War and Politics in the Digital Age

The Moscow Times

The Moscow Times

By Sam Howard

September 20, 2024

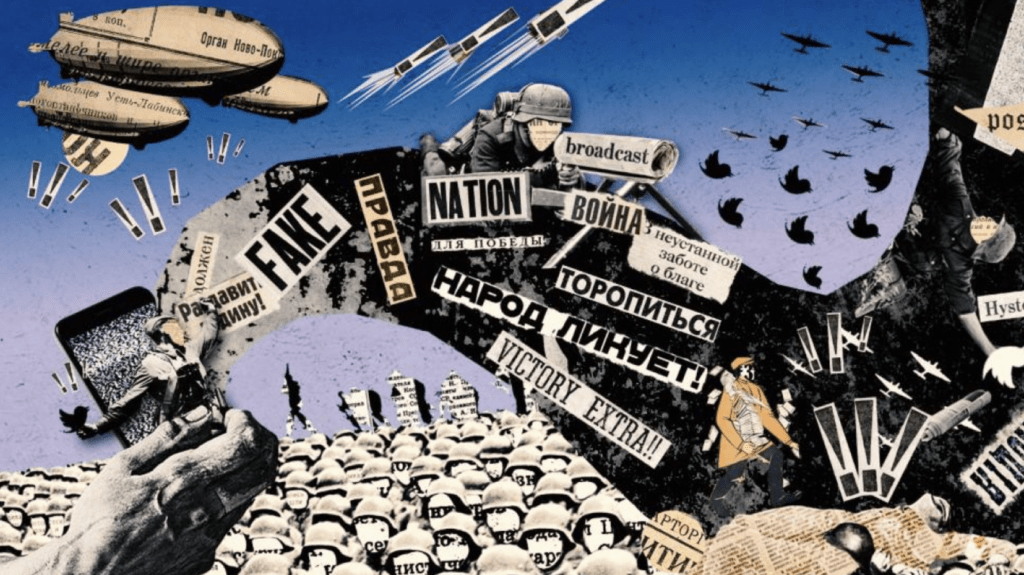

It would take little more than a quick scroll on social media for the average user to encounter images or reports related either to the Ukraine War or the upcoming US elections. This reality reflects perhaps the most striking realization metabolized over the past few years: that history is now firmly in the grips of a fourth industrial revolution. In the two major arenas of human events — war and politics — the metamorphic effects of digital technologies have become undeniable.

The global internet has expanded and deepened the connections among people and places in ways unthinkable just half a lifetime ago, allowing for the collapse of time and space in the worldwide exchange of information. One key dimension impacted by the digital era of geopolitics is war, which has been transformed by digital information and communication technologies (ICTs) enabled by the internet. The internet and the networked environment it has created have not only revolutionized the conduct of military operations, but have also made the perception and communication of modern warfare arguably as important as combat itself – if not more so.

The same might be said of other forms of political conflict, especially elections, if we accept Foucault’s notion of ‘politics as war by other means’ (an inversion of the famous Clausewitzian phrase). The election campaign may not be a military melée, but it is certainly a showdown of ideologies – or, perhaps more accurately these days, a clash of personalities and worldviews. Indeed, the internet has transformed the electoral battlefield, providing new media and larger audiences for the weaponization of lies and the manipulation of public opinion.

The ongoing war in Ukraine presents a case in point of how armed conflict increasingly plays out on the digital front. As shells flew across the frontline and Russian armoured vehicles rumbled into Kherson, Kharkiv, and even Kyiv, live videos and images documenting the terrors of war and the bravery of Ukraine’s defenders similarly traversed cyberspace.

Finding their way onto the screens of locals and internationals alike, such digitally disseminated images inspired widespread international support and contributed to domestic mobilization for the war effort. That said, the remarkable quantity of content shared from the frontlines has arguably done as much to obscure reality as to represent it, as reliable information is often but a drop in the wider cyber-sea.

On the frontlines, the Ukrainian military also uses the internet for its communications internally and with civilian populations, and for the conduct of its drone warfare. However, Ukraine’s reliance on a stable network connection has also empowered private actors, such as Elon Musk and his company Starlink, to mediate the war’s conduct in critical ways, for example by determining where and to whom internet access is granted.

