A Primer on Long-term Fiscal Sustainability

In any government fiscal response to any economic crisis, the question of the impact of that response on fiscal sustainability hinges, in layman’s terms, on a combination of assumptions and variables and whether the impact of time on those assumptions and variables will prove to be positive or negative. Fortunately for Policy readers, Mostafa Askari, Chief Economist of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa, has the deep expertise to walk us through the sustainability prospects for Canada’s Budget 2021 response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mostafa Askari

May 10, 2021

The need for a significant increase in government spending in response to COVID-19 and the current government’s approach to fiscal policy reflected in Budget 2021 have renewed concerns about government finances, particularly their long-term sustainability. The phrase “fiscal sustainability” is often used loosely by politicians, media and other commentators. One sees statements like “fiscal policy is unsustainable because the government has been running deficits for the past few years”, or “government debt has doubled over the past five years and this makes fiscal policy unsustainable”. These statements are misleading for the following reasons:

- A government can run budget deficits and, over time, maintain a stable or declining debt as a share of the size of the economy (see below for an explanation of how that is possible).

- The value of debt must be compared to the ability to service and maintain it. In the case of a household, the income of the household is the relevant factor to determine whether the household can service and maintain the debt. In case of a government, debt is compared to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as a debt-to-GDP ratio to assess the importance of its size or a change in its size.

- Fiscal sustainability should not be assessed in the short run.

For the purpose of this article, it’s important to: define fiscal sustainability; review the key economic and finance concepts that are relevant to understanding fiscal sustainability; and examine how fiscal sustainability could be affected by the difference between the rate of GDP growth and the effective interest rate, the size of the primary balance and the size of the current debt-to-GDP ratio. And, finally, we assess the long-term fiscal sustainability of the federal government’s fiscal policy presented in Budget 2021.

The main observation from assessing the long-term implications of Budget 2021 is that the pandemic and government policy decisions have led to considerable deterioration in government finances. The debt-to-GDP ratio will not reach its pre-pandemic level over the next 31 years even under a scenario where trend GDP growth is boosted as a result of the policy measures in the budget. There is a risk that if the assumptions underlying this assessment become less favourable (like a higher interest rate) or the government introduces expensive permanent new spending programs, fiscal policy would become unsustainable in the long run, which could have adverse effects on the credit rating of the federal government. In this discussion of fiscal sustainability, there are several relevant concepts.

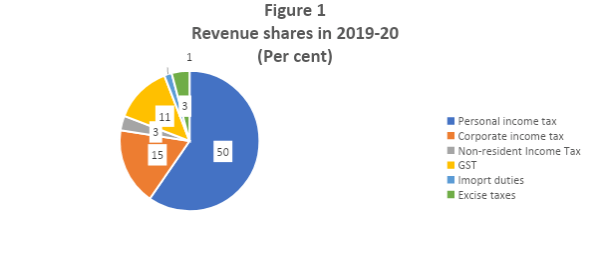

Government revenues: Every year, the federal government receives revenues through personal income tax, corporate income tax, value-added tax (GST), excise taxes, import duties, employment insurance premiums, and interest and dividends from its investment in financial assets.

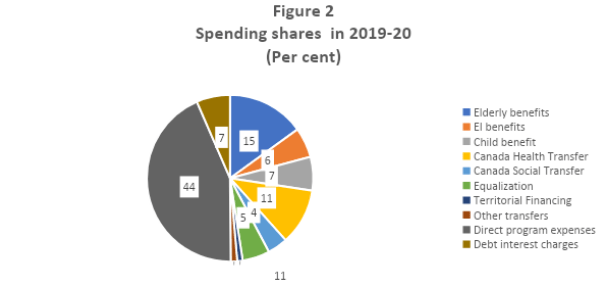

Government spending: Federal government spending consists of: transfers to persons (Old Age Security and income supplement, child benefits, and employment insurance benefits); transfers to other levels of government (Canada Health Transfers, Canada Social Transfers, Equalization, Territorial Formula Financing, and other transfers); Direct Program Spending (budgets of all government departments and agencies); and Public debt interest charges.

Program spending: Total spending minus debt interest charges.

Budget balance: Total revenues minus total spending.

Primary budget balance: Total revenues minus program spending.

Government debt: The government has both liabilities and assets. Liabilities represent the stock of what government owes to other parties at any time. Most of the liabilities are interest-bearing in the form of bonds and treasury bills with different maturities. The interest paid on the liabilities is public debt charges (PDC) that are included in government spending. Government net debt is equal to total liabilities minus the government’s financial assets. Consistent with the Public Sector Accounting Standards, the federal government uses accumulated deficits as the measure of public debt in its official documents. The accumulated deficit is equal to net debt minus non-financial assets.

