Meanwhile, Back at the Economy…

By Douglas Porter

November 8, 2024

You know it’s been a week for the ages when the Fed cuts for only the second time in the past 4½ years and it’s almost an afterthought for markets. Yet, despite some very large swings before and after the U.S. election, the net move in many markets will look unremarkable, with not much trace of the Trump Trade 2.0, aside from stocks and crypto. For example, 10-year Treasury yields are currently sitting below levels prevailing at the end of last week, while the beleaguered yen and loonie are both a touch stronger. The obvious retort is that a Trump victory had been steadily priced in over the past six weeks or so, with only a few stutters along the way (including to start this week). And, of course, there was one standout move—stocks enjoyed a banner week, with the S&P 500 surging more than 4% to an all-time high, helping lift the MSCI World Index to a new record as well.

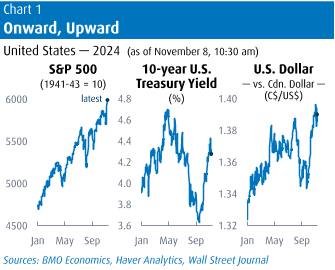

Buoyant equities were one-part enthusiastic response to the clear election result; one-part relief that the event was in the rear-view mirror; one-part welcoming of the Fed cut; and, one-part driven by a healthy underlying economic and earnings backdrop. True, the event risk is not completely diminished, as the fate of the House is still not fully settled, although the conventional wisdom is that the Republicans will hold their narrow advantage, thus completing a Red Wave (see this week’s Focus Feature for the full details). The main takeaway is that while there are many questions around the extent to which campaign rhetoric turns into policy reality, fiscal policy seems poised to be expansionary, the regulatory touch will be lighter, and business sentiment has strengthened—all putting some upside risk for growth, albeit with a dollop of mildly more inflation pressure. Supportive for equities and the dollar, but not so much for bonds (Chart 1).

We suggested last week that the next President would find a rude welcome on the fiscal front, but the economy is mostly rolling out the red welcome mat. GDP growth remains solid at nearly 3%; the unemployment rate is close to the “natural” rate at 4.1%; and inflation is considerably calmer, if not fully tamed. The Fed’s second rate cut, while a bit more grudging at 25 bps versus September’s 50 bp chop, was in recognition of the big improvement in the inflation picture over the past two years. The October CPI (due out Wednesday) is expected to see core rise 0.3% m/m, holding the annual increase steady at 3.3%, but that’s still down by 3 full percentage points from two years ago. Headline inflation may nudge up to 2.6% y/y, even with a mild 0.2% m/m move, but that will be down 5 full points from late 2022. As Chair Powell suggested many times at the press conference, policy simply does not need to be so restrictive as the current funds target (now 4.50%-to-4.75%) is running 2 ppts north of the core PCE deflator compared with a median spread of almost zero over the past 30 years. We have fine-tuned our Fed call, and now look for a slightly more gradual pace of rate cuts (125 bps by end 2025), with the terminal rate 50 bps higher than previously expected at 3.25%-to-3.50%.

The U.S. economic calendar was gracefully light this week, but the thin reports on offer were mostly positive. Auto sales had their second-best month of the past three years in October (16.2 million, versus a 12-month average of 15.7 mm). The services ISM had its best reading in more than two years at 56.0. A bump in initial jobless claims to 221,000 didn’t hide the fact that employment conditions have normalized after a hurricane-hit fall. Productivity growth was healthy at 2.2% in Q3, in line with the past year’s trend—a pace that is a bit above the long-run average, leaving it as one of the rare economies that has seen solid productivity gains in the wake of the pandemic. Firm productivity is a big reason why the U.S. economy has managed to lead G7 growth (and equity market performance), while faring no worse on the inflation front. While the economy played a starring role in the election campaign, often cast as the villain—with the lingering effects of inflation subbing in for Snidely Whiplash—the reality is that U.S. growth has been the envy of the world.

There’s likely not much global envy aimed at Canada’s economy these days, as it’s only managed GDP growth of little more than 1% in the past year. But there were some encouraging signs this week that the corner may have been turned. Similar to the U.S., auto sales came in strong last month, rising 8.8% y/y and now up more than 8% for the year. And the housing market is stirring, after napping through the first few BoC rate cuts. With the Bank’s recent 50 bp chop, that’s a world-leading (along with Sweden) 125 bps of rate relief in total, and buyers have hopped on board. Early results from the largest cities suggest that October home sales popped over 30% y/y, topping the 10-year average for the first time since early 2022 (when rates first began to rise). Employment managed another decent gain of 14,500 last month, keeping the jobless rate surprisingly steady at 6.5%.

It’s clear that the biggest economic concern in Canada has suddenly shifted from high interest rates and inflation to the uncertainty surrounding its U.S. trade relationship—akin to going from the frying pan into the fire. We sometimes noted as rates were rising that Canada was one of the most interest-rate-sensitive economies in the world. And, now, as U.S. protectionism looms, we note that Canada is one of the most U.S.-trade-sensitive economies in the world. Canada’s dependency is the same as it ever was, with merchandise exports to the U.S. running at 76.2% of the total in the latest month—exactly in line with the 30-year average. Canada stayed mostly under the radar during the U.S. election campaign—unlike Mexico, which even this week was threatened with 25% (or more) tariffs. But there have been no assurances that Canada will be spared broad tariffs, if they do come to pass.

Still, we are not ready to adjust our Canadian forecasts. First, we need to see the exact contours of what we’re facing on the trade front, as well as how the exchange rate responds. After all, a 10% U.S. tariff increase could be mostly negated by a similar response in the U.S. dollar (albeit with lots of side effects). But, more importantly, we would circle back to the simple reality that the single biggest driver for Canadian exports is the underlying health of the U.S. economy itself. In the first three years of Trump’s first term, before COVID erupted in early 2020, Canada’s economy managed to churn out average real GDP growth of 2.5% (while the U.S. was growing 2.8%), a sturdy pace even amid all the uncertainty swirling around the fate of NAFTA at that time. We will thus now focus on what policymakers actually do, not what candidates say.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.