Rebalancing Canada’s Housing Market

By Tony Stillo and Michael Davenport

August 19, 2024

Research highlights:

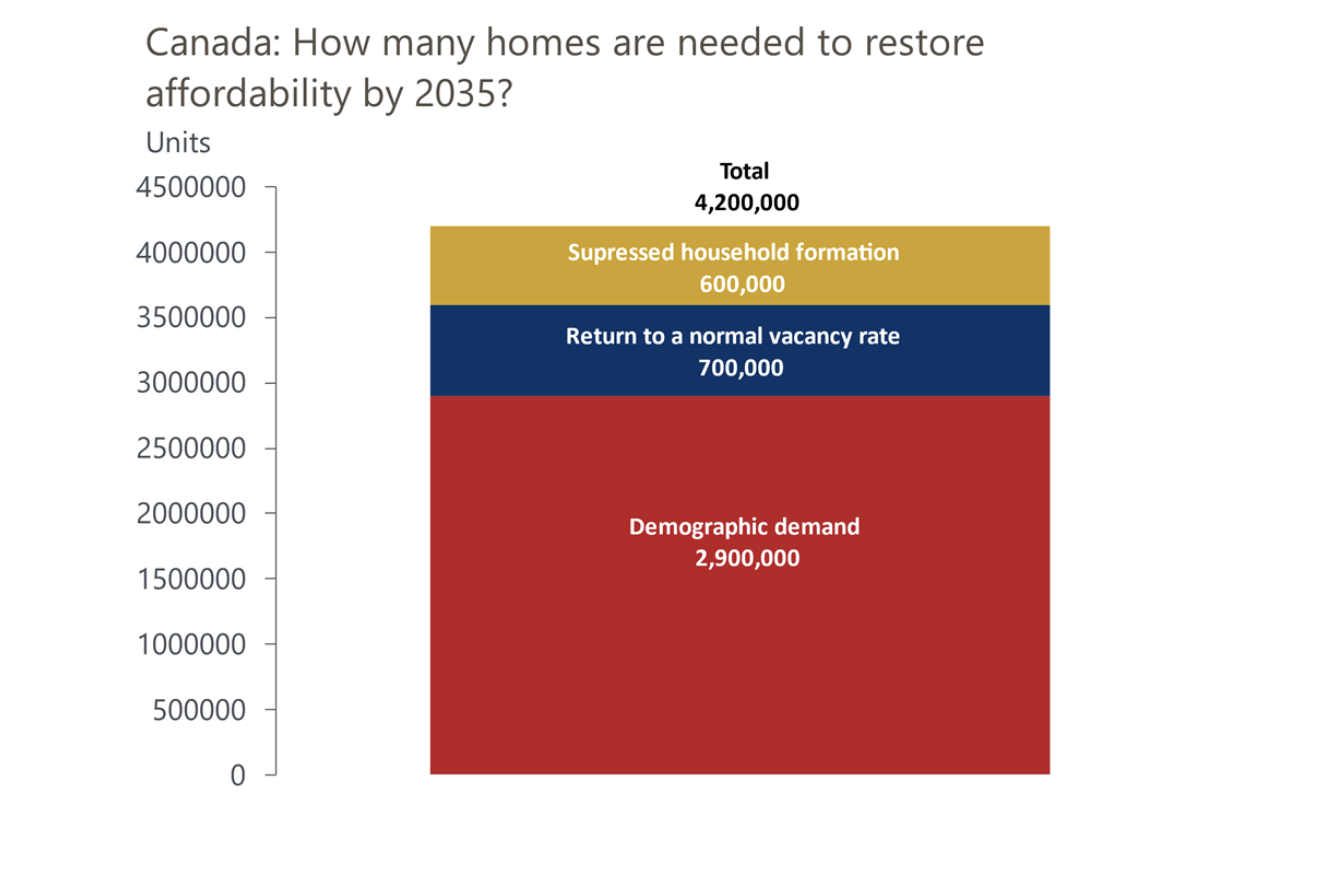

- We believe that building enough homes to restore housing affordability across Canada will likely take another decade. To balance the housing market, we estimate 4.2mn new dwellings need to be built between 2024-2035, including 2.9mn to satisfy growth in households and 1.3mn to make up for past supply shortfalls, ensure a normal vacancy rate, and to remedy suppressed household formation due to unaffordability.

- While it will take a long time to construct the new dwellings Canada needs, we expect growth in the housing supply will be stronger than housing demand in the coming decade. This means house prices will rise more slowly than median household incomes. Housing affordability should progressively improve, with home ownership back within reach for typical households by 2035.

- Our analysis finds that the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s (CMHC) aspirational target to build 3.5mn houses by 2030, on top of those required for household formation, is not feasible and significantly overstates the actual number of new dwellings needed to restore affordability. Construction capacity constraints, worker shortages, and other challenges make the requisite near-tripling of the current pace of new home building through 2030 almost impossible.

- Moreover, we have key concerns regarding such a massive potential addition to Canada’s housing supply. It would result in about 1 in 5 dwellings being unoccupied, raising the risk of an over-supplied housing market and a prolonged house price slump, especially as aging baby boomers begin selling or bestowing their homes in the mid-to-late 2030s. Devoting too many scarce resources to residential construction would likely crowd out business non-residential capital investment, hurting Canada’s longer-term economic potential and productivity growth.

