A New Third Option for Canada-US Relations

Depending on which leaders were in power in Ottawa and Washington, which bilateral issues lay dormant or erupted as irritants, and what global events and pressures happened to be buffeting the dynamic, Canada-US relations have seen multiple incarnations. Veteran diplomat Jeremy Kinsman looks at what we’ve lived through together, and how we should approach today’s America.

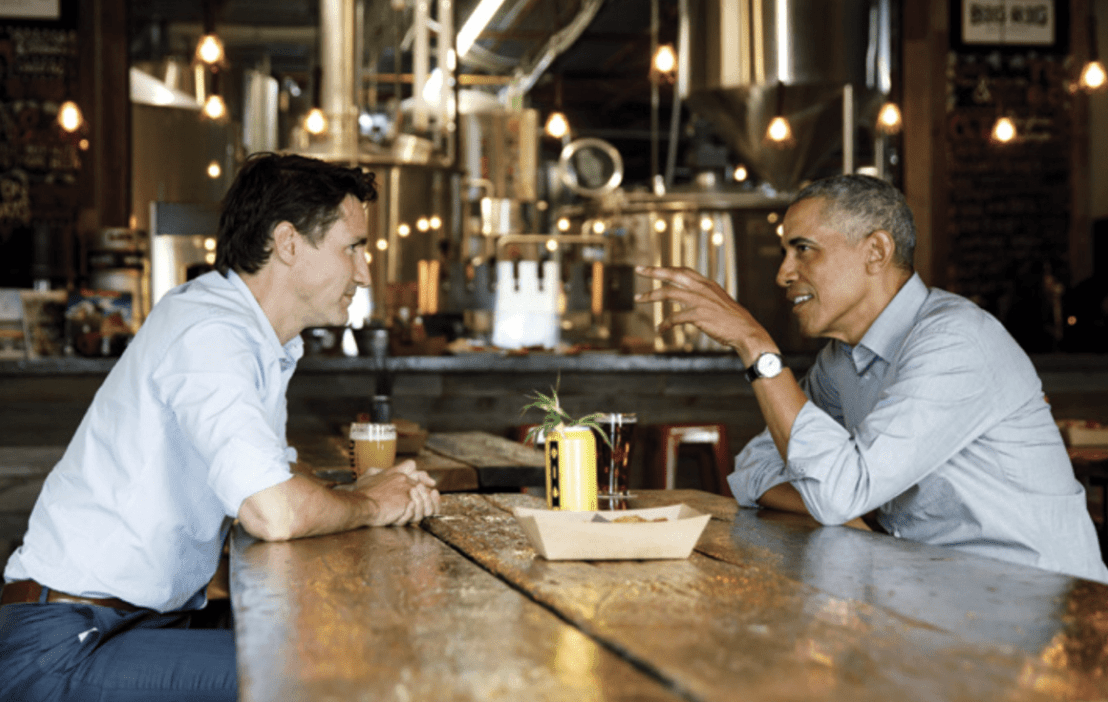

In 2016, Justin Trudeau’s first full year in office and Barack Obama’s last, the two at an Ottawa pub/Adam Scotti

In 2016, Justin Trudeau’s first full year in office and Barack Obama’s last, the two at an Ottawa pub/Adam Scotti

By Jeremy Kinsman

August 27, 2021

Canadians have long spent parts of their lives in the United States without actually living there. Montrealers’ ocean beaches are in Maine; we ski in Vermont, swim in Lake Champlain, and shop in Plattsburgh, easy alternatives to the Laurentians, Eastern Townships, and the local mall.

And, so it went across the country. Ferries carried Vancouver Island hikers and bikers 17 miles across the Juan de Fuca Strait to now inaccessible trails in Washington State’s Olympic Range. Since March 2020, we hike and bike at home. And, once snow birds can again flock to US gated communities and RV parks, even the least observant will register the widening divergence between the two countries.

One half of the US population has become unrecognizable to Canadians and mired in hostility to the other half of Americans. The implications are immense and disorienting to Canadians.

Anne Applebaum put it starkly to CNN’s Fareed Zakaria: “If one half of the country can’t hear the other, then Americans can no longer have shared institutions…we can’t make decisions.”

The nation is riven by partisanship and trust gaps. A Gallup poll from early July showed that: 76 percent of Republicans trust the police, while only 31 percent of Democrats do; 20 percent of Republicans trust the public school system, 43 percent of Democrats do; 51 percent of Republicans trust organized religion, 26 percent of Democrats do. They broadly share a distrust of Congress, the media and the criminal justice system, and a relatively higher level of trust in small business and the military.

The wave of “post-truth” propaganda that accompanied Donald Trump’s accession to the presidency and nearly succeeded in keeping him there by fueling his base and ultimately a mob of radicals has been amplified by the pandemic, contributing to its spread. The presidency of a “normal” politician with half a century of experience at the most senior levels of US governance, including the vice presidency, is facing a hostile resistance targeting not just policy differences but electoral democracy and even the definition of reality.

