing Mulroney when he covered federal politics – he received a call from him offering sympathies after the passing of his wife in 2022.

For a long time, even as Mulroney insisted on his satisfaction with life, he still seemed — to me, in any event — to carry a restlessness within. In recent years, that lifted.

As a reporter covering Mulroney for many years and then, for the last 15 years or so, as someone on the periphery of his social and professional sphere, I saw him in various incarnations. He was less than thrilled with some of my coverage in Ottawa in the 1990s, as mutual friends let me know. But by then, he had learned to put aside – or at least disguise – his irritation, and was always courteous. He called when our daughter was born and for years after, in our occasional conversations, invariably asked after her and our son by name. When I was leaving the editorship of Maclean’s magazine – and fulltime journalism, he was my first caller. His key advice, based on his own experience when he left higher office: “Listen to proposals you either never thought you would be interested in, or never thought you would be qualified for.” That played a direct role in several career decisions – all of them good.

Inevitably, Mulroney will not lack for judges of his achievements or failings, in office and beyond. In recent years, his achievements as prime minister — NAFTA, the Acid Rain Accord, his key role in the ending of apartheid and release of Nelson Mandela — drew renewed attention and credit, and he took great satisfaction in that. It reflected the advice he had taken from his great friend, Power Corp. founder Paul Desmarais, years ago: ‘Let your garden grow.’ (Desmarais meant that Mulroney should let his achievements speak for themselves, and they would be fully recognized with the passage of time.)

For a long time, even as Mulroney insisted on his satisfaction with life, he still seemed — to me, in any event — to carry a restlessness within. In recent years, that lifted. He focused even more on family life — always the centre of his universe – with frequent trips to Toronto and beyond to see his grandchildren, or visits by them to see him and Mila in Montreal or their home in Palm Beach, Florida.

We had several long conversations in the fall of 2022 for this magazine in which he reflected on his age and stage in life. Ever since reaching his 60s, he had taken into account the early death of his father Ben at age 62. At the start of each decade beginning in his 60s, he told Mila his goal was to reach the next one – first 70, then 80. On his 80th birthday, he said ‘all bets are off’ – and focused on savoring each day.

Now, for Brian Mulroney, there are no more tomorrows. But as he might have said, with that familiar deep chuckle: yeah, but there were a helluva lot of great yesterdays. And so many people who will remember him, and those, and be thankful. I am one.

Anthony Wilson-Smith is president of Historica Canada and former editor of Maclean’s.