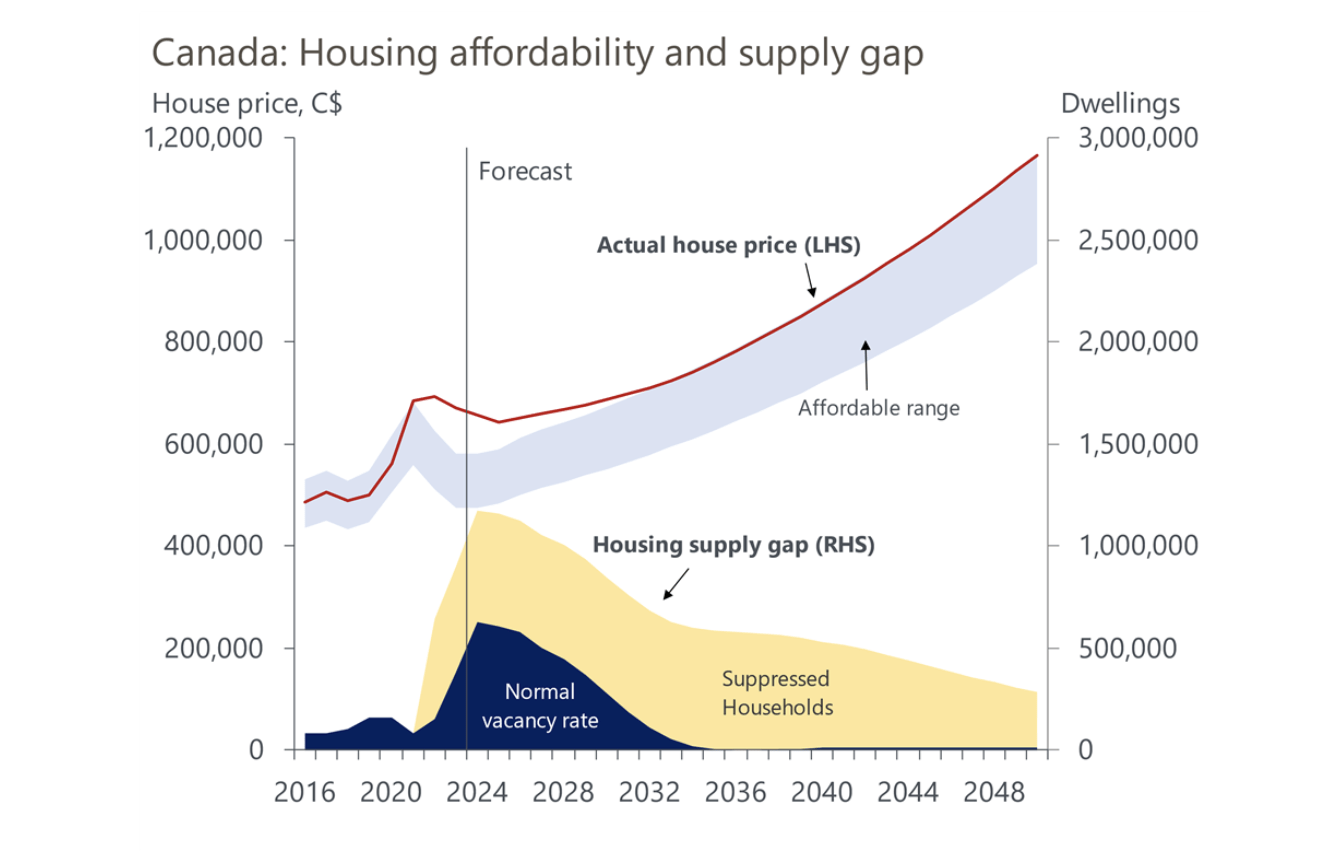

Canada’s housing market has been chronically undersupplied in recent years (Chart 1), begging the critical question: How many homes need to be built to return the market to balance and restore affordability? Ultimately, the country needs to build enough houses to keep up with growing demographic demand, account for demolitions and net conversions, and make up for the existing supply shortage by ensuring a “normal” vacancy rate (one consistent with a balanced and affordable housing market), but also add more dwellings to remedy suppressed household formation due to unaffordable housing.

Chart 1: It will take another decade to close the housing supply gap and restore affordability

Source: Oxford Economics/Haver Analytics

Source: Oxford Economics/Haver Analytics

Canada’s housing stock grew from 12.5mn in 2001 to 16.9mn in 2024

Before assessing how many houses need to be built, it’s important to have a tractable estimate of the existing housing stock. To estimate Canada’s housing stock, we start with the 2001 census data on the total number of private dwellings and grow it forward using StatCan and CMHC data on conversions, deconversions, demolitions, and completions. The current year’s housing stock is equal to the previous year’s stock, plus the new homes completed and the net number of dwellings converted from non-residential to residential purposes, less the number of demolished units. Using this approach, we estimate the total number of private residential dwellings grew from 12.5mn in 2001 to 16.9mn units in 2023.

