‘The Twelfth of February’: Women’s Rights as the Canary in the Coal Mine of Democracy

By Rhonda Gossen

McGill-Queen’s University Press/September 2024

Reviewed by Margaret Huber

Reading Rhonda Gossen’s thought-provoking book The Twelfth of February: Canadian Aid for Gender Equality During the Rise of Violent Extremism in Pakistan is, for me, a journey through time and space. In 1976, I first visited Pakistan as a young officer travelling overland from Islamabad through the Khyber Pass to Kabul. I was there to consult on Asian Development Bank (ADB) irrigation, power and road development projects in Afghanistan and Pakistan (while serving at the Canadian Embassy in the Philippines, as commercial liaison with the ADB headquarters in Manila). It was eye-opening.

Pakistan and Afghanistan are lands shaped by memories of empires…including those of Alexander the Great, the Mughals and the British heirs of the East India Company. Years after that first trip, I was privileged to serve as Canadian High Commissioner in Islamabad from 2003 to 2005.

As such, I did not overlap in the field with Gossen, a fellow Canadian diplomat who has worked directly on Pakistan programs in various capacities, for UNHCR, UNICEF, World Bank, and at the Canadian High Commission in Pakistan 2010-2014. However, both the issues and her own experiences, expertly described, are disturbingly familiar.

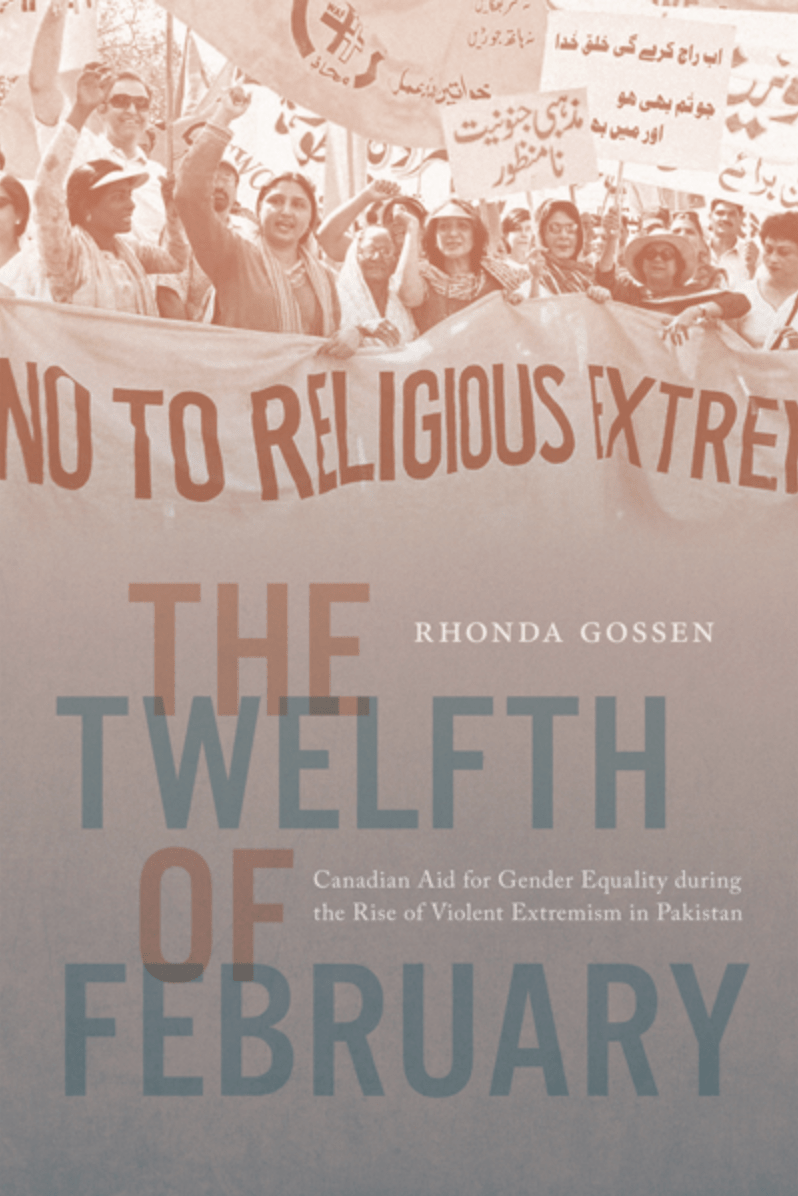

This book is her first, commanding respect for her comprehensive analysis of events leading up to and flowing from the events of February 12, 1983, the landmark day in the evolution of women’s rights in Pakistan when hundreds of women marched on the Lahore High Court to protest dictator Gen. Mohammad Zia-ul-Haq’s repressive and discriminatory Law of Evidence which, among other features, equated the testimony of two women to that of one man.

Those February 12th 1983 demonstrations for gender equality by courageous women leaders such as Asma Jahangir, internationally celebrated human rights lawyer and democracy activist, eventually entrenched the date as National Women’s Day in Pakistan. Gossen’s examination of the consequences and impact on Canadian development aid for gender equality are clearly based both on her long experience as a practitioner and on deep scholarly research.

Most interesting to me in this book is the conclusion Gossen draws: how a gender lens on security, development and diplomacy can help combat forces threatening human rights and democracy.

Nineteen eighty-three was a critical year for Pakistan, for Canada and also for the Aga Khan Development Network, with which Canada was to work closely to advance development initiatives in Pakistan (including the linking of health care programs at McMaster University in Hamilton and the Aga Khan University in Karachi, which was chartered in 1983).

I met with H.H. the Aga Khan on a number of occasions during my time in Pakistan, as well as in Europe and in Canada. Like others, I was impressed by his leadership, his love of architecture and great design, his entrepreneurship and most of all, by his commitment to the uplifting power of education (he often quoted his legendary grandfather: “Personally, if I had both a boy and a girl and I could afford to educate only one, I would have no hesitation ..the girl”).

In her book, Gossen considers the turning point of the 1983 events against the backdrop of regional geopolitical conflicts, the Afghan Wars and the Islamization of Pakistan by authoritarian leader, Gen. Zia (who also fast-tracked Pakistan’s nuclear program, attaining the capability to detonate a nuclear weapon in 1984).

Later, while addressing the challenges of Pakistan myself, having arrived in Islamabad only two years after the tectonic shifts of 9/11, I was deeply impressed in by fearless development-specialist colleagues … by the innovative skills, calculated risk-taking abilities and dedication that they continually demonstrated. Our then-development counsellor, Rolando Bahamondes, with whom I worked closely, led the way for us to leverage financial assistance for key initiatives. He and the development team forged strategic partnerships with multilateral and bilateral donors with deeper pockets, and worked with local partners throughout the country on community-based delivery approaches. Canada has been blessed with such talent.

Gossen’s book is a landmark study. The next edition will doubtless see corrected the few factual errors that have crept in; for example, the book inadvertently refers to ‘the late’ John Manley. Actually, Manley is still very much alive and active, serving as chair of Jefferies Canada and continuing to speak out on international issues of concern.

Most interesting to me in this book is the conclusion Gossen draws: how a gender lens on security, development and diplomacy can help combat forces threatening human rights and democracy. The degree to which this is so, and what more can be done now, deserve closer examination and study (universities and think tanks in Canada and elsewhere, please take note). As we are now in a period of growing polarization and extremism, widely endangering democracies at home and abroad, Gossen’s conclusion warrants urgent attention. Reading her timely book is a great start.

Margaret Huber served as Canada’s High Commissioner to Pakistan from 2003-2005.