Canadian confidence in our institutions is much higher, and our antipathies much lower. America’s recent trajectory represents a significant change and, for Canada, a major challenge.

It’s a far cry from 2013, when Diane Francis wrote Merger of the Century; Why Canada and America Should Be One Country. Quoting Franklin D. Roosevelt that Americans and Canadians aren’t “foreigners” to each other, she termed them “siblings” in one family. That was then. Robert Bothwell’s 2015 history of the mingling of Canadians and Americans, Your Country, My Country, also inferred we are essentially one people, offering Michael Adams’ conclusion any gaps are only regional: “in some parts of North America, there is no gap at all.”.Bothwell observes “there is no idea, good or bad, that pops up in the United States that will not find disciples in Canada”—such as Canadians who agree with “the American example of gun ownership or resistance to most kinds of government authority.” Sure, “some” Canadians, but not many.

Our post-vaccination public mood about the US is unlikely to revert to these one-happy-family assumptions. Dr. Noni MacDonald of Dalhousie University, who researches vaccine hesitancy, estimates 5 percent of Canadians are “hardliners who won’t get the vaccine.” But fear of importing COVID is translating to wariness about infection from the political and conspiracy-theory virus polarizing US society. In some ways they conflate: Polls (Washington Post/ABC) show 47 percent of Republicans aren’t likely to get vaccinated compared to only 6 percent of Democrats. The unvaccinated won’t get in.

Even if the good sense of America’s fact-based bare-majority stymies Donald Trump’s return, Canadians should anticipate the gradual default likelihood to a hybrid America, what behavioural economist Daniel Kahneman calls a “regression toward the mean.”

While most Canadians would exclaim “Vive la difference,” they also want to interact with Americans as friends and crucial economic and security partners.

Canadians root for Joe Biden to unite the broken country and re-link it to the great US historical narrative told by Doris Kearns-Goodwin, Jill Lepore, Ken Burns and others. That narrative hit a hairpin curve with Donald Trump’s presidency. But the post-war era, when we shared facts and officials and business people were pretty interchangeable, was already very distant.

As far back as the Vietnam War, things were changing more than we knew. External Affairs’ upper castes backed the US war in anti-communist solidarity. But what Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson saw was US imperialist hubris, heading for a fall. When Pierre Trudeau succeeded Pearson, few in the US expected a charismatic Canadian leader. Unlike those of us who grew up with American sports, TV shows, and politics, the worldly Trudeau showed scant interest. For his only full foreign policy debate in Parliament, in 1981, he titled his legacy speech, “Who Is My Neighbour?” He didn’t mean our literal southern neighbour, but our needy planetary neighbours of the global South.

The review of Canada’s foreign policy he ordered in 1970 lacked a chapter on our most important relationship because officials were ill at ease building risk strategies to plot the management of issues they were used to working out among American friends.

There was nothing friendly about Richard Nixon’s shocking 1971 10 percent tax surcharge on all imports, with no exception for Canada (and no consultation). But the trauma it posed in Ottawa gifted the gist of the missing US policy chapter, the famous “Third Option” (drafted as a one-page memo by External Affairs economic officer David Lee). It aimed primarily to “develop and strengthen the Canadian economy and other aspects of…national life and in the process reduce the present Canadian vulnerability.” Trump’s arbitrary, Twitter-announced tariffs took the vulnerability to a new level, but the impulses of “America First” endure today.

Statist institutions emerged from the Third Option as remedies to give Canadians more control—the Foreign Investment Review Agency, Petro-Canada, and ultimately the National Energy Policy. They were derided and opposed in Washington (and Alberta), especially after Ronald Reagan won the White House in 1980, but provided Canadian diplomats a teachable experience in public diplomacy, pitching “nation-building” narratives to an oblivious US public.

Ambivalence over the relationship lingered. John Holmes was a brilliant Canadian diplomat who exited the Foreign Service because the oafish RCMP persecuted suspected gays, just as they had suspected communists and separatists, and First Nations Canadians. Holmes’ Life With Uncle (1980) urged our “two disparate states,” to forge “an equitable relationship, intricate and complex,” while also acknowledging we needed the United States for the world order we considered essential for our own interests. But even then, he feared agonies fracturing increasingly nationalistic US society, quoting Conservative strategist Dalton Camp’s words on the eve of Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980: “How strange and unfamiliar it is to look on the Great Republic without awe, admiration or envy, but with unease, dismay, and even pity” that rather eerily anticipate our misgivings today.

But golden years intervened. Brian Mulroney and Ronald Reagan created the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement (FTA) in 1987-88, then Mulroney and the first George Bush followed up with the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), including Mexico, in 1992. Holmes had described the US “dream for the world” as one “in which we half believed.” When Mikhail Gorbachev declared the Cold War over, it seemed within reach. Bill Clinton presided over soaring if unequal US prosperity and excess, fuelled by globalization and the digital revolution. But unipolar American self-satisfaction missed the identity-based politics gathering traction.