Public debt (accumulated deficits) = liabilities-financial assets-nonfinancial assets.

|

Table 1 |

|||||||

|

Summary Statement of Transactions – Budget 2021 |

|||||||

|

(billions of dollars) |

|||||||

| 2019–20 | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | 2022–23 | 2023–24 | 2024–25 | 2025–26 | |

| Budgetary revenues | 334.1 | 296.2 | 355.1 | 377.9 | 396.4 | 417.9 | 437.7 |

| Program expenses, excluding net actuarial losses | 338.5 | 614.5 | 475.6 | 403 | 409.2 | 414.4 | 426.7 |

| Public debt charges | 24.4 | 20.4 | 22.1 | 25.7 | 30.5 | 35.4 | 39.3 |

| Total expenses, excluding net actuarial losses | 362.9 | 634.9 | 497.6 | 428.7 | 439.7 | 449.8 | 466 |

| Budgetary balance before net actuarial losses | -28.8 | -338.8 | -142.5 | -50.9 | -43.4 | -31.9 | -28.3 |

| Net actuarial losses | -10.6 | -15.4 | -12.2 | -8.9 | -7.7 | -3.9 | -2.4 |

| Budgetary balance | -39.4 | -354.2 | -154.7 | -59.7 | -51 | -35.8 | -30.7 |

| Financial Position | |||||||

| Total liabilities | 1248.6 | 1,648.4 | 1,799.7 | 1,858.3 | 1,928.0 | 1,983.1 | 2,025.3 |

| Financial assets1 | 435.7 | 472.4 | 466.2 | 459.6 | 473.6 | 488.8 | 496.8 |

| Net debt | 812.9 | 1,176.00 | 1,333.60 | 1,398.80 | 1,454.40 | 1,494.30 | 1,528.60 |

| Non-financial assets | 91.5 | 96.9 | 99.8 | 105.3 | 109.9 | 114 | 117.6 |

| Federal debt | 721.4 | 1,079.00 | 1,233.80 | 1,293.50 | 1,344.50 | 1,380.30 | 1,411.00 |

| Federal debt as a per cent of GDP (%) | 31.2 | 49 | 51.2 | 50.7 | 50.6 | 50 | 49.2 |

What is the definition of fiscal sustainability?

Fiscal policy is sustainable if government debt does not grow continuously and significantly faster than GDP in the long run. Thus, even in the case where the debt-to-GDP ratio rises for a few years, fiscal policy could be sustainable if revenues and spending are structured in such a way that, in the long run, the debt-to-GDP ratio returns to its current level or goes below it. The period over which fiscal sustainability is assessed must be long enough to capture the impacts of the demographic transition that is occurring on the economy and government finances. The change in the composition of population as life expectancy increases and population becomes older will reduce labour force growth and increase cost pressures for the government programs that provide financial assistance to the elderly. Most studies assess fiscal sustainability over a period between 25 to 75 years.

How does debt-to-GDP ratio change over time?

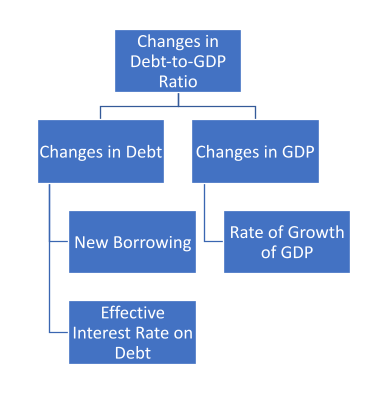

There are three factors that can change the debt-to-GDP ratio: interest rate; new borrowing; and the rate of growth of GDP.

To see how the debt-to-GDP ratio can change over time, we consider three cases:

Case 1: There is no new borrowing required. This means the primary balance (revenues – program spending) is zero. In this case, the level of debt increases only because of the interest that the government must pay on its existing stock of debt that was accumulated in the past. If the effective interest rate is higher than the rate of growth of GDP, the debt-to-GDP ratio increases, and if this continues over time, we have an unsustainable fiscal policy. If the effective rate of interest is lower than, or equal to, the rate of growth of GDP, we have a sustainable fiscal policy.

Case 2: The primary balance is positive (revenues are higher than program spending). In this case, the primary surplus would reduce the stock of debt while the interest on the existing stock of debt would increase it. The net impact depends on the size of these two effects. So, it is possible that even with a primary surplus we experience an increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio if the effective interest rate is significantly higher than the rate of growth of GDP.