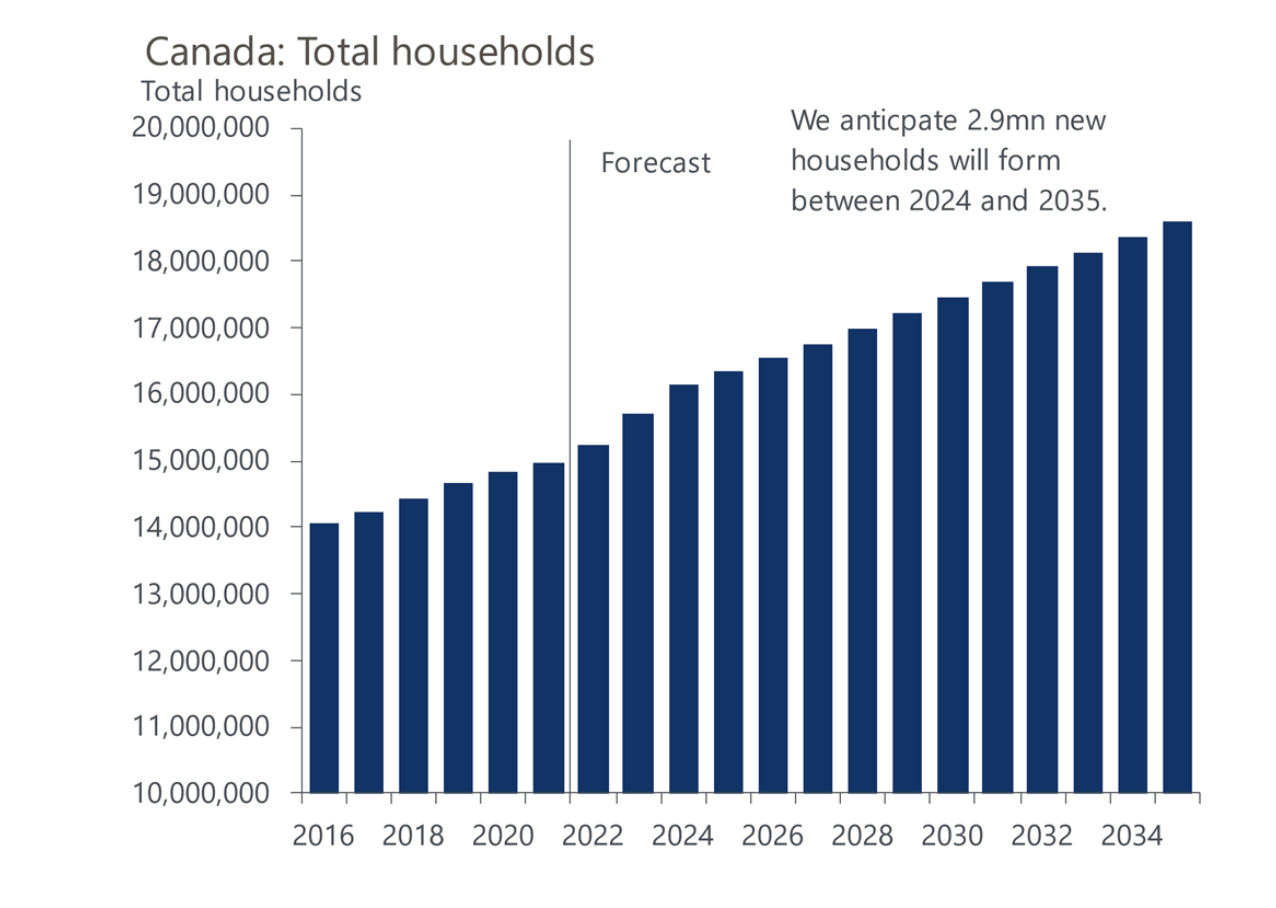

Household formation will remain strong despite slower population growth

First and foremost, Canada needs to build enough houses to keep up with the underlying demographic demand for shelter. There were just under 15mn households in Canada in 2021, according to the census, and we estimate the recent surge in population growth increased that to around 15.7mn households in 2023. Even with our projection for a sharp slowdown in population growth due to the Federal government’s target to reduce the share of temporary residents to 5% of the population by the end of 2027, household formation will likely remain high by historical standards through the remainder of this decade.

Assuming headship rates hold steady at 2021 levels, we project another 1.8mn new households will form between 2024-2030, bringing the total number of households in Canada to just under 17.5mn by the end of this decade. Another 0.9mn new households will likely form by 2035, bringing the total to 18.6mn (Chart 2).

