Requiem for a Rebel: Lessons in Power from the People’s Pope

Pope Francis meeting with fellow status-quo disturber Whoopi Goldberg in October, 2023/Vatican Media

Pope Francis meeting with fellow status-quo disturber Whoopi Goldberg in October, 2023/Vatican Media

By Lisa Van Dusen

April 28, 2025

“Anyone who wants to be pope doesn’t care much for themselves. God doesn’t bless them. No, I never wanted to become pope.”

Pope Francis

The notion that the worst popes are the ones who want it the most is now so embedded in papal lore that one imagines the conclave set to begin on May 7th to name a successor to Pope Francis as a game of geriatric, performative hot potato, with cardinals diving under desks and insistently waving off entreaties just to pass the balkiness test.

But in the case of the former Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio, the reluctance seemed entirely authentic. During the response quoted above — to a question asked at a 2013 Vatican Q&A by a Jesuit schoolgirl who looked thrilled at his answer the way children are always thrilled when they’re offered the truth instead of a platitude — he seems genuinely, hilariously nonplussed as to how he ever got himself into this gig.

Indeed, the reasons why any (until further notice) man would actually want to be a pope instead of a priest have mostly to do with wealth and power, and he had a longstanding aversion to both that defined not only his papacy but his life.

As the world said goodbye to Pope Francis this weekend, that relationship to power was at the heart of the responses from people — Catholic and not, Christian and not, believers and not — explaining why they were so moved by both his life and his death.

“I hope we get another pope as skilled as Francis at speaking to people’s hearts, at being close to every person, no matter who they are,” Maria Simoni of Rome told The Guardian while queuing Sunday to pay her respects at the late pope’s tomb.

To the extent that it was possible, Pope Francis eschewed the trappings of privilege, declining what most people protected by wealth consider the perks: the luxuries (the bespoke, red Gucci loafers and papal limousines of his predecessors replaced by plain black lace-ups and a Ford Focus); the comforts (the papal chambers in the Apostolic Palace relinquished in favour of the more communal space of the Santa Marta guesthouse); the sequestration from the sounds, sights and smells of life among human beings outside the cocoon (he didn’t just wash the feet of prisoners and migrants, he kissed them).

It wasn’t that he renounced the power of the papacy altogether. He just used it to do things that most people wouldn’t have, and most popes hadn’t. He had one of the two most powerful public platforms in the world, and he frequently used it to target the power of the church in his role as an advocate for the people.

