Canada and Trump II: Navigating an Increasingly Dangerous World

January 15, 2025

To the extent that foresight is possible in today’s world of interconnected crises, it seems a fair bet that post-inauguration Donald Trump will continue to stir chaos and destabilization, especially for Canada. It’s in his nature as a power player, and in his technique as a negotiator. Trump’s is not a “win-win” negotiating approach, it’s winner-take-all.

It makes the advent of his second term almost universally troubling for US democratic allies, partners, and neighbours, although major non-Western governments seem to welcome his return, notably India, Brazil, Saudi Arabia, and, of course, Russia and China.

While we survived Trump’s first four years in office, he now poses a greater threat to both Canada and the world.

Trump’s unilateralism scorns the multilateral rules-based order created in the aftermath of World War Two. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine brought land war back to Europe, disabling postwar norms of international behaviour and recreating Russia-Western hostility. Trump’s personal belligerence accelerates an arms race on which China and Russia are already embarked. International safeguards have checked use of nuclear weapons since Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but global control systems are weakening, inviting a catastrophic mishap.

The peril of climate change is obvious, but, evidently, not to Trump. In the absence of American leadership, prospects of attaining vital global climate stabilization goals are already dimming. During 2024, the “year of elections” in which more than half the world’s populations went to the polls, climate change sank as an electoral priority almost everywhere, at least as a short-term economic priority.

Back in the 60s, Bob Dylan caught the generational shift in the American zeitgeist when he wrote the protest anthem, The times, they are a-changin. With Trump’s re-election, the pendulum of change and protest has swung back. Major US banks have delisted as supporters of the UN “net zero” climate initiative to diversify away from fossil fuels (headed up by UN Special Envoy for climate action and all-but official Liberal leadership contender Mark Carney), in order to avoid offending the incoming president whose “drill, baby, drill” enthusiasms run entirely in the other direction.

The progressive agenda successfully and pejoratively re-cast as “woke” has also bitten the dust, with widespread corporate and institutional ditching of “DEI” pledges for employment diversity, in line with recent US Supreme Court decisions against longstanding affirmative action practices.

Another attitudinal shift that accompanies Trump’s inaugural is the pseudo-legitimization of an “alternative facts” parallel reality that has migrated from blatant propaganda into the larger communications sphere. Mark Zuckerberg’s climbdown from fact-checking for Facebook means that the facts and the scientific method for establishing them exist on a par with anybody’s intuitive or selective “truth.” Meanwhile, Elon Musk, Trump’s alpha-male propagandist, freely and falsely trolls allied democratic leaders while unacceptably rooting for their right-wing populist opponents.

These crucial disruptions add to discomforts in almost all democracies, whose elected governments have strained to deliver satisfactory outcomes for angry, polarized, and distrustful citizens influenced by exacerbating disinformation from ubiquitous social media, which will now be more unchained than ever.

Democracy itself isn’t in retreat as an ideal, but is on the back foot in practice. Incumbent democratic leaders are under fire, partly for not leading enough in an atmosphere of chaos often curated precisely to confound leadership. Authoritarian demagogues promise easy answers to complex problems, often citing bogus precedents and fictionalized history. Frustrated citizens, especially young men seeking validation in the most dubious role models, lap it up.

Another attitudinal shift that accompanies Trump’s inaugural is the pseudo-legitimization of an ‘alternative facts’ parallel reality that has migrated from blatant propaganda into the larger communications sphere.

Ezra Klein of the New York Times evokes the “unsteady, unpredictable emergence of a different world” in which “much that we took for granted in the last 50 years is breaking down.” Making nations “great again” reveals a distrust of a cooperative future in shocking contrast to the global euphoria that reigned after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and the end of the Cold War. The optimism of the rollicking 1990s now seems aberrational. Its appearance of cooperative global consensus around open government and markets led by the US has been progressively undermined.

The eternal human factors of mass psychology and false assumptions became aggravated by disruptive events that unfolded after the internet made mass psychology a captive target and false assumptions contagious: 9/11 and subsequent terrorism, the “forever wars” of Afghanistan and Iraq; a financial cataclysm catalyzed by mass deception; the roller coaster of hope and disillusion of a failed Arab Spring; and the propaganda hangover and debilitating epidemiological long tail of the global pandemic. Trust in institutions and governments fell as nationalism rose.

Trump himself quipped last month that the world has “gone a little crazy”, ironic given his musings that the US should annex Canada, colonize Greenland and grab the Panama Canal. While debate continues whether the US under Trump will be simply nationalistic, unilateralist, isolationist, or interventionist, Canadians begin to fear that Trump’s impulses seem decidedly imperialistic. His threat to deploy “economic force” to persuade Canadians to join the US as the “51st state” takes the incredibility cake in Canada.

Benjamin Labatut’s 2020 book, When We Cease to Understand the World, situates the vagaries and uncertainties of international conduct in adjacency to the mysteries and possible dangers of transformative technologies. Physicists have understood and exploited the interior workings of atoms enough to construct colossal nuclear weapons, and to prompt the mechanics of sub-atomic energy to generate artificial intelligence. But we do not fully understand the potential for adverse outcomes from new technologies. We already fear we no longer understand our world. The vital need is that countries agree to establish rules and controls to insulate humanity against the grave potential for new disruptions.