Chart 2: We project 2.9mn new households between 2024-2035

Source: Oxford Economics/Haver Analytics

Source: Oxford Economics/Haver Analytics

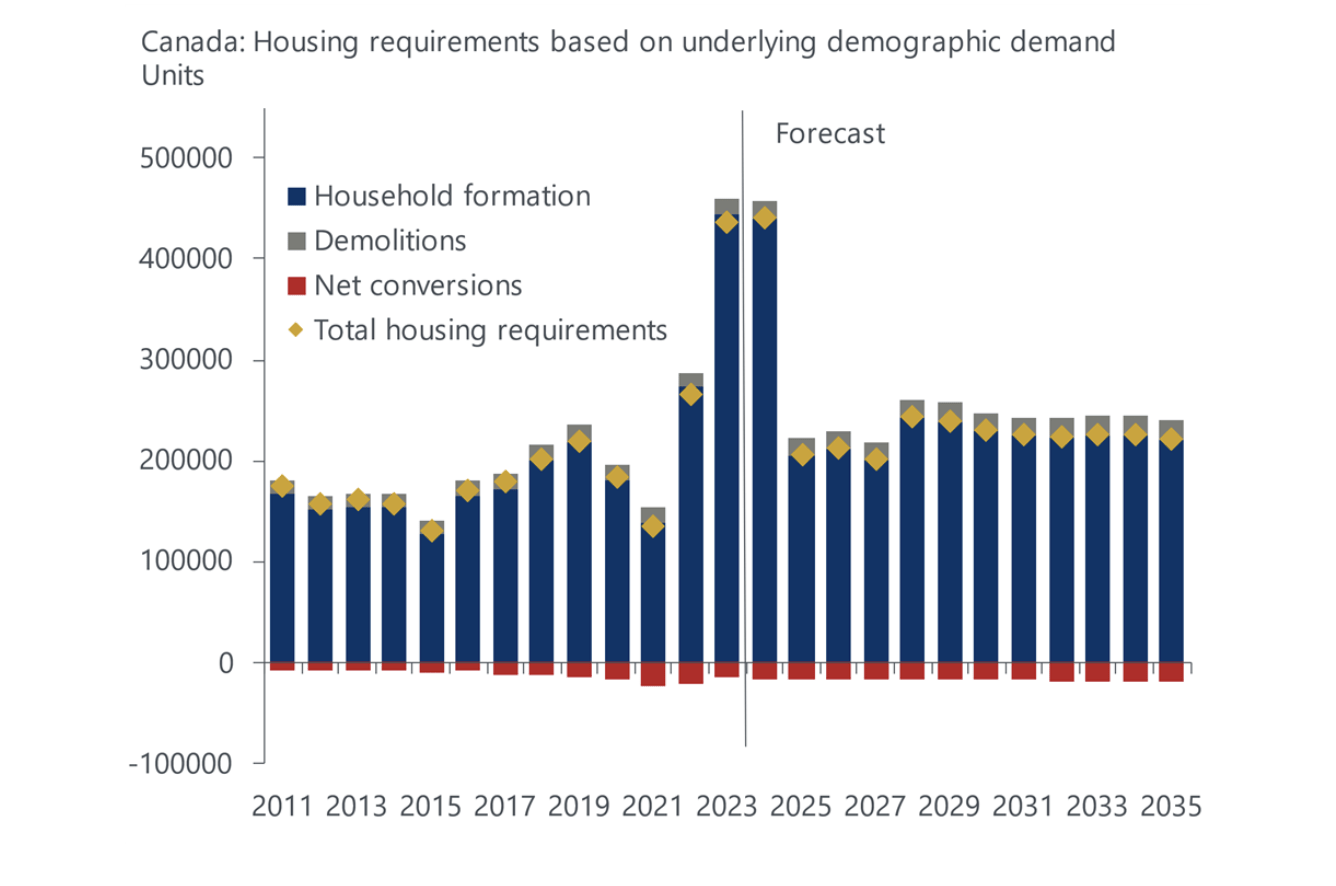

After accounting for net conversions and demolitions, which make up a relatively small share of the total housing stock each year, we estimate Canada’s additional housing requirements will total 2.9mn between 2024-2035. This means an average of 240,000 new housing units will be needed per year between 2024-2035 just to keep up with growth in the population and to replace net losses to the existing stock. This is well within the building capacity of the residential construction sector. For context, housing starts averaged about 260,000 units between 2021-2023.

But building enough houses to keep up with demographic demand and replace demolitions and net conversions won’t be enough to return the national housing market to balance and restore affordability. The housing stock has failed to keep up with the rapid growth in household formation in recent years, exacerbating the country’s prevailing undersupply of housing. Moreover, near-record housing unaffordability has caused many younger Canadians to delay forming households, leading to a rise in suppressed household formation that, while challenging to quantify, also needs to be accounted for.

Chart 3: Underlying demographic demand will keep housing demand strong

Source: Oxford Economics/Haver Analytics

Source: Oxford Economics/Haver Analytics

Housing requirements alongside an affordability target

For the housing market to return to balance, the national vacancy rate needs to be aligned with a long-term equilibrium level that is consistent with affordable housing prices. The vacancy rate not only captures uninhabited dwellings, but also homes that are unoccupied due to regular turnover in the resale market, those that are temporarily empty for renovations, short-term rentals (STRs), and second homes like vacation homes, cottages or cabins.

Using our estimate of the housing stock and official StatCan census data for the number of households, we calculate the national vacancy rate as the housing stock less the number of households, divided by the total housing stock. Canada’s national vacancy rate hovered around 8% on average during the two decades before the 2020 pandemic. However, because growth in the housing supply failed to keep up with the rapid pace of household formation in recent years, we estimate the vacancy rate dropped to 6.9% in 2023 and will likely fall further to 5.7% in 2024.

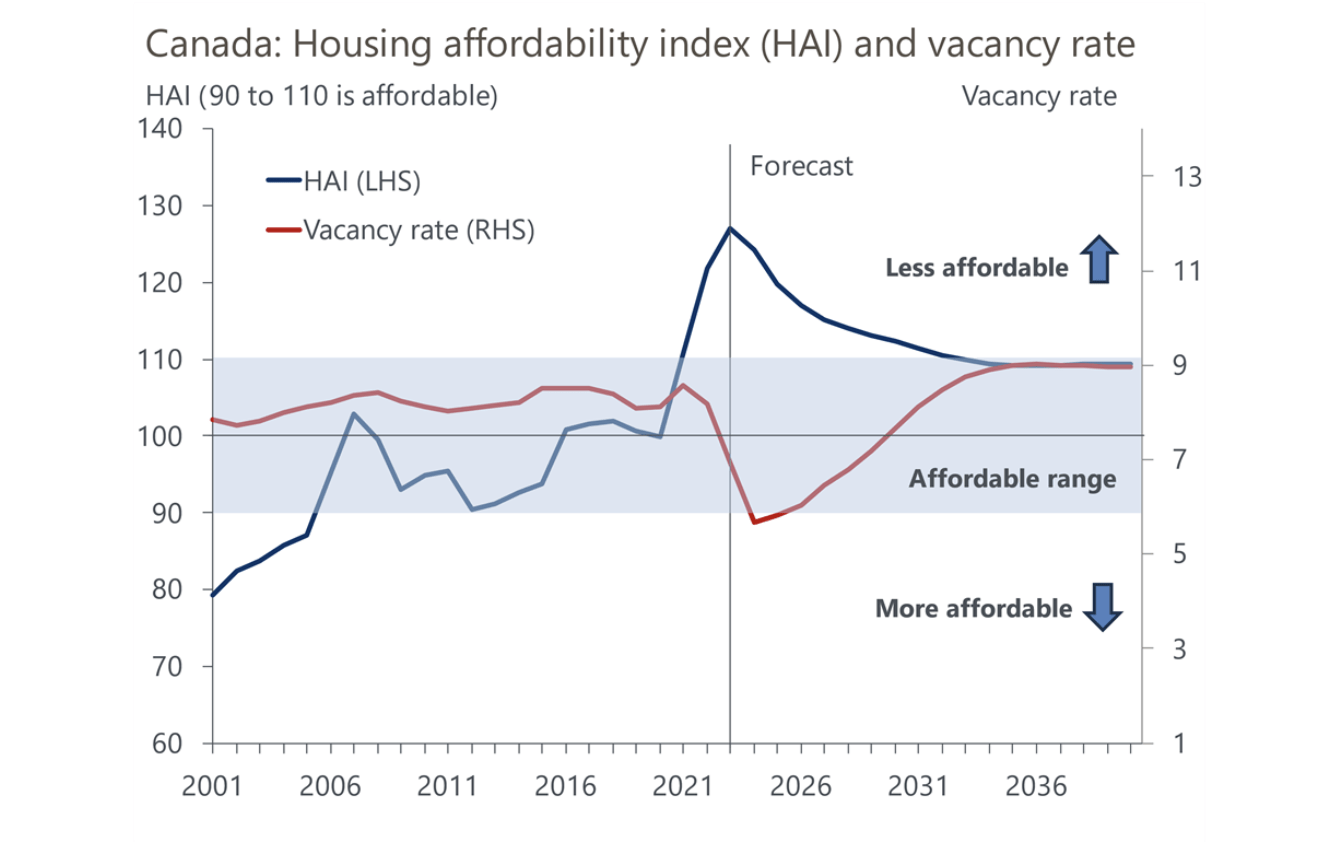

To help determine the long-term equilibrium vacancy rate, we use our Housing Affordability Index (HAI) to identify the last time housing was affordable for a sustained period at the national level. Between 2015-2018, our HAI averaged 100, meaning the average-priced house in Canada was affordable for median-income households. During this same period, the national housing vacancy rate averaged 8.5% (Chart 4).