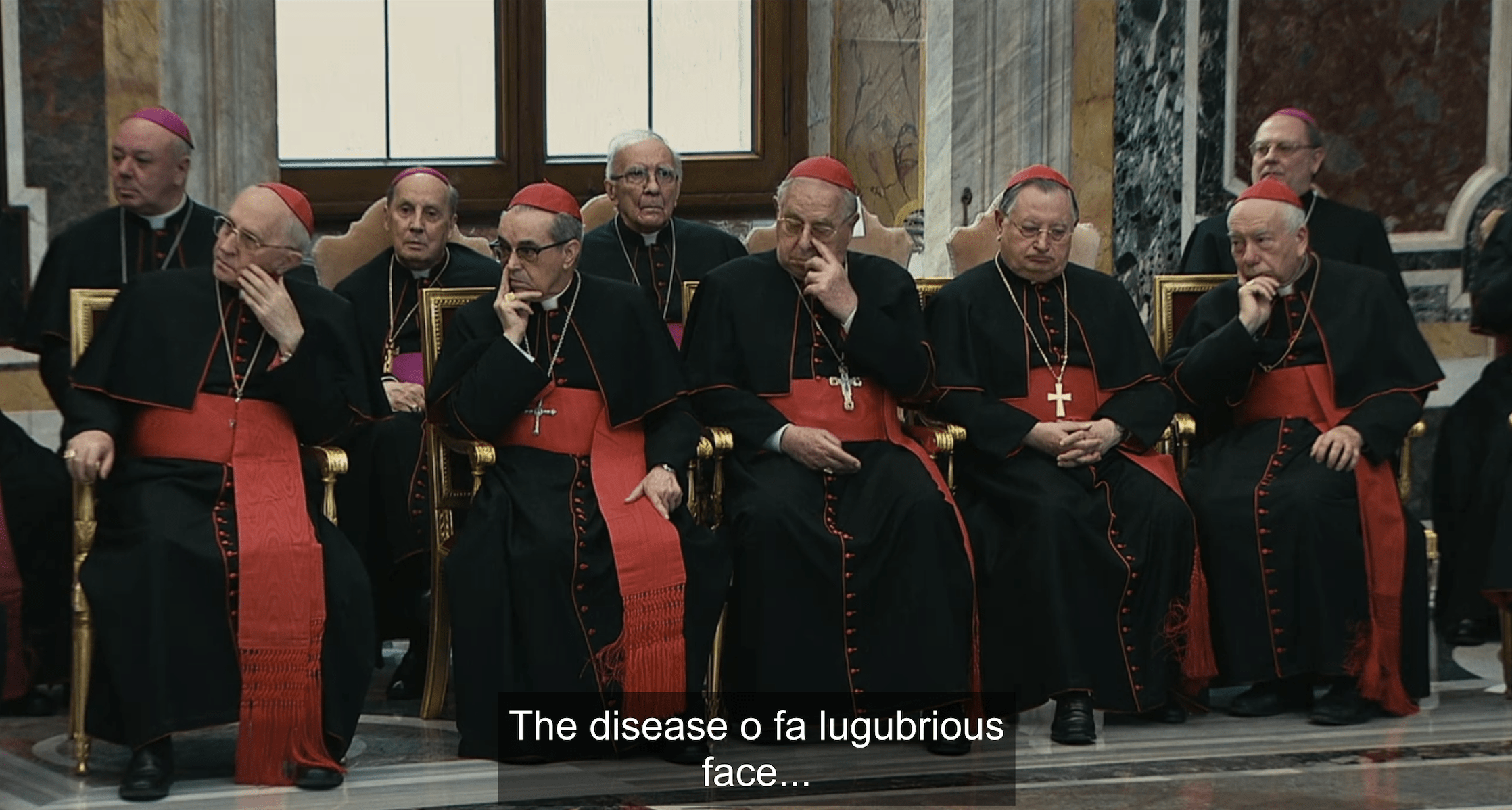

The curia as Pope Francis bemoans their lugubrious faces (subtitle glitch Prime’s/Screencap

The curia as Pope Francis bemoans their lugubrious faces (subtitle glitch Prime’s/Screencap

One priceless example of this can be found in the well-reviewed 2018 Wim Wenders documentary Pope Francis, a Man of His Word (now streaming on both Netflix and Prime), during the clip from Francis’s 2014 annual Christmas address to the curia, delivered in the form of a diagnostic list of diseases afflicting the church, from “mental and spiritual petrification” to the “existential schizophrenia” of hypocrisy to “gossiping, grumbling and backbiting”. By the time he bemoans “the disease of a lugubrious face”, his audience looks like a modern Da Vinci mural of lugubrious faces (above).

The framing of humour as something almost sacred was evident in his citing that day of the prayer of St. Thomas More (“Grant me, O Lord, a sense of good humour…”), and in the first-ever “comedy conclave” or “blessing of the wiseasses” in 2024, at which Pope Francis invited 100 comedians to the Vatican. As a form of rebellion in a world largely besieged by powerful men gone mad, he seemed to wield his laugh as an infectious weapon against despair.

That use of good power to subvert bad power — of love against hate, truth against lies, openness against exclusion, solidarity against inequality, humour against lugubrious face — made him the people’s pope because these were all conscious, active choices made daily by a man who could have much more easily made different ones but didn’t, and the world knew it. It was the same quality that annoyed his critics.

Pope Francis apologized to Canada’s Residential Scghools survivors in April, 2022/Reuters via Vatican pool

Pope Francis apologized to Canada’s Residential Scghools survivors in April, 2022/Reuters via Vatican pool

“It is not right to accept evil and, even worse, to grow accustomed to evil, as if it were an inevitable part of the historical process,” he told Canadian Indigenous leaders and Residential School survivors at the Vatican in April, 2022, situating himself firmly on the side of all victims of all abuses of power, committed by the Catholic church and otherwise.

Above all, he told the truth, which gave him a moral authority that transcended the title. He told it unscripted and uncoached, like a walking embodiment of the Mark Twain quote that if you tell the truth, you don’t have to remember anything; like he was congenitally incapable of lying or even embellishing for the sake of propriety. It’s why sentences like “Who am I to judge?” as his response to a question about LGBTQ rights carried so much weight. It wasn’t code, it was leadership. It’s why he cited Catholic catechism to back up that quote as a rebuke to everyone who distorts scripture to rationalize their prejudices.

Even when reading from a text, Francis was a face-value messenger in a world addled by Orwellian doublespeak and tactical mendacity. He must have driven the Vatican press and comms staff crazy until they, presumably, gave up and decided they had no choice but to let Francis be Francis.

“He believes he communicates with his language, with his spontaneous, non-institutional communication,” veteran Vatican correspondent Valentina Alazraki said last month. “And the press office reflects the Pope’s desire to be the one who communicates.”

And if consistency is the better part of branding, everything he communicated, from what he wore to what he preached to what he wrote, fit into a worldview that favoured fundamentals over doctrine and love of humanity over dogma. The pope who projected video depicting the ravages of climate change onto the facade of St. Peter’s during the Paris COP21 — six months after publishing the encyclical that established him as a world leader on the subject — was neither a passive observer nor an ideologue. He was a humanist.

That fact was evident in every moment he lived out in the world, including in his interactions with individual human beings and in every act of elevating their value above the fleeting perversions of political power, from his visits to Yad Vashem and Auschwitz to his nightly phone calls to the only Catholic church in Gaza.

At a time when human beings are being divided, misrepresented, disenfranchised, economically marginalized, misled by propaganda, and weaponized against each other in unprecedented ways, that made Pope Francis more than a figurehead and the truth he told more than just messaging.

And, as the head of a church itself weakened by the abuse of both human beings and of power, he set an immortal example for how to treat both.

Policy Editor and Publisher Lisa Van Dusen has served as Washington bureau chief for Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, senior writer for Maclean’s and as an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.