A Fall Budget 2020 Strategy: Drive Toward the Future

If the 2008 financial cataclysm gave economists a bad name, the health and economic implications of the COVID-19 lockdown have generated demand for all the expertise and ingenuity they can muster. As former Parliamentary Budget Officer Kevin Page writes, Canada urgently needs policies to address long-term issues such as climate change, income disparity, economic and health resiliency and competitiveness.

Kevin Page

It is a safe assumption that government of Canada cabinet ministers and Finance Department officials have spent much of their summer thinking about an economic recovery plan for Canada and a fall budget.

The political and economic stakes are high. With the prorogation of Parliament, triggered in part by the resignation of a finance minister, the government will table a Speech from the Throne in late September.

This will be a vote of confidence. If the government fails, we are headed to a fall election. If the government succeeds, Parliament and Canadians will push for a fall budget to ensure words turn into deeds.

This will be a vote of confidence. If the government fails, we are headed to a fall election. If the government succeeds, Parliament and Canadians will push for a fall budget to ensure words turn into deeds.

While I’ve been reading spy novels, they are looking over the shoulders of colleagues in the European Union and possibly US presidential candidate Joe Biden to see what they are planning for recovery. They are assessing recently announced provincial (e.g., Ontario and Alberta) and municipal recovery plans. They are reading geeky disquisitions on possible economic scenarios for the world economy—with and without a vaccine—and trying to find a governing philosophy for fiscal policy in a world awash in debt.

If our political leaders and my former public service colleagues get a chance to read one spy novel before the frost hits the ground, I recommend The Paladin, by David Ignatius. In a period of great difficulty, the principal character tells himself to ‘move’.

When the present collapses into the past, the only path of escape is to drive toward the future. When you don’t understand a problem, that means you haven’t gathered enough information.

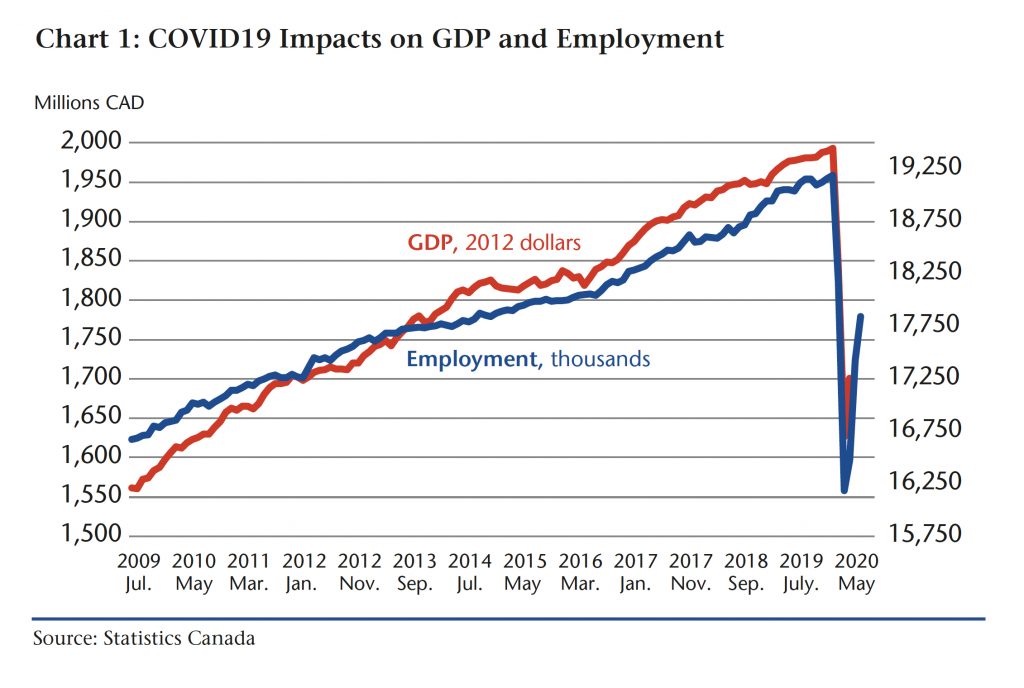

To state the obvious, the current public health crisis and the scale of economic fallout from containment measures is unprecedented. We have not experienced declines in output and employment of similar magnitude since the Depression in the 1930s (Chart1). If we rely on past (stimulus-type) policies to guide economic recovery plans they will likely be misguided and fall dangerously short. We cannot collapse present policy thinking into the past.