Case 3: The primary balance is negative, which means the government needs to borrow money to fund the excess of program spending over revenues (i.e., deficit financing). In this case, debt rises by new borrowing as well as the interest on the existing stock of debt. Thus, if the effective interest rate is equal to or higher than the rate of growth of GDP, we would experience a rise in the debt-to-GDP ratio. However, if the interest rate is lower than GDP growth, the final impact on the debt-to-GDP ratio depends on the gap between the interest rate and GDP growth, the size of the primary deficit and the current size of the debt-to-GDP ratio. This means it is possible to run a primary deficit and maintain a sustainable fiscal policy.

These cases describe the arithmetic behind changes to the debt-to-GDP ratio. They show that whether a fiscal structure is sustainable or not depends on the current and future values of several key financial and economic variables. For example, we may see a rising debt-to-GDP ratio over the medium term, but if government revenues and spending are structured in a way that leads to improvements in the primary balance, we could see the debt-to-GDP ratio declining in the long run, making the current fiscal policy sustainable.

Is the current federal fiscal policy sustainable in the long run?

On April 19, Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland tabled Budget 2021. It is an ambitious budget with almost $135 billion of new spending over the next five years. The budget focuses on helping Canadians cope with the effects of COVID-19 and helping the Canadian economy to recover from the scars of the pandemic. There are also several measures that aim to increase economic growth in the long run. Budgetary deficits are projected to grow in the first three years and then decline over the medium term as the COVID-related spending and economic stimulus spending unwind. Government debt is estimated to rise from $721 billion (31 percent of GDP) in 2019-20 to $1411 billion (49 percent of GDP) in 2025-26.

The sharp increase in spending and government debt has raised concerns about the sustainability of the current fiscal policy. The Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) prepares an assessment of the federal and provincial governments’ finances (using its own medium-term economic and fiscal projections) on a regular basis. Its assessment before the onset of the pandemic showed that the debt-to-GDP ratio at the federal level would continue to decline over a 75-year horizon and that there was fiscal room to increase spending (or reduce taxes) by 1.8 percent of GDP and maintain a stable debt-to-GDP ratio in the long run. In an update of that assessment in November 2020, the PBO showed that the pandemic’s impact on the economy and the resulting rise in government spending had deteriorated long-term government finances. Despite the negative impact of the pandemic, PBO projected that the debt-to-GDP ratio would decline in the long run, albeit at a slower pace than in the pre-pandemic assessment. PBO also estimated that the fiscal room had declined from 1.8 percent of GDP to 0.8 percent. PBO did not include the new fiscal measures included in Budget 2021.

To assess the long-term sustainability of the fiscal policy presented in Budget 2021, we extend the economic and fiscal projections of the Budget to 2095 (see Appendix 1 for a summary of the assumption for our long-term projection).

We also consider three alternative scenarios to assess the sensitivity of the baseline long-term projection to alternative interest rate, GDP growth and spending assumptions. There are other factors that could affect the sustainability assessment. For example, the digitalization of the economy and the redefinition of employment conditions during the pandemic will likely continue and change future labour productivity and economic growth. This could have a marked impact on fiscal sustainability.

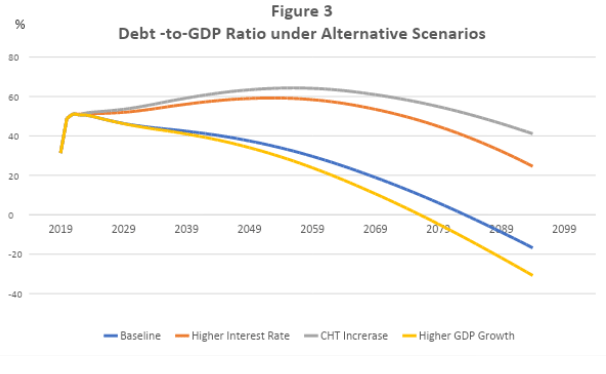

Scenario 1: There is a concern that the significant increase in stimulus spending by the Canadian government and our major trading partners may lead to an overheating of the economy and higher interest rates. In this scenario, we assume that the effective interest rate will rise by 150 basis points relative to the baseline rates over the next six years. As a result, the effective rate will be 4.3 percent in the long run compared to 2.8 percent in the baseline.

Scenario 2: Budget 2021 contained several measures to improve long-term productivity and growth. In this scenario, we assume that those measures will lead to an increase of 0.2 percentage points in long-term trend GDP growth, raising it from 3.8 percent to 4 percent.

Scenario 3: Provincial governments have asked the federal government to increase the Canada Health Transfer (CHT) base by $28 billion. The Budget did not include this measure, but the Prime Minister has said that there will be an increase in the CHT once the pandemic is over. In this scenario, we assume that the CHT base will be increased by $28 billion in 2023-24.