In response to Ukraine’s effective instrumentalization of cyberspace, Russia has taken steps to consolidate its own control over digital information flows, mainly by disrupting Ukraine’s connectivity and spreading disinformation online. In the region of Kherson, for example, the Russian occupation first shut off internet access to locals, before deliberately rerouting the regions’ internet traffic through Crimea-based service providers tied to the Russian government. Similar phenomena had previously been documented in Crimea after its capture by Russia in 2014, telegraphing how Russia aimed to annex Ukraine’s cyberspace alongside its physical territory.

The internet has transformed the electoral battlefield, providing new media and larger audiences for the weaponization of lies and the manipulation of public opinion.

Those connected to Russian networks became subject to Russia’s oppressive internet governance regime characterized by censorship and surveillance. Indeed, as part of a burgeoning anti-Western movement in global cyber governance, revisionist powers like China and Russia have increasingly challenged the principles of free information flow and expression online. Instead, they assert their digital sovereignty as justification for restrictive cyber policies. Russia’s ‘sovereign internet’ project, for example, aims to isolate Russia’s internet from the rest of the world, establishing a ‘splinternet’ that ensures state control over speech and conduct online.

By monitoring and suppressing information shared over its internet network, Russia aims to insulate its population from what it considers to be outside threats to the Putin regime’s power. In the Western world, similar behaviours are – at least on paper – deterred by liberal-democratic values. Nevertheless, there are few barriers preventing politicians in the West from leveraging the internet in different ways, as a means to manipulate public opinion via propaganda.

Former president Donald Trump, for example, has repeatedly relied on social media as a vehicle for the dissemination and amplification of virulent misinformation, most recently going viral for popularizing the outlandish claim that illegal immigrants were devouring house pets in Springfield, Ohio. Though a quick google search could prove this bizarre notion false, the overabundance of information shared online – real and manufactured – allows spuriously labelled ‘alternative facts’ to take hold. In this case, it was out-of-context police bodycam video Trump supporters turned to as alleged ‘proof’ of this racist internet rumor.

Foreign actors such as Russia also seize the opportunity of election campaigns to manipulate online information available to Western electorates through clandestine online influence campaigns. As Canada faces its looming election, a recent exposé by European and American officials revealed how a website posing as a legitimate news source was instead promulgating Russian propaganda intended to discredit Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. This comes as US authorities allege that individuals linked to Russia’s state-run media organization, Russia Today, funneled nearly $10 million to right-wing political commentators, who in turn published content echoing Russian propaganda narratives to their substantial online audiences.

As the internet continues to rewrite the script of contemporary political conflict, it is important to question whom its authors are. Outside the Western sphere of influence, it appears that authoritarian governments are taking on this role, enacting legislation empowering them to govern their respective internet networks, and, by definition, information environments, as they see fit. Within the West, however, it is an increasingly powerful private sector that seems to be writing the rules.

Ukraine’s resilience, for example, can to a significant extent be attributed to support from major international tech and social media companies, which helped secure Ukraine’s networks and regulate Russian content online. During elections, it is similar private entities who control the online platforms predominantly used to share information, in turn influencing electoral outcomes.

Though such companies sometimes display a willingness to cooperate with governmental objectives, as in the case of private sector commitment to Canada’s Declaration on Electoral Integrity Online, other platforms like the Musk-run X (formerly Twitter) exhibit more obstructionist, politicized intentions. And although the recent arrest of Telegram’s CEO suggests that Western governments might increasingly attempt to hold private actors responsible for activity on their platforms, debate over online freedoms will continue to undermine any meaningful attempts at internet regulation.

Though the Ukrainian case demonstrates the critical importance of a stable and free internet for national and international security, the experiences of Western elections underscore how information shared over the internet can be a source of vulnerability and a threat to democracy. Meanwhile, the private actors engaged in cyberspace are garnering an almost governmental quality, influencing where, how, and to whom information is shared online. If one thing is clear from these developments it is this: in the elections of the internet era, as in modern warfare, all is not quiet on the digital front.

Sam Howard is an MSc student at the London School of Economics and Political Science in the Global Politics program. His dissertation deals with the impacts of network disruptions on information flow during the Ukraine war. He earned his BA in political science at McGill University.