The Next President’s Rude Welcome

By Douglas Porter

November 1, 2024

Heading into the home stretch of the U.S. election—what, already?—financial markets have displayed a flash of nerves after holding remarkably firm through most of the early fall. Major equity averages blithely marched higher through the most seasonally challenging period, but have since turned cautious, dipping about 3% from the record highs of two weeks ago before stabilizing on Friday. Even tech stocks, which have carved out their own path, faltered right after the Nasdaq hit a new high earlier this week. But despite the step back, the bigger picture is that stocks have managed to grind out some modest gains since the end of August in the face of numerous geopolitical risks and the deep uncertainty of next week’s election.

Alas, the bond market has not shared the good fortune of equities in the past two months. After touching lows just ahead of the mid-September FOMC meeting, and the 50 bp Fed rate cut at that time, it’s been mostly one-way traffic north for yields. Two-year Treasuries have risen by 60 bps since that time, landing back above 4.15%, while 10s are up more than 70 bps to over 4.3%. And that’s even after yields took a very brief step back in the wake of the messy October jobs report—which revealed a mere 12,000 net payroll increase, and hefty downward revisions to earlier months. Average earnings were close to expectations (+4.0% y/y), while the unemployment rate held fast at 4.1% as anticipated, even with a big, hurricanes-related, 368,000 drop in household employment.

While heavily distorted, the underlying message from jobs seemed just soft enough to convince markets that the Fed will indeed proceed with a 25 bp rate cut at next Thursday’s FOMC. The path gets a little less clear after that, with the market expecting at least one pause at some point in the following four decision dates. We suspect the pause will be on the later side and are sticking with our call of four consecutive 25 bp trims, eventually taking the overnight rate to just below 4% by March, and to under 3% by early 2026 from just below 5% now. But the risk to the call is that the Fed will proceed a tad more cautiously, in part depending on the election outcome.

One of the reasons yields have been steadily marching higher in recent weeks is the ongoing resiliency of U.S. growth. Prior to the jobs report, the weight of evidence had been heavily sitting on the strong side of the scales—tilting that way almost from the moment the Fed opted for a supersized rate cut. Real GDP rolled to a still-solid 2.8% annualized pace in Q3, slightly above the average of the past four quarters (2.7%), and well north of potential growth (closer to 2%). The rock-solid growth has been broad-based, with the consumer at its heart. Overall personal income is up 5.6% y/y, more than 3 percentage points above current inflation (now just 2.1% on the PCE deflator), and consumer confidence bounced to its best level since January last month. Against that backdrop, it’s hardly surprising that Fed rate cut expectations have been reeled in and yields have pushed higher.

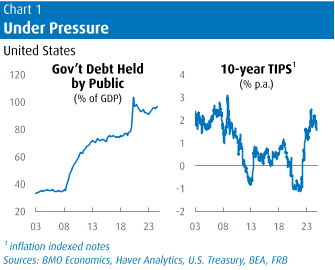

But a slightly less friendly interpretation of the list of factors behind the sustained backup in yields in the past seven weeks would include growing concerns about the fiscal backdrop. The budget deficit for the fiscal year that ended in September came in largely as expected at $1.83 trillion, or 6.4% of GDP over that same period. That boosted debt held by the public to 96.4% of GDP, which is up more than 20 ppts since 2016 (mostly, but not exclusively, reflecting the heavy fiscal costs of the pandemic). More staggeringly, the debt/GDP ratio is now up more than 60 ppts just since the pre-Great Recession days of 2007 (Chart 1).

As we have asserted previously, the combination of the return of positive real interest rates and less-favourable demographic factors could put pressure on the fiscal outlook for years to come. Even under reasonably positive economic and interest rate assumptions, the debt/GDP ratio is poised to continue marching higher in the second half of this decade, taking it well above 100% and even above the prior highs just following WWII. The reality is that neither presidential candidate has offered any serious path to reining in the budget deficit—quite the opposite for the most part.

Non-partisan analysis points to wider budget gaps regardless of who wins under current proposals. But it’s safe to say that financial markets are of the view that Trump’s slate of policies are more expansionary and will boost the deficit further. Added to a variety of proposed tariffs, which could nudge inflation higher, this is clearly a factor behind the increasing anxiety in Treasury markets, especially with the polls essentially back to 50-50 again (well, technically 48-48). Whoever occupies the White House next will soon face the tough debt and deficit realities, and a possibly twitchy bond market that won’t take kindly to lax fiscal policies. Of course, the market will also be hanging on to the ultra-tight races for the House and Senate—a split Congress, while setting up a showdown on the debt ceiling, would likely be mildly reassuring for Treasuries, since it would block the most ambitious policies for whoever wins.

Arguably, it was the U.K. that first alerted the world to the possibility that the bond vigilantes could make a comeback, courtesy of Liz Truss and the ill-fated mini-budget two years ago. In a twist of fate, the U.K. budget again briefly seized the main stage this week, just days ahead of the U.S. election, and made a mark on markets (albeit less ferocious than in 2022). Gilt yields, which had largely been shadowing their U.S. counterparts, took a big step higher, with 10s up more than 20 bps to above 4.4%—that’s not far from the peaks reached two years ago, albeit with much less drama. While probably a bigger deal from a political standpoint than an economic lens, the first budget from Labour delivered a heavy dollop of business taxes without meaningfully improving the fiscal outlook—hence the sour market reaction. The lesson for policymakers everywhere is that markets are again highly attuned to fiscal matters, and in the wake of the recent inflation episode, will not be in a forgiving mood for any missteps.

The Canadian dollar is coming under sustained downward pressure, but this move is mostly related to monetary, not fiscal, policy. The Bank of Canada has been the most aggressive rate cutter in the G10, with 125 bps under its belt and apparently more on the way. Even as the currency has drooped below 72 cents (or just above $1.39/US$), BoC Governor Macklem continues to aver that Canada/U.S. rate spreads are nowhere close to their limits, pouring yet more cold water on the loonie. We would quibble with that view—short-term spreads of around -100 bps are at levels last seen in 1997, and aside from the episode in the mid-1990s they have never been as negative in the past 50 years. Clearly unperturbed by the sagging loonie, the Governor suggested at his Senate testimony that the BoC may well cut by 50 bps again.

This week’s GDP report turned up the odds of a meatier move, as it pointed to just 1.0% growth in Q3, a bit weaker than the average 1.3% pace over the past year and nearly 2 ppts south of U.S. growth trends. It is this yawning growth gap, and the fact that inflation is basically back at target, that has the Bank seemingly unconcerned about the loonie’s fate. The Bank is apparently of the view that there is precious little pass-through risk to inflation from even a heavy depreciation. Given the BoC’s loonie-faire stance, and the clear risk to the currency from U.S. election results, the Canadian dollar looks like it will remain under serious pressure for some months yet.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.