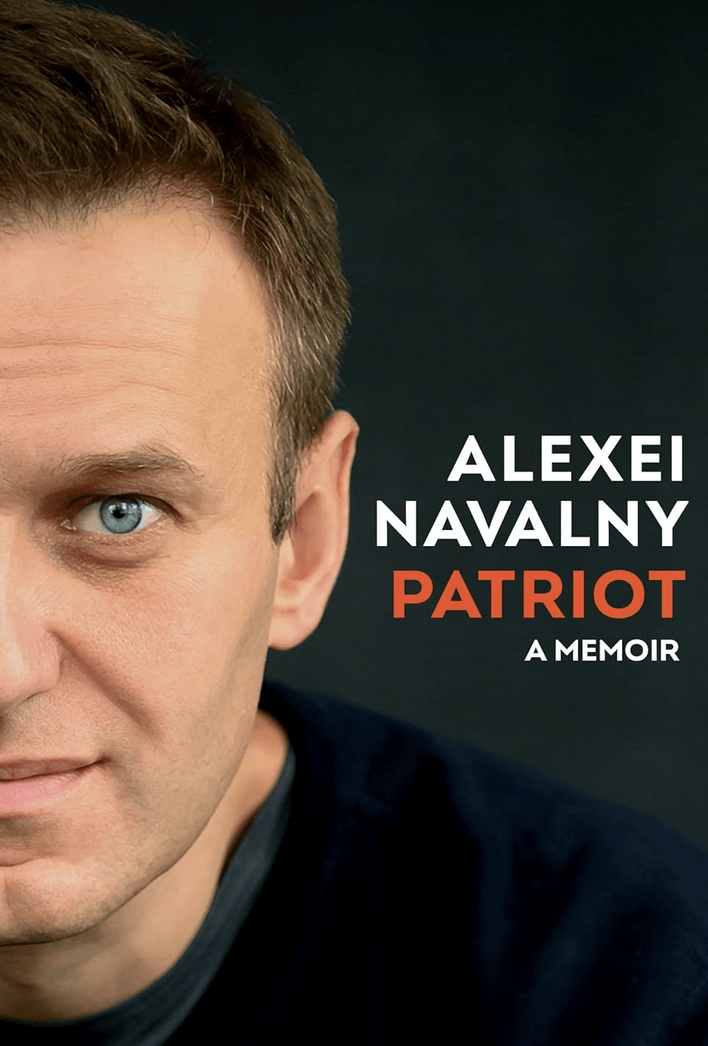

A Legacy of Truth: Alexei Navalny’s Final Act of Patriotism

Penguin Random House/October 2024

Reviewed by Jeremy Kinsman

November 12, 2024

Patriot, Alexei Navalny’s posthumously published memoir, is a compelling chronicle of courage and insight that will, hopefully, be read for generations to come.

The book is the account of Navalny’s rise and fight as a popular and principled dissident against the corrupt regime that tried to eliminate him. His death last February was as dramatic as his life, coming in a Siberian prison, where he had resisted the state’s psychological torture but could not counter the costs of captivity to his physical well-being. The parting segments of this book are written a few weeks before he dies – an end most objective observers have described as murder – after he accepts there will be no escape.

Posthumously published memoirs are scarce. Some great novelists and poets – Kafka, Lampedusa, Sylvia Plath – left behind unpublished manuscripts that became classics. But in nonfiction memoirs, the closest to Navalny’s I can think of is Anne Frank’s Diary of a Young Girl, an innocent victim’s private imprisonment journal, written while hiding from a different, equally monstrous enemy.

Unlike Anne, writing in solitude and in hiding, Navalny was a political protagonist, openly challenging his repressive and corrupt adversaries. He wrote the book describing their attempts to destroy him, to publicize the extent of their crimes, to hasten, if possible, their political demise.

Navalny wrote as a proud Russian patriot. “I just love Russia,” he asserts.”Russia is one of the components from which I’m made.”

Navalny’s goal was to lead the fight to change the regime so that Russia could “become a normal country at last. He recalls that he “once described the beautiful Russia of the Future as a metaphysical Canada: a rich northern country with a low population density, where everyone lives well and is obsessed by philosophical reasoning.”

