Vladimir Putin’s War on the 1980s

Sky

By Charlie Angus

December 10, 2024

The recent launch of a Russian hypersonic ballistic missile marked a grim new phase in the Ukraine war. The Oreshnik missile struck the Pivdenmash military plant in Dnipro, Ukraine, which had once served as a state-owned Soviet missile factory, on November 21. It was launched, said Russian President Vladimir Putin, in retaliation for the decision by the United States and Britain to allow Ukraine to use their long-range missiles to hit targets in Russia.

“We believe that we have the right to use our weapons against military facilities of the countries that allow to use their weapons against our facilities,” Putin said in a pre-corded statement on Russian television.

Ukrainians are also introducing their own domestically made missiles. And in a dangerous tit-for-tat escalation, the Russians have ramped-up exercises for a new generation of nuclear-capable cruise missiles. Lest you think this is just about Kyiv, Sergei Viktorovich, commander of Russia’s Strategic Missile Forces, ominously pointed out that Russia has the capacity to hit targets “throughout Europe”. On December 6, Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said the Oreshnik strike sent a message that Russia is ready to use “any means” to stave off defeat.

All of this has frightening echoes of the 1980s and the white-knuckle showdown between American cruise missiles and the Soviet SS-20s. This 80s-redux theme isn’t coincidental. Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine seems to be rooted in his obsession to restore the “greatness” of Russia. To achieve this goal, he is apparently determined to rewrite the history of the last decade of the Soviet Union.

As Western governments, we ignore the lessons of the 1980s at our collective peril.

Let’s examine the state of two key nuclear limitation treaties, then and now. The missile crisis of the 1980s began in January 1980, when President Jimmy Carter suspended the second phase of the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT II). Carter was the furthest thing from a nuclear hawk, but he felt he needed to send a strong message following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan at Christmas 1979.

Tearing up SALT II shocked the Soviets and the world. It was the fruit of years of careful negotiations to limit the manufacturing of strategic nuclear weapons. Carter’s move came as the US military had begun integrating the new cruise missile into its arsenal. The cruise missile was a game changer. It was incredibly versatile, light and easy to move. A single B-52 bomber could carry 20 cruise missiles. It had the capacity to fly over 1,000 kilometres hugging the terrain to avoid radar. A sudden launch of cruise missiles would easily overwhelm the slower and less technically sophisticated Soviets. This put the Soviets on a hair-trigger response footing. Without SALT II to hold the military powers in check, the tension prompted a series of existential close calls in the fall of 1983 that nearly brought the world to the very brink of nuclear annihilation.

Per the frequently quoted Hemingway line, the Soviet Union collapsed gradually – throughout the 1980s – then suddenly, over the final weeks of the decade.

Our current, historical context-challenged political amnesia may have obscured the fact that we barely survived the 1980s. What kept the world from being obliterated wasn’t strongman posturing but the mass movement of ordinary people who took to the streets. First, they came small groups, then in hundreds, then in the hundreds of thousands.

On June 1, 1982, the largest protest in American history was held as one million people converged on Central Park to demand action on nuclear disarmament. Unprecedented levels of civil disobedience and citizen engagement pushed back the forces of war. In Canada, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau espoused nuclear disarmament as a legacy element, but his 1983 decision to allow testing of the Cruise missile in Cold Lake, Alberta, brought thousands of ordinary Canadians into the streets. By 1986, more than 100,000 protesters filled the streets of Vancouver, closing the Burrard Street Bridge.

Ronald Reagan is credited with ending the Cold War, but it was really the ordinary people who were determined to stop the nuclear madness. Mikhail Gorbachev said as much when he praised the women protesters at Greenham Common for inspiring him to search for a way to end the nuclear nightmare.

And yet, here we are again. This new and dangerous missile race comes at a time when the superpowers are on the verge of ripping up another key nuclear treaty. In February 2026, the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START Treaty) must be renegotiated. Given the toxic nature of relations with the Putin regime, its future is very much in doubt. START I led to an 80% reduction in nuclear weapons and without a renegotiated New START, the gloves will come off.

Per the frequently quoted Hemingway line, the Soviet Union collapsed gradually – throughout the 1980s – then suddenly, over the final weeks of the decade, between the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, and Boxing Day, when the Soviet of Nationalities ratified the Belavezha Accords consigning the USSR to history. At the time, Vladimir Putin was working as a KGB agent in Dresden under cover as a translator. In 2005, he cast the dissolution of the 20th century’s surveillance-state superpower, in which he was a member of the covert power structure, as “The greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century.”