Economic planning scenarios in the future will center on a range of epidemiological outcomes for COVID-19 (i.e., vaccine, no vaccine; number and size of waves of infection) and individual country and global health and economic policy responses. Gone is the focus on one baseline scenario. Gone is the assumption that individual countries can pretend to isolate themselves from what is happening elsewhere.

Plans are required for multiple scenarios. Uncertainty cannot be an excuse for no plans. As the saying goes, “No plan, no action leads to no results”.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) suggests that countries should think of at least four phases of policy responses: 1) immediate (Canada is beyond this stage); 2) cushioning impacts and preserving capacity (ongoing); 3) recovery; and 4) resilience and debt management. The transition from phase 2 to 3 will not be “linear and smooth”. Different industrial sectors and people will not get to the recovery phase at the same time.

As somebody who worked in an auto garage during high school and learned to drive in an old tow truck (1950s Ford) with a standard transmission—can you ride the clutch without causing harm to the transmission? Do you have a choice, when you’re starting on a hill? In economic speak, there are costs to living with more debt. Debt finance is the economic transmission fluid.

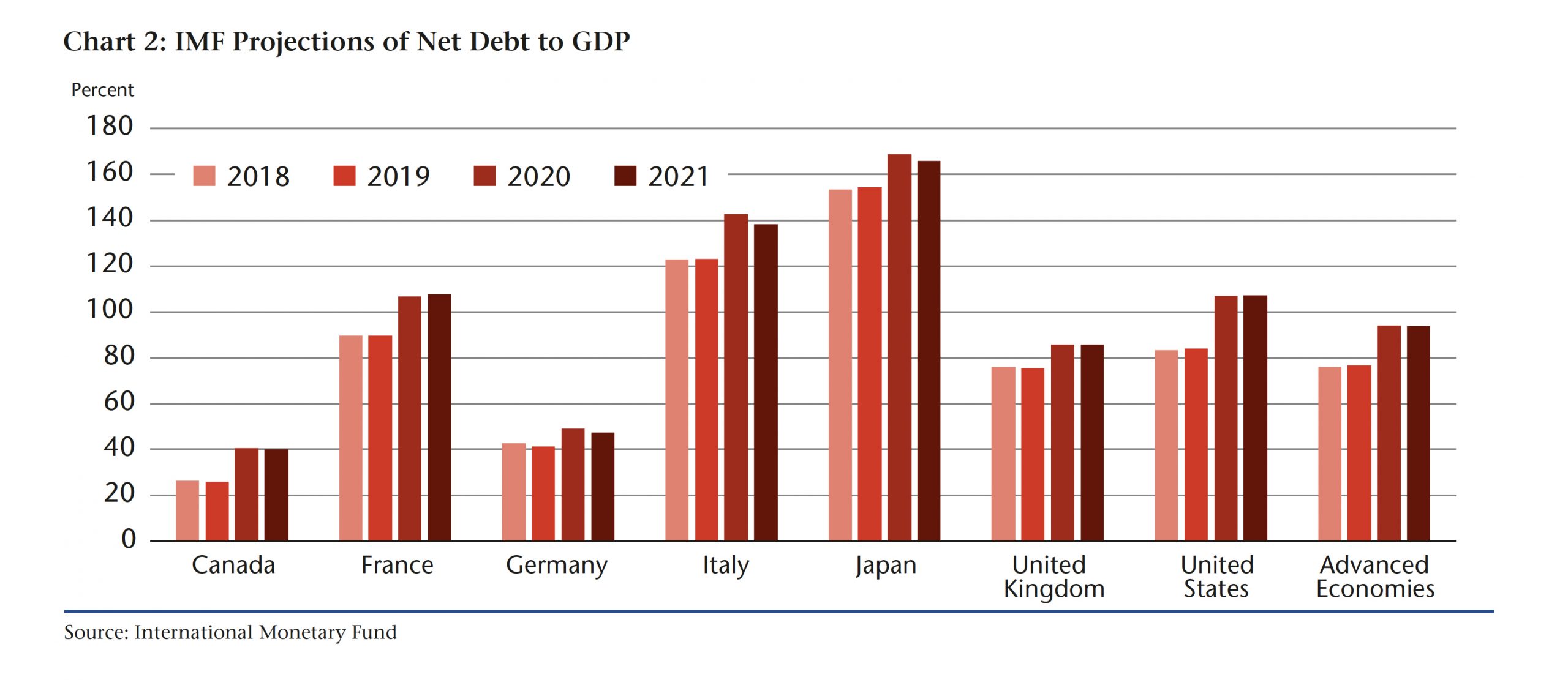

Fiscal and monetary policy are (have been) headed into uncharted waters. Since the 2008 financial crisis, terms like “quantitative easing” are becoming commonplace in the speeches of central bankers. Central banks are working with governments (putting government debt on bank balance sheets) around the world to ease the burdens of governments going to markets to raise money. While some will argue correctly this is not new, the amounts are setting records.