We also consider that a small portion of dwellings are not available as primary residences and that these need to be accounted for when assessing the long-term equilibrium housing stock. This includes dwellings that are used as STRs and under-used housing as indicated by the number of homes subject to the federal government’s Under Used Housing Tax.

These types of homes grew from just under 0.5% of Canada’s housing stock in 2017 to around 0.6% in 2024. In the interest of taking a more conservative estimate of the impact of STRs and underused housing, we assume this share will rise to just under 1% of the total housing stock by 2030. This adds a wedge of 0.5% onto the 8.5% equilibrium vacancy rate that was consistent with affordable housing back in the 2015-2018 period, meaning our analysis targets a 9% long-term equilibrium vacancy rate for 2030 and onward. Accordingly, even if Canada builds the 2.9mn houses required to keep up with household formation between 2024-2035, an additional 700,000 dwellings are also needed to return the national vacancy rate to the long-term equilibrium level of 9%.

Chart 4: Housing affordability and a balanced market won’t be achieved until the mid-2030s

Source: Oxford Economics/Haver Analytics

Source: Oxford Economics/Haver Analytics

Suppressed household formation also needs to be considered

In addition, a significant number of homes need to be built to make up for suppressed household formation due to unaffordable housing in recent years. While this is difficult to quantify and estimates can vary considerably, accounting for suppressed household formation is an important piece of the supply gap puzzle.

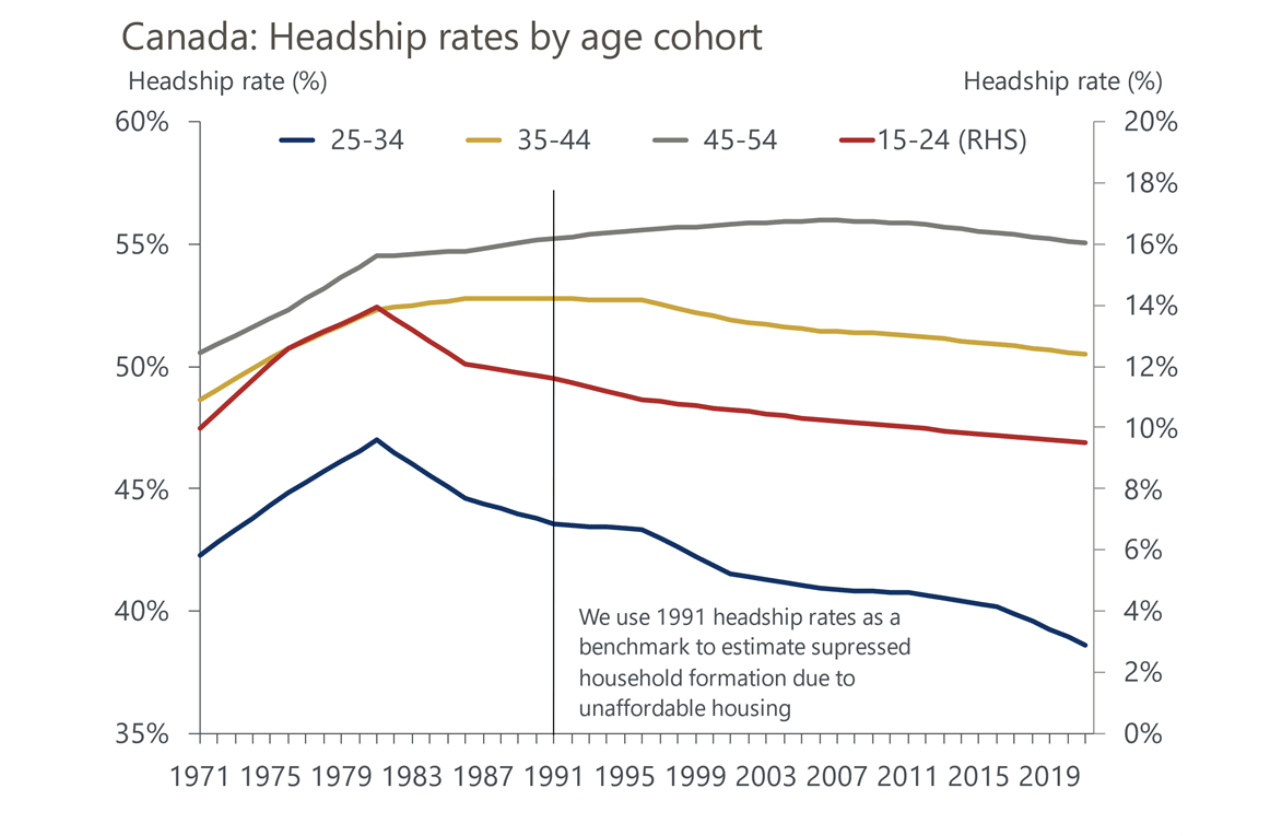

We use higher historical household headship rates for the ages 15-44 from 1991 as a benchmark to calculate how many households haven’t formed due to unaffordable housing (Chart 5). Headship rates for this age cohort actually peaked a decade earlier, but some of the decline since 1981 also reflected secular trends that delayed the forming of households by younger cohorts, like lengthier periods in post-secondary education, as well as the high cost of housing. We estimate there will be about 600,000 suppressed households by 2035. This is well aligned with recent estimates by the Parliamentary Budget Officer but far below national figures implied by the Smart Prosperity Institute’s estimates for Ontario.

Chart 5: Canadians are forming households at lower rates, partially due to unaffordable housing

Source: Oxford Economics/Haver Analytics

Source: Oxford Economics/Haver Analytics

How many homes need to be built to restore market balance?

Canada needs to build enough houses to keep up with underlying demographic demand, achieve a national vacancy rate that is consistent with a balanced and affordable housing market, and make up for suppressed household formation. We estimate this amounts to 4.2mn new housing units between 2024-2035 (Chart 6):

- 2.9mn units to account for household formation, along with demolitions and net conversions.