As he confronted the thoroughly corrupt Russian state of the present, he warned us not to “equate the Russian state with the Russian people,” calling it the “biggest mistake people in the West make.”

He knew what he was up against. In 2015, his democratic ally, Boris Nemtsov, the most popular politician in the country, was assassinated on a bridge outside the Kremlin walls. Navalny was fatalistic, but resolute: “I know one thing for sure: that I’m among the happiest 1% of people on the planet – those who absolutely love their work.”

Publishers crave real-life heroes. Alexei Navalny suited the role perfectly, with his action-packed tale of standing up to Putin’s corrupt, tyrannical security and judicial machine. Navalny’s narrative is indeed in part a combat memoir. But he doesn’t present himself as heroic. He wrote as a normal “dude” who became politicized by the emergence of Putin’s police state, then was compelled to do the right and honest thing, motivated to get again involved in politics by Putin’s appropriation of autocratic nationalism that has “stolen the last twenty years from Russia.”

Navalny at a memorial march for Boris Nemtsov in 2019/EPA

Navalny at a memorial march for Boris Nemtsov in 2019/EPA

Navalny hoped his book would inspire more Russians. If things did turn out badly for him, it could also sustain his loved ones with royalties. “If a murky assassination using a chemical weapon, followed by a tragic demise in prison, can’t move a book, it is hard to imagine what could,” he writes, with chilling prescience. “The book’s author has been murdered by a villainous president, what more could the marketing department ask for?”

He began to write the manuscript when he was in rehab in Berlin after collapsing on a plane from Siberia in August 2020, poisoned by the Russian security service (FSB). He was evacuated to Germany in a coma only after Chancellor Angela Merkel intervened with Putin. As he gradually recovered his faculties, Navalny knew that the regime expected him to stay abroad. It was why he knew he had to return to Russia to resume leadership of his unique organized political challenge against the increasingly fascist regime of Vladimir Putin.