The economics of deficits have changed. With next-to-zero interest rates and no inflation in near sight, there are virtually no bottom-line balance sheet impacts of running larger deficits. All the risks are punted to the future. Debt creates instability risks. If years down the road, inflation makes a comeback, interest rates will rise. The carrying cost of debt will skyrocket. Higher debt interest costs will crowd out spending on key policy priorities.

The pressure is on finance ministers to explain the trade-offs and risks of deficit finance to Parliament and Canadians and the evolving role of our independent central bank. The pressure is on macroeconomists to give us a new governing philosophy for fiscal and monetary stabilization policy.

The pressure is on finance ministers to explain the trade-offs and risks of deficit finance to Parliament and Canadians and the evolving role of our independent central bank. The pressure is on macroeconomists to give us a new governing philosophy for fiscal and monetary stabilization policy.

How do policy makers transition from fiscal supports essential to help households and businesses during containment and re-opening phases to a post-COVID world, given the prospects for a weak, drawn-out and uneven recovery?

Targeted policies are essential. The process has started with the evolution of programs like the wage subsidy and employment insurance. With high but declining unemployment rates and no vaccine in sight, expect this to continue but with increased focus on people and businesses locked out of the recovery.

As McKibben and Fernando (CEPR, 2020) point out in a recent paper assessing prospects for different COVID-19 economic scenarios, “Withdrawing macroeconomic support and creating ‘fiscal cliffs’ through setting expiration dates on critical fiscal support policies in economies is likely to worsen the uncertainty and increase economic costs.”

Should policymakers focus on long-term goals as they develop COVID-19 economic recovery policies? Yes.

The European Union has already launched its recovery policy path to the future. They have recently agreed to a trillion dollar plus (Canadian) recovery fund. The policy framework is composed of five big missions—cancer, climate change, oceans, cities, and food. The missions are designed to bring evidence, resources and policy experimentation to long-term issues. Targets will be set—along the lines of President John F. Kennedy’s 1961 vow to put a man on the moon by the end of the decade.

US Presidential candidate Joe Biden will campaign on a long-term recovery policy “Build Back Better”. The high-level plan focuses on four long-term challenges—manufacturing, infrastructure, children, racial equality. While financing the challenges will depend on a presidential victory and congressional backing, the Democratic candidate is proposing government support well in excess of a trillion dollars.

In Canada, policies to address long-term issues such as climate change, income disparity, economic and health resiliency (i.e., our capacity to address the next policy shock, whether a pandemic or financial or geopolitical crisis), and competitiveness are urgently needed. Governments need to lay out a vision (a north star) and plans to build confidence and partnerships (investment). Why not pro-actively shape and drive our future—more sustainable, more equitable, more resilient, more digital.

I hope that over the summer and early fall that cabinet ministers and finance officials spend some time reading EU documents and US presidential campaign materials and maybe the odd spy novel like The Paladin. If they do, maybe the economic recovery strategy will be focused on long-term challenges. We can use a Canadian version of the “missions” approach to generate the evidence, collaboration, and policy experimentation to hit defined targets.

If we are going to use deficit finance to dig our way out the economic hole created by COVID-19 then it is essential that spending is future-focused to help the next generation. In a Canadian context, the EU/US long-term fiscal stimulus would be well in excess $100 billion over the next five years. This number might have been inconceivable a few years ago, but not now in the context of an estimated decline in GDP of 7 percent in 2020, millions of Canadians out of work, and a record increase in the estimated federal deficit to $340 billion. If our competitors can afford it, can we afford not too when our public finances are in better shape?

Contributing Writer Kevin Page, formerly Canada’s first Parliamentary Budget Officer, is founding President and CEO of the Institute for Fiscal Studies and Democracy (IFSD) at University of Ottawa.