The 1990s offered Canadian governments unusual creative international influence under Mulroney and External Affairs Minister Joe Clark, and then Jean Chrétien. Lloyd Axworthy led a like-minded coalition to valorize a new paradigm of human security that induced the International Criminal Court, the Ottawa Treaty banning land mines, and the adoption of the United Nations Responsibility to Protect, or “R2P” principle on humanitarian intervention. Finance Minister Paul Martin championed the G20, anticipating the need of inclusive governance for a multipolar world. Such initiatives made US national sovereignty addicts bristle, but Canada-US relationships at the top were never better, validating that Canada can do really helpful internationalist things as a state that don’t involve lining up behind the US, while keeping, even enhancing, our influence there.

Everything changed on 9/11. The thickened US border hijacked the Canada-US agenda. Internationally, the “war on terror” sucked up policy oxygen and budgets. Canada rightly opted out of the disastrous regime-change invasion of Iraq, while George W. Bush’s people fumed. But we joined the “forever war” against Afghanistan’s Taliban that only now, 20 years on, is ending ignominiously with US withdrawal. Canada’s own military and civilian nation-building Afghanistan expedition under the Harper government became virtually the sum total of Canadian foreign policy.

The global financial crash in 2008-09 was an international inflection point. It hurt ordinary people everywhere while exempting the super-wealthy. The world lost confidence in the people in charge. To the Chinese leadership, the crisis laid bare the weakness of Western-style capitalism and US leadership. China reached for its own global influence and impact, archiving Deng Xiaoping’s admonition to “hide our light” and “bide our time.”

While Barack Obama’s 2008 election and stabilization of markets and banking restored US public influence abroad, he faced “white nationalism and racial resentment” at home (pollster Stanley Greenberg).

Canadians adored Obama. So, when Justin Trudeau surfed into his unexpected landslide in 2015, Canada-US prospects seemed again rosy, the PM declaring Canada “back” as a globalist Obama ally for cooperative internationalism.

Trump’s “America First” triumph a year later made it moot. A Cabinet retreat invited private equity Blackstone CEO and Trump ally Steven Schwarzman to counsel on handling the new president. Schwarzman, whose $610.5 million compensation in 2020 illuminates much of what is wrong with America, said “flatter him.” The PMO added taking Ivanka to the theater, sucking up to Steve Bannon, and share-chairing “women and girls” celebrity charity boards.

Trump’s destructiveness surpassed expectations. He came to Canada for the Trudeau-hosted G7 at Charlevoix in June 2018 and kicked US partners in the teeth. Our foreign policy, like Harper’s over Afghanistan, became a single substantive item—saving NAFTA, except that this time Canadian operators under Chrystia Freeland succeeded.

Widespread global relief welcomed Biden’s election. But the toxic disputed aftermath and enduring evidence of a dysfunctionally polarized country keep America’s nervous partners inclined to hedge their forward bets. The defining development of our era is actually China’s rise, now gone sour, particularly in the US. Blocking China’s challenge to America’s primacy is a rare policy thrust both US parties share. Biden seems to fear seeming in any way less than hawkish on China” would compromise political capital he needs for his crucial domestic priorities of recovery.

The intersection of US foreign policy and domestic politics always vexes US partners. As The Economist wrote in July, Washington expects allies to support US determination to “supplement its economic, technological, diplomatic, military, and moral heft.” In short, to enable the US to stay “Number One.” US partners oppose Chinese truculence, coercive behaviour, and human rights violations. But they don’t share Washington’s analysis that China seeks world dominance, that itself makes the world a dangerous place.

Our increasingly assertive security agencies do warn that China is a threat, urging we line up behind our American allies, despite the costly fiasco of blindly doing so over Meng Wanzhou. They want to see defensive vigilance “baked into” Canadian policies across the board.

The Economist warns a drive to de-couple from China “won’t work.” China’s economic success is a reality. China is the principal economic partner of twice as many countries as the US. The US would do better to “defend the sort of globalization that has always served it well.”

Multilateralism is Canada’s specialty expertise. We should valorize this national edge and interest in promoting global rules-based governance and cooperation among our bilateral partners around the world—including in Asia, where we must succeed, and with the third economic giant, the EU.

Shortly after winning the 2015 election, Prime Minister Trudeau met with officers of Global Affairs. Asked how he would show that “Canada’s back,” he said he would build the country’s capacity as a modern economy and an exemplary democratic society, standing for fairness and inclusion.

That is a Third Option for today. We should support it by a permanent public diplomacy campaign in the US that depicts our enduring partnership with America as one of interdependent democracies, jointly engaged in different ways in securing a better world—in hope that America’s “better angels” will prevail.

Policy Magazine Contributing Writer Jeremy Kinsman is a former High Commissioner to London, and former Canadian Ambassador to Moscow, Italy and the EU.