A Fond Farewell: Brian Mulroney on John Turner

One former prime minister reflects on the passing of another, a one-time opponent he once wanted to name ambassador to the Vatican.

L. Ian MacDonald

September 20, 2020

As the country looks back on the career and legacy of John Napier Turner, who passed away Saturday at 91, it’s impossible not to consider the fact that the most important bilateral dynamic of his life that didn’t involve a family member may have been his political dance with Brian Mulroney.

Over the years from 1984 to 1990, during which the two sparred as leaders of Canada’s “governing” parties, two exchanges between Turner and Mulroney — in the 1984 and 1988 election leaders’ debates — continue to resonate to this day.

The first registered that it was time for a change in 1984 after two decades of nearly continuous rule by the Liberals. The second was the historic debate on the Canada-US free trade deal, the precursor to NAFTA, which transformed Canada into a globally competitive economy.

It speaks volumes about both the character of both men and the times that produced them that Canada’s 17th and 18th prime ministers, implacable foes in both campaigns, became friends for life after both had left politics.

The last time they saw each other, Mulroney told Policy on Sunday, “was just before Christmas in Toronto. We were each having lunch with a friend at the National Club. I went over and said ‘hi’, and we wished each other Merry Christmas. He was slowing down, but he looked fine.”

Beyond their training as lawyers and their square-jawed, leading-man, lawn sign-ready looks, they were very different — Turner an Olympic team sprinter who became a Rhodes Scholar and later a corporate lawyer in Montreal before answering the call of the Liberals to run in the downtown seat of St.-Lawrence-St. George in 1962; then a leadership candidate who insisted he was not running for “some next time” in 1968, when the Liberal establishment chose Pierre Trudeau, before Turner finally became their choice in 1984.

Mulroney, a decade younger, was the electrician’s son from Baie Comeau who went away to St. Francis Xavier for his undergrad degree, and Laval University law school before arriving in Montreal, where he first met Turner in corporate law circles in the mid-1960s. Turner, as Mulroney recalled at the weekend, was then national president of the Junior Bar. He was a rising star at Stikeman Elliott, while Mulroney joined what was then Ogilvy Renault, now Norton Rose Fulbright, two blocks east at Place Ville Marie.

“We saw each other all the time,” says Mulroney, who also recalled gleefully in a CTV interview that Turner “was so good that my mother voted for him” in 1963 in her Montreal riding “before we finally got her switched around” by his own 1984 national landslide.

Chatting by phone on Sunday, Mulroney recalled that when the Gerda Munsinger sex scandal broke to haunt former prime minister John Diefenbaker in 1966, it was Liberal John Turner who got “a couple of us tickets for the House at question period, and escorted us right to our seats in the gallery.” (Years later, it was former minister Turner who jumped into the surf off the Sandy Lane hotel in Barbados, and saved Dief from drowning.)

In the 1984 leaders’ debate, Turner was competing under the influence of an intoxicating post-convention polling bump that seemed to validate all those years he’d spent cooling his heels on Bay Street and the deceptively dormant drag of a ton of political baggage accrued by the party while he was gone.

The perils of that combination became overwhelmingly obvious in the now-classic exchange during which Turner appeared to almost set up Mulroney’s gripping, high-dudgeon comeback by saying he “had no option” but to approve a spate of patronage appointments for the outgoing Trudeau.

As their car pulled away from the CBC studio on the way home to Stornoway, Mulroney leaned over and asked his wife “What do you think happened?”

“The earth just moved,” Mila Mulroney replied.

She was right. In the French debate, Mulroney laid claim to the standing of Quebec’s favourite son. In the English one the next night, the ballot question became time for a change.

Mulroney won the largest majority — 211 of 282 seats — in history, and Turner lived to see another election as Liberal leader.

At Turner’s passing on the weekend, Mulroney described the patronage issue as “the burden” Turner carried in the campaign, the legacy of Trudeau.

The 1988 leaders’ debate was very different, and Turner’s opposition to the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement was no accident of history. He even had the Liberal majority in the Senate force Parliament to sit over the summer of 1988, successfully delaying the FTA implementing legislation going into the fall campaign.

Turner called it “the fight of my life.’ And, as he told Mulroney in the debate: “I believe you have sold us out.’

Turner more than held his own that night. Still, the Liberals lost the election, which returned a Conservative majority, and marked the beginning of the free trade era, with the Canada-U.S. FTA expanded to the NAFTA including Mexico in 1993, to NAFTA 2.0 in 2020, not to mention regional multilateral agreements.