- 700,000 units to return the national vacancy rate to its long-term equilibrium level, which accounts for continued growth in short-term rentals, second homes, and underused/vacant dwellings.

- 600,000 units for suppressed household formation due to persistently unaffordable housing.

Chart 6: Canada needs to build 4.2mn homes to restore affordability at the national level by 2035

Source: Oxford Economics/Haver Analytics

Source: Oxford Economics/Haver Analytics

How many homes will be built over the next decade?

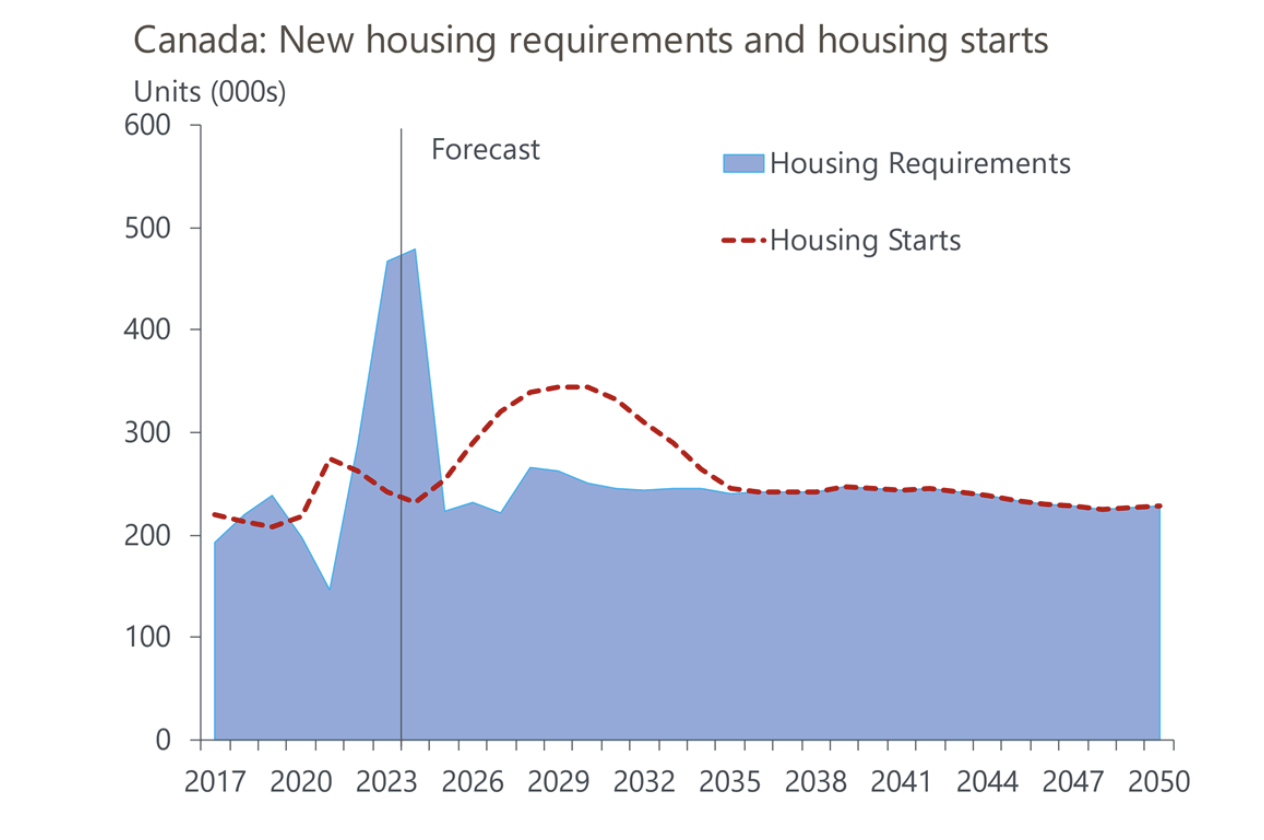

After hitting a cyclical low in late 2024, we expect housing starts will pick up materially in 2025 and through the remainder of this decade as interest rates ease, economic conditions improve, elevated building costs normalize, demographic demand remains strong, and government/industry measures to boost supply take hold. We forecast housing starts will steadily rise from around 230,000 in 2024 to a peak of 345,000 in 2029, resulting in the completion of about 3.6mn new housing units between 2024-2035. This means housing starts will have to average around 300,000 annually through 2035, which is historically high but within the capacity of Canada’s home building, according to the CMHC (Chart 7).

While this means growth in housing supply will more than keep up with growth in demographic housing demand and help limit price growth over the next few years, it will remain short of what is needed to make up for past shortfalls and to rebalance the housing market. As a result, we think persistent undersupply in Canada’s housing market will continue through the remainder of this decade, helping to keep house prices out of reach for typical Canadian households.

Instead, we think it will take another decade before Canada’s housing market returns to balance and affordability to be restored. We expect the 3.6mn new housing units built between 2024-2035 will lift the national vacancy rate to its long-term equilibrium level of 9%. Beyond 2035, a sustained affordable housing market will result in the gradual release of 600,000 suppressed households over time. Accordingly, our forecast assumes total housing starts will increase in line with growth in underlying housing requirements and a steady flow of suppressed households to keep the national vacancy rate stable at its equilibrium level of 9% in the long run.