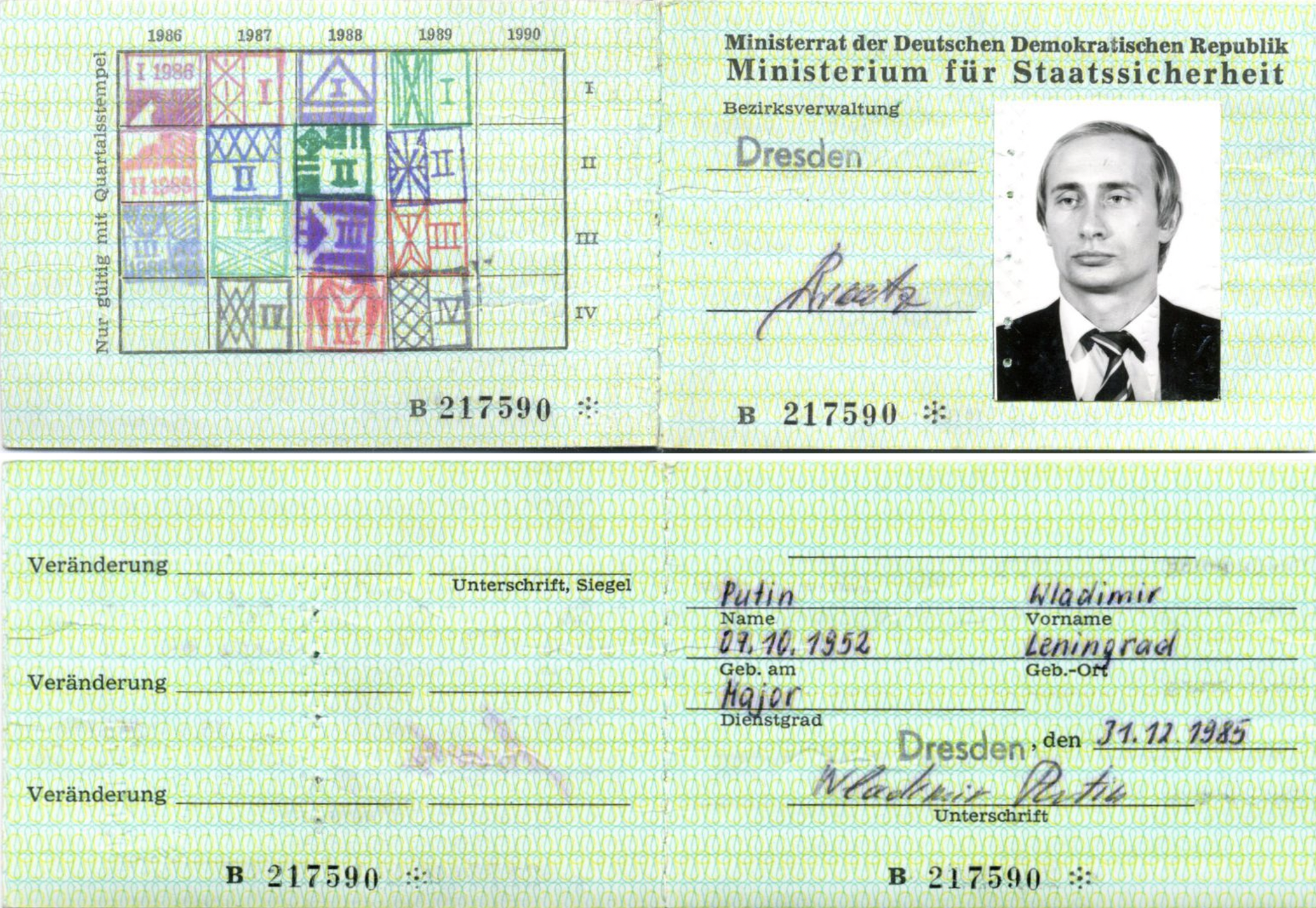

Vladimir Putin’s Stasi I.D. Card

Vladimir Putin’s Stasi I.D. Card

Putin’s unsettled score with the 1980s was evident in his response to Gorbachev’s death in August of 2022, most notably the Kremlin’s refusal to honour the man whose policies of glasnost and perestroika hastened the end of the USSR with a state funeral, and in his pointedly ambiguous description of Gorbachev as “a politician and statesman who had a huge impact on the course of world history.”