Figure 3 shows the debt-to-GDP ratio in the baseline and under the three alternative scenarios. In each case, fiscal policy is assessed to be sustainable over the selected horizon if the debt-to-GDP ratio returns to its 2019-20 level at 31.3 percent.

Key observations:

- In all scenarios, the debt-to-GDP ratio remains above its 2019-20 level after 25 years, indicating that if we assess fiscal sustainability over a 25-year horizon, the current fiscal policy is not sustainable.

- In the baseline, the debt-to-GDP ratio increases over the medium term due to COVID support and stimulus spending, but it starts to decline in 2025-26. It reaches its 2019-20 level in 2057-58 and continues to decline thereafter, indicating that fiscal policy is sustainable over a horizon longer than 37 years.

- In the higher GDP growth scenario, the debt-to-GDP ratio reaches its 2019-20 level five years earlier than in the baseline scenario, suggesting a slightly improved fiscal prospect.

- If the effective interest rate rises by 150 basis points, the debt-to-GDP ratio does not reach its 2019-20 level before 2090, indicating that we can only consider the current fiscal policy sustainable if we assess that over a period longer than 70 years. This reveals the risk underlying the current fiscal structure.

- If the federal government increases the CHT base amount by $28 billion, the debt-to-GDP ratio will remain above its 2019-20 level even after 75 years, suggesting that the fiscal structure would be unsustainable under that scenario.

We have also estimated the fiscal gap that quantifies how much fiscal actions (changes in spending and/or revenues) the government needs to undertake to achieve the current level of the debt-to-GDP ratio. A positive fiscal gap over a selected horizon indicates that fiscal policy is not sustainable and that to achieve sustainability the government must reduce spending and/or increase revenues by the mount of the fiscal gap. A negative fiscal gap indicates that fiscal policy is sustainable, but the government has fiscal room to increase spending and/or reduce revenues and still maintain a stable debt-to-GDP ratio.

Table 2 shows our estimates of fiscal gap for all the scenarios and three horizons.

|

Table 2: Fiscal Gap |

||||

| Baseline | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 | |

| Higher interest rate | Higher growth | CHT increase | ||

| 25 years | 0.41 | 1.03 | 0.31 | 1.39 |

| 50 years | -0.31 | 0.39 | -0.54 | 0.74 |

| 75 years | -0.88 | -0.07 | -1.21 | 0.18 |

The overall conclusion is that the pandemic and government policy decisions have led to considerable deterioration in government finances. The debt-to-GDP ratio will not reach its pre-pandemic level over the next 31 years even under a scenario where trend GDP growth is boosted as a result of the new budget measures. There is a risk that if the assumptions underlying the baseline scenario become less favourable (as with higher interest rates) or the government introduces expensive permanent new spending programs, fiscal policy would become unsustainable in the long run, which could have adverse effects on the credit rating of the federal government. A sharp downgrade in credit rating, would lead to a higher risk premium on government borrowing and higher debt interest charges.

Mostafa Askari is Chief Economist of the Institute for Fiscal Studies and Democracy at University of Ottawa. He was previously Assistant and then Deputy Parliamentary Budget Officer from the founding of the PBO in 2008 until 2018.

Annex 1

Assumptions for Fiscal Sustainability Assessment

| GDP growth | From 2026-27, GDP is assumed to grow at its long-term trend rate (potential GDP growth) at 3.8% |

| Effective interest rate | It is assumed to be about 1.9% on average over the medium term, gradually rising to 2.84% in the long run. |

| Population projection | It is based on Statistics Canada’s latest projection until 2068. This projection extended to 2095 using simple assumptions. |

| Government revenues | From 2026-27, they are assumed to grow with GDP |

| Elderly benefits | From 2026-27, they growth with the rate of inflation at 2% and the weighted growth of the population aged between 65 and 74, and 75 and over, where the weights are the shares of those age groups in the population 65 and older. |

| Child benefits | From 2026-27, they grow with the rate of inflation at 2% and the rate of growth in the population aged 0-17. |

| Employment insurance benefits | Since the employment insurance accounts must be balanced over time, EI benefits grow with EI revenues from 2026-27. |

| CHT, Equalization and

Territorial Formula Financing |

From 2026-27, they grow at 3% or the average GDP growth over the previous three years, whichever is higher. |

| Canada Social Transfers | From 2026-27, they grow at 3%. |

| New Childcare program | Since the details of how this is going to be structured are not yet known and must be negotiated with provinces, it is assumed it will grow with the rate of inflation at 2% from 2027-28 |

| Direct Program Spending | From 2026-27, it grows with GDP |