Chart 7: Housing starts will surpass requirements in the medium term, gradually closing the supply gap

Source: Oxford Economics/Haver Analytics

Housing supply will outpace demand, keeping price growth in check

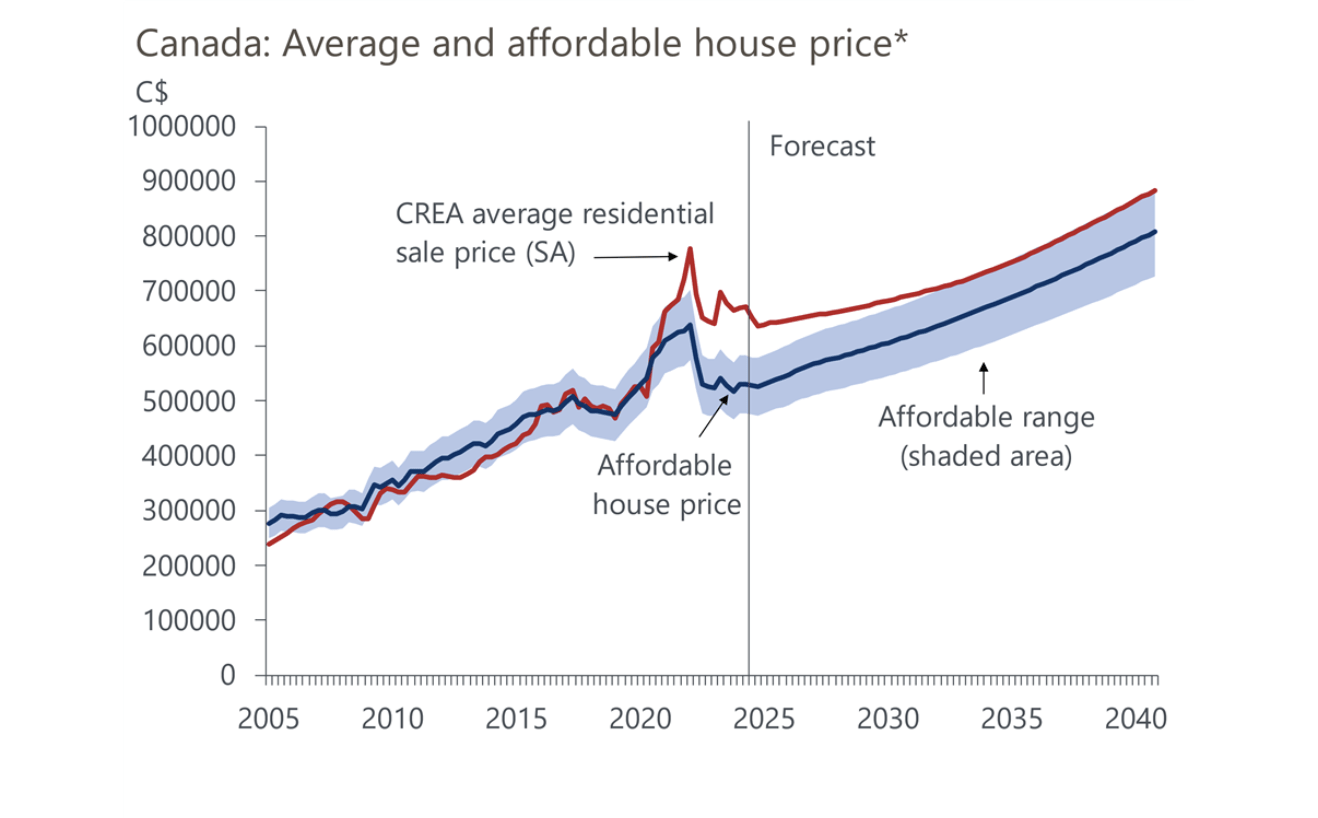

Stronger growth in the housing supply than housing demand will help to keep house price growth in check over the next decade, with national average house prices forecast to rise by less than median household incomes. Accordingly, our Housing Affordability Index (HAI) is forecast to fall from its current unaffordable level of 124 to 109 by the mid-2030s, just within the top of the 90-110 range that we consider to be affordable (Chart 8).

Chart 8: Average house prices will slide just within an affordable range by the mid-2030s

Source: Oxford Economics/Haver Analytics * Affordable house price calculated using median household income and assuming 20% downpayment, 39% gross debt service ratio, 5-year mortgage rate and 25-year amortization period.

Source: Oxford Economics/Haver Analytics * Affordable house price calculated using median household income and assuming 20% downpayment, 39% gross debt service ratio, 5-year mortgage rate and 25-year amortization period.

Importantly, there are a couple of key reasons we expect housing affordability will only barely ease to within the top end of our affordable range in the long run. We suspect that significant regional variations in housing affordability across Canada will be only partially addressed by households relocating to more affordable communities. Also, we expect the average-priced home will remain out of reach to local median-income households for the foreseeable future in some markets, notably the Greater Toronto and Greater Vancouver Areas.

Comparison to CMHC and the PBO supply gap estimates

While our analytical frameworks differ in some respects, we have tallied up our estimate of the number of homes needed to restore affordability over the 2021-2030 period to compare to the housing supply gap estimates produced by the CMHC and Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO).

Between 2021-2030, we estimate Canada needs to build 3.7mn houses to restore affordability at the national level, including 2.6mn to keep up with growth in household formation and a cumulative 1.1mn to remedy suppressed household formation and to return the vacancy rate to a normal level, after accounting for STRs and underused housing.

Our 1.1mn estimate is well below the 3.45mn new homes that CMHC thinks are needed on top of household formation requirements to restore affordability by 2030. Our estimates are more in line with that of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, which estimates around 900,000 dwellings need to be built on top of household formation from 2024-2030 (Chart 9).

Chart 9: We believe only 1.1mn additional homes are needed above demographic demand by 2030, one-third of what CMHC estimates

Source: Oxford Economics/CMHC/PBO

Unintended consequences of building 3.5mn houses

We have some key concerns regarding the massive potential addition to Canada’s housing supply that CMHC promotes. First and foremost, building 3.45mn homes above household formation over the next six years would require a pace of new home building that greatly exceeds even the top end of the CMHC’s own estimates of the construction sector’s capacity. With this in mind, we look at a scenario whereby the economy adds the 3.45mn homes on top of household formation by 2035, half a decade later than CMHC’s aspirational 2030 target.