Yuval Noah Harari agrees with Klein that our ability to understand AI is “poor,” citing dangers inherent in artificial intelligence that teaches itself, thereby acquiring autonomous agency, capable of doing things we can’t foresee. But protective international governance of the application of artificial intelligence is needed just when international cooperation is breaking down. While US and Chinese preeminence argues for mutual accommodation in the interest of a more ordered world, America’s obsessive determination to stay “number one” encourages US tech giants to resist controls on use, as they rush to show support for Trump on the cusp of his second term.

Harari wonders how humans are intelligent enough to decipher the building blocks of life, and harness their force, while also doing extremely stupid and destructive things. A century ago, German physicist Werner Heisenberg, a pioneer in the theory of quantum mechanics, warned us the subatomic world “was unlike anything they had ever known…something that defied all expectation…a dark nucleus at the heart of things.”

The human factor seems almost as impenetrably mysterious. Just as human ingenuity interprets enough of the dynamic potential of quantum mechanics to advance transformative technological processes, without grasping all consequences, so transactional diplomacy and international pressures amplify dangers from human competition and avarice, without understanding their essentially corrosive outcomes.

Trump’s second presidency will not be normal, and we shouldn’t comfort ourselves by normalizing it in our minds. We face four years of damage mitigation and control. They will be strenuous but if the world and US institutions can avoid the worst, a time of reconstruction of predictability could follow. Trump’s go-it-alone pressures on conduct abroad may in some circumstances break destructive logjams, including in the Middle East.

Jonathan Freedland, in his year-end column for The Guardian, responds to a reader’s question: “How do we live in this terrible world?” “Perhaps by accepting that it’s the only one we have,” writes Freedland, “and that it’s not always so terrible – that sometimes, even quite often, it can be rather beautiful.”

Indeed. But our understanding of the world in which we live needs a re-set. Its inequities are widening. We can’t assume that the arc of human progress bends toward justice in a world where the definition of human progress has never been more bifurcated between power and people.

Canadians can, with like-minded state partners, work to build a reformed multilateral system to reestablish terms and norms of conduct between states, and to improve cooperative tools to manage climate change, nuclear weapons, and advanced technologies for the benefit and protection of us all.

But this overriding collective task needs leaders of stature concerned with the world of tomorrow, not only with the national interests today.

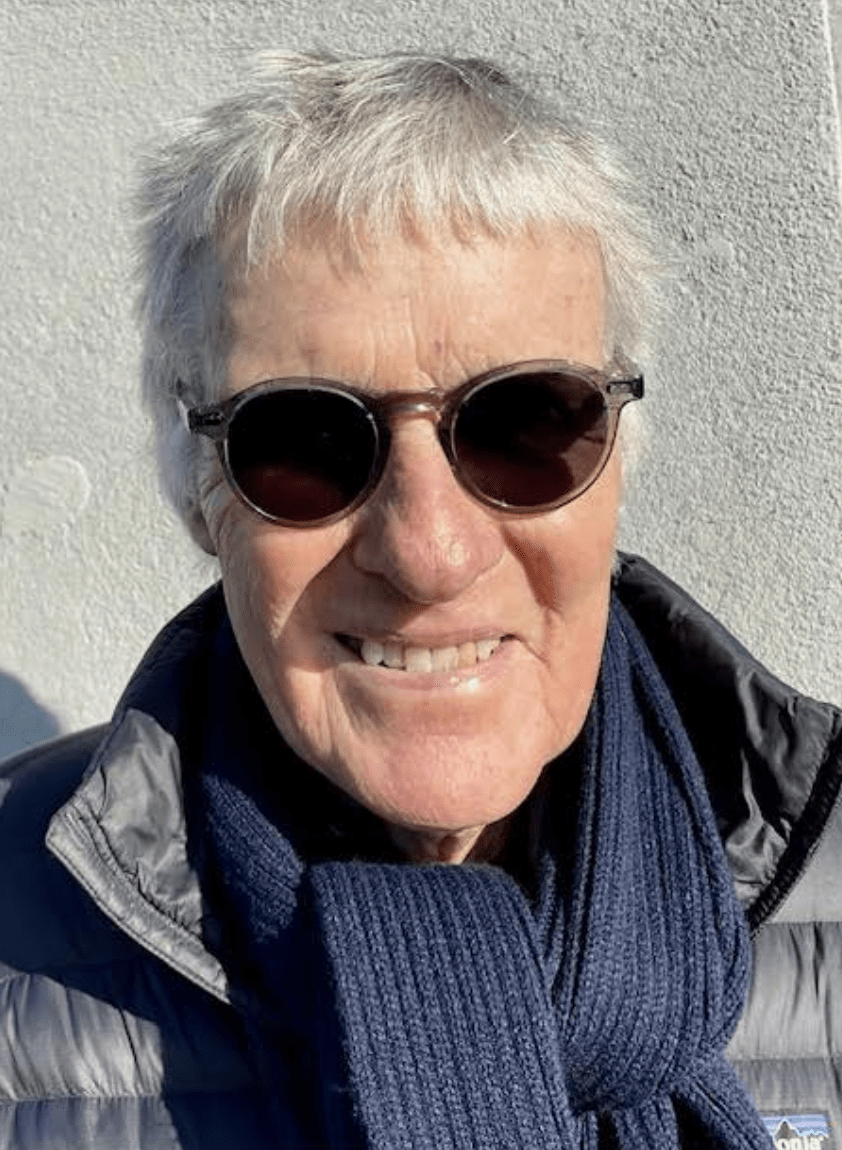

Policy Contributing Writer Jeremy Kinsman was Canada’s ambassador to Russia, high commissioner to the UK, ambassador to Italy and ambassador to the European Union. He is a Distinguished Fellow of the Canadian International Council.