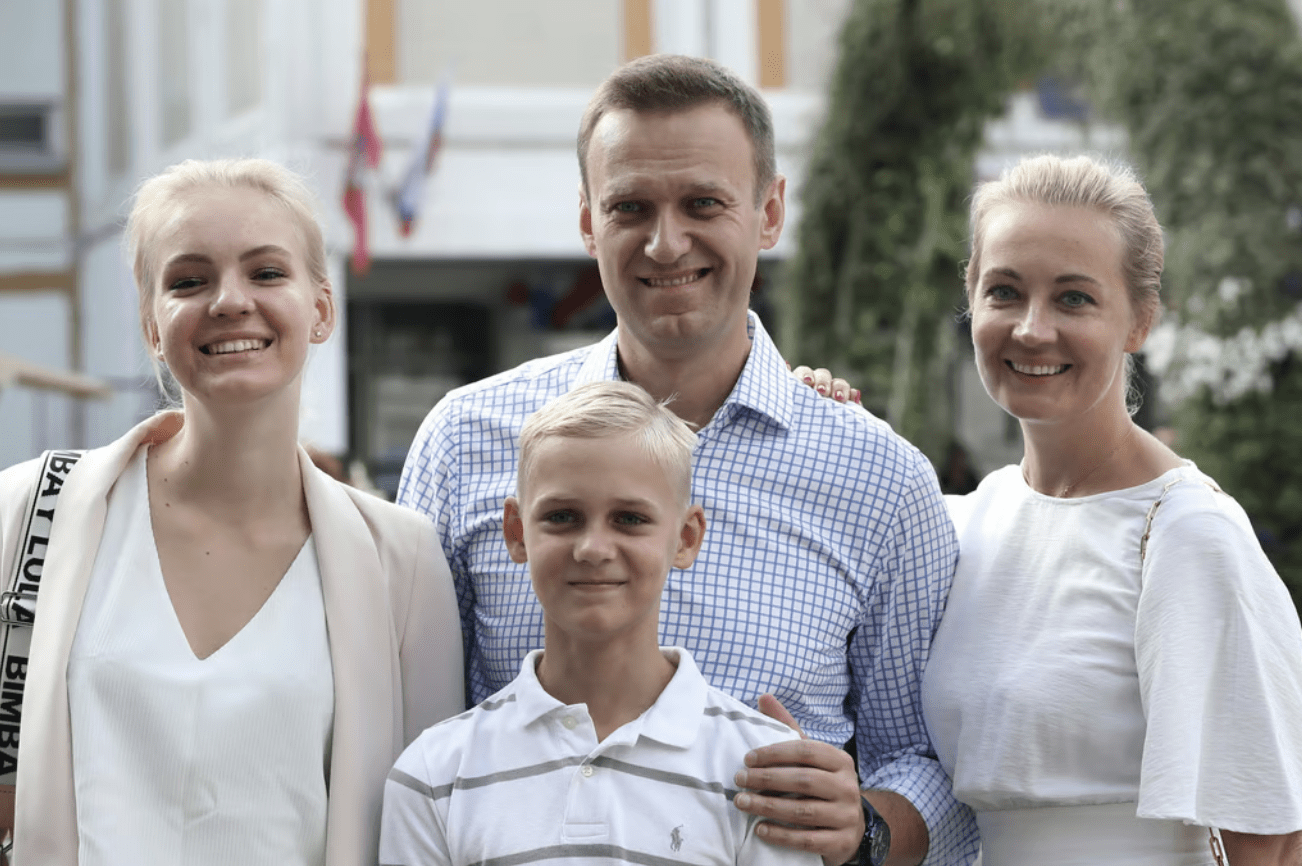

His wife Yulia respected his belief that “the only moments in our lives that count for anything are those when we do the right thing, when we don’t have to ‘look down at the table’ (like the pliant judges who, on instruction, repeatedly condemned him to prison) but can raise our heads and look each other in the eye. Nothing else matters.”

Penned by others, this might be dismissed as grandiose rhetoric. But Navalny meant it, lived it, and died for it.

He never felt destined for such a role. Born in 1976 in Butyn, 50 km west of Russia, to a Ukrainian father and Russian mother, Navalny was still a child when Mikhail Gorbachev announced in 1986 that “we can’t go on living this way,” and launched glasnost, “openness,” which Navalny assessed (and I concurred as Canada’s ambassador in Moscow six years later) would make the USSR “the free speech capital of the world.”

For fairly cosmopolitan Soviet citizens like his parents, who habitually placed a cushion firmly over the telephone to foil surveillance when friends came around for a drink, the reforms Gorbachev introduced were an amazing release from mental confinement. For young Alexei, a self-described “nerd,” freedom of speech and unprecedented access to information became his lifeblood.

His book celebrates glasnost, and Gorbachev’s critical role in hastening freedom in Central and Eastern Europe, and the end of the Cold War. But he bemoans how Gorbachev’s popularity plunged over indecision over the reform process he had launched, ruining the economy and the security of everyday life, creating staggering inequalities, fuelled by insiders’ corruption.

Navlany with his wife, Yulia, and their children in 2019/AP

Navlany with his wife, Yulia, and their children in 2019/AP

Gorbachev’s popularity plunged, accelerated by his attempts to ban alcohol, which had all sorts of unintended negative consequences. Soviet citizens beat back the ham-handed old communist guard’s coup against Gorbachev in August, 1991. But when Gorbachev stepped off the plane that brought him back to Moscow, “everybody knew that a transfer of power to Boris Yeltsin was taking place.” Within months, both Gorbachev and the Soviet Union itself were over.

As he headed to university and then law school, Navalny “unquestionably supported Yeltsin, in all his endeavours,” though with reservations over Yeltsin’s intervention against the rebellious Duma in 1993. I share his memory of Yeltsin beginning his presidency as a galvanizing figure who “sensed the popular mood and how to exploit it.” As the first decade of the Russian Republic rolled on, it became increasingly clear to Navalny that Yeltsin’s “reign was not about reform,” but about “power as a cash cow” for the “bunch of crooks” in his entourage.

Navalny turned in resignation to his quite successful career as a real estate development lawyer. But his political interest would revive, “returned…by Vladimir Putin.”

At first, he joined the conventional democratic reform party, Yabloko, headed by perennial reform figure Grigory Yavlinsky. But he was turned off by the remoteness of its educated membership from ordinary people and their fears and concerns about the effects of change. This was, after all, Russia’s “decade of humiliation.” Isolated by charges he was too much a Russian “nationalist,” he quit Yabloko over the reformers’ inability to connect to ordinary people with a common popular language, resembling critiques of the Democratic Party in the recent US election. Navalny remained a firm believer in talking and listening to everyone.