It was also evident in his recklessness over Chernobyl during the invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The 1986 explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in northern Ukraine was an unprecedented man-made environmental disaster. The nuclear radiation forced the evacuation of 335,000 people. Neighbouring Belarus had 23% of its territory contaminated by radiation. It is estimated that the region near the plant will be uninhabitable for 20,000 years. It remains the worst nuclear disaster in history. And on the very first day of the Russian invasion, Putin sent his forces into the exclusion zone surrounding the Chernobyl nuclear complex.

Russian forces then launched a firefight at the Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant, displaying an unprecedented level of military recklessness on Putin’s part and threatening a new nuclear nightmare that could have, once again, engulfed Europe in toxic contamination.

But the 1986 Chernobyl explosion wasn’t just an environmental disaster. Gorbachev said decades later that Chernobyl was a greater factor in the collapse of the Soviet Union than perestroika. The impacts of the disaster were so overwhelming that the Soviet state could not keep the facts hidden from the public or the world. At the time, Premier Gorbachev took to state TV in an unprecedented act of public openness. This was hailed as the beginning of the Soviet glasnost era. Gorbachev believed that such openness would allow the Soviet system to move forward.

Despite Gorbachev’s efforts to reform the system, the anger over the scale of the disaster and initial bungling provoked widespread suspicion of Soviet leadership and underscored the human cost of unaccountable autocracy. Not only did Chernobyl play a major role in bringing the Soviet Union to an end, it led to an irreconcilable breach between the peoples of Ukraine and Russia.

Author Serhii Plokhy states that Ukraine’s 1991 independence referendum, approved with an overwhelming 92%, would have been impossible to imagine without Chernobyl, and that the Soviet Union was one of the main victims of the nuclear catastrophe. At some level of dictator displacement, Putin’s recklessness regarding Ukrainian nuclear plants seems to be about punishing the people of Ukraine for the failure of the Soviets to contain the Chernobyl disaster.

The monolithic threat of the wall had defined the lives of millions for decades and yet it was brought down without a shot being fired, by the hands and hammers of euphoric civilians.

In reconsidering the 1980s, one question is obvious: how did we get from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the seeming hopelessness of this grinding war? Answering this may be most important lesson from that crucial decade because it is less about Putin, and more about the west.

The sudden collapse of the Iron Curtain in November 1989 was a moment of unprecedented people power and hope. The monolithic threat of the wall had defined the lives of millions for decades and yet it was brought down without a shot being fired, by the hands and hammers of euphoric civilians.

In the aftermath of the wall’s fall there was intense optimism over what could be accomplished if the two superpowers put aside their nuclear and military competition. It was called the peace dividend. Imagine how many global problems could be solved today if the superpowers put their energy into fighting problems like the climate crisis or global inequality. But that was not in the cards. Public investments were out. The neoliberal agenda was ascendant. And hubris was rampant. American political scientist Francis Fukuyama declared it the end of history: the good guys—the capitalists—had won.

The potential to create a democratic state in the Soviet Union was frittered away as neoliberal policies allowed former party apparatchiks to set up a fire sale of public assets for the benefit of rapacious privateers. Russians were subject to such extreme economic “shock therapy” that the life expectancy of ordinary citizens dropped by almost six years in the four years following the collapse of the Berlin Wall.

The looting of the post-Soviet state produced a degraded democracy, the Russian oligarchy and, eventually, the strongman politics of Vladimir Putin. The horrific violence unleashed by Putin’s illegal invasion of Ukraine has been called the “revenge of history.” It may more accurately be defined as the revenge of the 1980s.

In the period between the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the Ukrainian independence referendum, the Americans and the Russians began working on a series of military and diplomatic initiatives to rid the world of the nuclear threat. As the first START treaty was put in place in 1991, the Doomsday Clock launched in 1947 by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists (founded by Albert Einstein and J. Robert Oppenheimer two years erlier) was pushed back to 17 minutes to midnight.

As of January, 2024, the Doomsday Clock remains at 90 seconds to midnight, the closest we’ve ever come to nuclear apocalypse. But unlike in the 1980s, few seem to have noticed. And the ghosts of the 1980s are back in a very dangerous way.

Charlie Angus is the author of Dangerous Memory: Coming of Age in the Decade of Greed, a rethink of the ongoing impacts of the 1980s. House of Anansi Press.