In an opposition sense, Turner successfully defined the issue of the 1988 election as the most consequential campaign of the modern era, and easily the most exciting. He successfully rallied the Liberals, and preempted the claims of the NDP as the logical opponents of free trade. And in an unintended effect, he did Mulroney the favour of waking up the Tories, who had been sleepwalking through the campaign. Mulroney threw away the script, the crowds came out, and the fight was on.

And it was Turner who courageously defined the issue.

But it was all within the bounds of a democratic decision, decency and dignity.

And even in the heat of the 1988 battle, Mulroney was still grateful to Turner for his support of the 1987 Meech Lake Accord, bringing Quebec back into the constitutional fold by recognizing it as distinct society within Canada. Turner did so, despite the vocal opposition of Pierre Trudeau and his testimony against Meech before the Senate in the spring of 1988. Turner said he wanted the Liberals on the right side of history, and saw the unilateral patriation of the Constitution by Trudeau in 1981 as placing them on the wrong side.

For his part, Mulroney never forgot that, even in the heat of the free trade battle. And for decades, Mulroney has said that Turner was one of Canada’s greatest justice ministers, and then a solid finance minister before leaving the Trudeau government in 1975.

After they had both left office, Turner was chairing the annual Cardinal’s Dinner in Toronto, and Mulroney was only too happy to accept his invitation as guest speaker. Mulroney knew what this meant to Turner as a practicing Catholic.

Once while he was still prime minister, Mulroney offered through an intermediary to appoint Turner, by then practicing law again in Toronto, ambassador to the Vatican. Turner declined with thanks. Mulroney then sweetened the offer. “I offered him the Vatican and Italy,” Mulroney recalled Sunday. “And he sent back word that he had to decline, but that he was very thankful for the offer.”

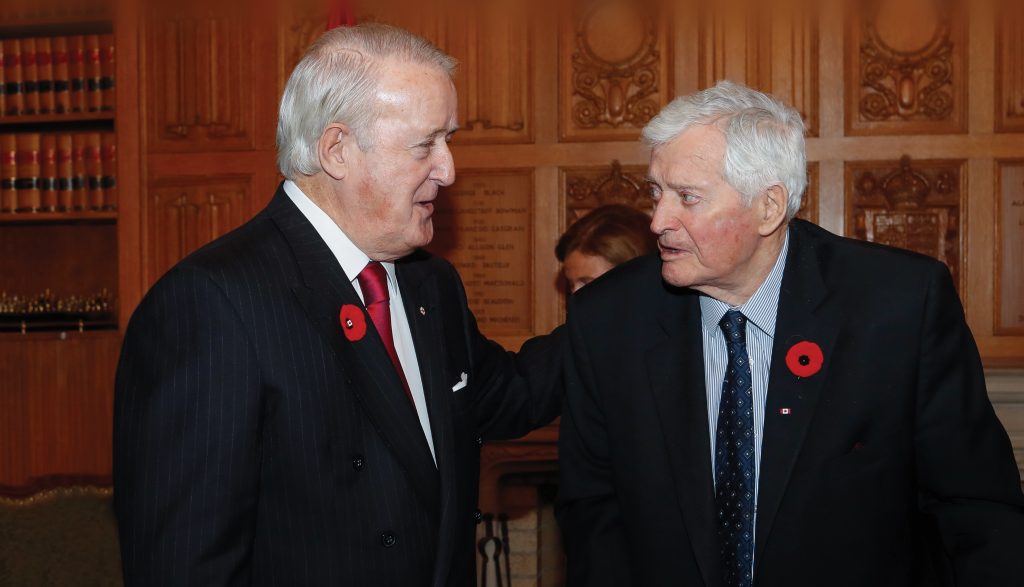

And somehow it was appropriate that Turner and Mulroney sat together when then-Commons Speaker Geoff Regan honoured Canada’s former prime ministers as part of the Canada 150 anniversary in November 2017.

In the case of John Turner, there will be no public eulogies as a normal state funeral is precluded by the social distancing and crowd limitations of the COVID-19 pandemic.

But the outpouring of respect for a man whose fundamental decency was always evident, including from an epic political foe and genuine friend, has been a fitting substitute.

L. Ian MacDonald, Editor and Publisher of Policy Magazine, is the author of the 1984 national bestseller Mulroney: The Making of the Prime Minister.