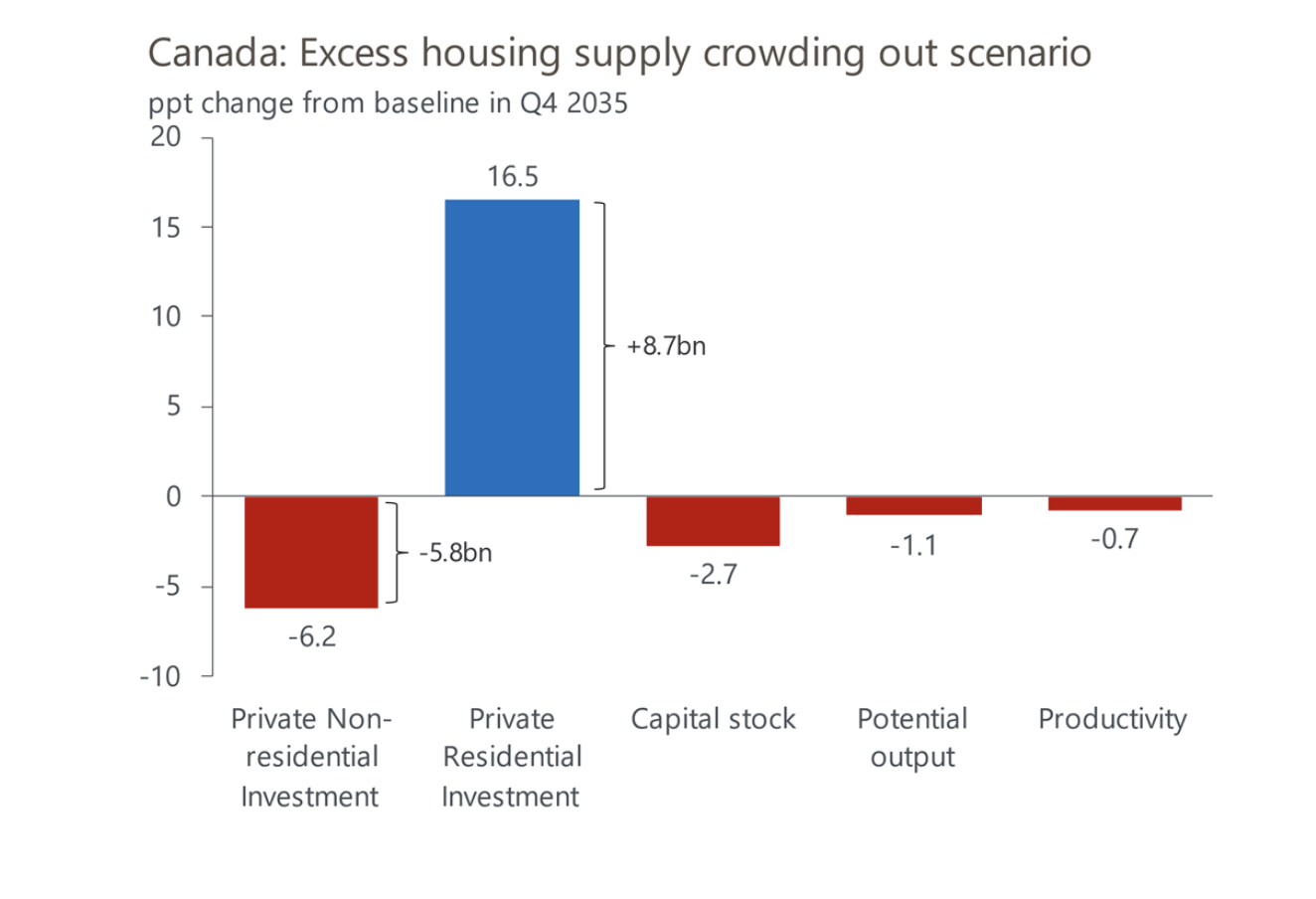

We used our Global Economic Model to assess the economic implications of building this many new residential dwellings by 2035. Devoting such a large share of resources to housing construction risks crowding out private capital investment in more productive industries and hurting Canada’s long-term productivity growth, competitiveness, and economic potential.

In this scenario, we assume that each dollar of additional new residential investment crowds out 67 cents of baseline private non-residential investment (i.e., machinery & equipment, structures, and intellectual property products). Canada’s capital stock would grow at a slower average annual pace of 1.7% between 2024-2035, 0.3ppts below our baseline forecast. As a result, the capital stock would be 2.7% smaller by 2035 than in our baseline. Slower growth in private sector business investment would also hurt Canada’s already lacklustre productivity growth, reducing the level of labour productivity in 2035 by 0.7%. In all, weaker growth in the capital stock and slower productivity growth would shave 0.1ppt annually off potential output growth during this period. Consequently, Canada’s potential economic output would sit about 1% below baseline by the end of 2035 (Chart 10).

Chart 10: Building too many homes would crowd out business investment and weigh on potential output

Source: Oxford Economics/Haver Analytics

Source: Oxford Economics/Haver Analytics

Moreover, if Canada were to build the 3.45mn homes on top of household formation that CMHC is calling for, it would cause the national vacancy rate to approach 20% by 2035. This would be a severe overcorrection from the current state of undersupply to oversupply in the housing market and raise the risk of a substantial correction in residential property values in the longer term, especially as an aging baby boomer population begins selling and bestowing their homes.

Aging seniors tend to sell or bequeath their homes around the same time they consider moving into assisted living or nursing homes, typically in their late 70s to early 80s. Our demographic projection shows mortality for seniors aged 75-85 years as a share of the overall population will steadily rise through the 2030s before peaking around 2040. So, overly excessive additions to Canada’s housing supply in the 2030s could be exacerbated by a wave of homes passed down from aging seniors.

Another key consideration is the static versus dynamic reality of singularly focusing on boosting supply to address housing affordability, especially for vibrant, global cities like Toronto and Vancouver. Even if enough housing can be built to meet current and future demand, it may only provide a temporary reprieve in affordability due to the induced demand to live in attractive locations, just like widening a road initially cuts congestion but ultimately attracts more vehicles until congestion returns. Although this induced demand effect will likely keep major Canadian cities like Toronto and Vancouver unaffordable in the long term, we still think additional housing supply is needed to help restore affordability at the national level by the mid-2030s.

Tony Stillo is Director of Canada Economics at Oxford Economics and Michael Davenport is an Economist at Oxford Economics.