After a few years getting a degree in finance, and a spell as a visitor to Yale University, which widened his horizons without diluting his Russian patriotism, he created the Anti-Corruption Foundation, which became his movement and the platform for his popularity from which he and his confederates would “act as normal people, hybrids, somewhere between journalists, lawyers, and political activists.” He deferred to the evidence, he had skills, and the magnetism to fill the role as a leader, “someone who is not afraid of the state, and will not accept bribes.”

Navalny’s natural gifts as a leader brought him to the fore in about 2011. He was charismatic, innovative, and witty. He christened the state party of power, United Russia, the “party of crooks and thieves,” and successfully urged millions not to vote for them in the Parliamentary elections of 2011. The Kremlin rigged the results, triggering massive demonstrations of 100,000 in Bolotnaya Square, where Navalny became the galvanizing voice of protest. It was when it had been revealed that Putin was returning to the presidency after the intermezzo of Dmitri Medvedev.

Navalny was swiftly becoming the de facto leader of the opposition. He ran for Mayor of Moscow in 2012, was forbidden access to TV or newspapers, was jailed for part of the campaign, and nonetheless won 27% of the votes. Putin was unnerved by the extent of the popular support. Navalny was never allowed to run for electoral office again.

Navlany during his 2021 show trial/AP

Navlany during his 2021 show trial/AP

He provides a first-hand account of the struggle, and of the hardening tactics of the Russian state to eliminate him and his growing number of followers. It was on a field visit to one of his Foundation’s outpost events in Siberia, that Navalny was poisoned.

Up until his poisoning, he had every reason to believe that the democratic movement he led could ultimately succeed. Putin certainly feared it. That is why he used maximum force to isolate Navalny and at the end, kill him.

He didn’t want his book to become a “prison diary,” but his account of his persecution by the state, their “mean little games,” from systematic sleep deprivation to constant body searches, in an attempt to destroy him psychologically, and certainly to isolate him from the Russian public, is invaluable reading, a profile in courage, and a primer on totalitarian repression. But it is an exciting read, whose zany humour in descriptions of the Russian state’s contortions to break him recall One Flew Over the Cukoo’s Nest.

Over the three years of prison, he tried to shore up his defences through self-discipline, meditation, reading, with the support of his wife, family and millions of supporters. But his health began to suffer. Treatment was repeatedly denied. He undertook a hunger strike, managed still to get his notes out to allies. Eventually, he was cut off from his beloved family, from his lawyers, and toward the end sentenced to 19 years in the most maximum security prison in Russia, an Arctic colony, where he was condemned to punitive solitary confinement for 12 months.

By then, Alexei Navalny had concluded he would die in prison. His formula for dealing with it was to face the worst-case scenario and to look within for faith (he became a Christian), certain that God would “take his punches” for him.

This book, he writes, “would be my memorial,” his record of the struggle to help make Russia a “normal democratic country” that lived by rule of law rooted in justice. He again turns to the dire question he had been trying to answer constantly for three years; “Why did you come back?”

He had “declared everywhere from the stage,” ‘I promise that I won’t let you down, I won’t deceive you, and I won’t abandon you.’ By coming back to Russia, I fulfilled my promise to the voters. There need to be some people in Russia who don’t lie to them.”

A month later, this remarkable, attractive, and charismatic man died, a victim of a grotesque regime that has become perverted by a narcissistic mass murderer who is the chum of the US President-elect.

He leaves behind in bereavement wonderful, dedicated colleagues, and above all Yulia, his family, and millions of believers and supporters, now in exile or in cautionary silence in Putin’s police state. I had thought he would survive and emerge like Mandela did, to lead. It is tragic that he won’t. But sooner or later, whether or not the arc of the moral universe bends towards justice, his example and courage will animate a force more powerful than the clique of despot-servers now running Russia, and similarly, America.

Citizens everywhere should read this book. While they still can.

Policy Contributing Writer Jeremy Kinsman was Canada’s ambassador to Russia, high commissioner to the UK, ambassador to Italy and ambassador to the European Union. He is a Distinguished Fellow of the Canadian International Council.