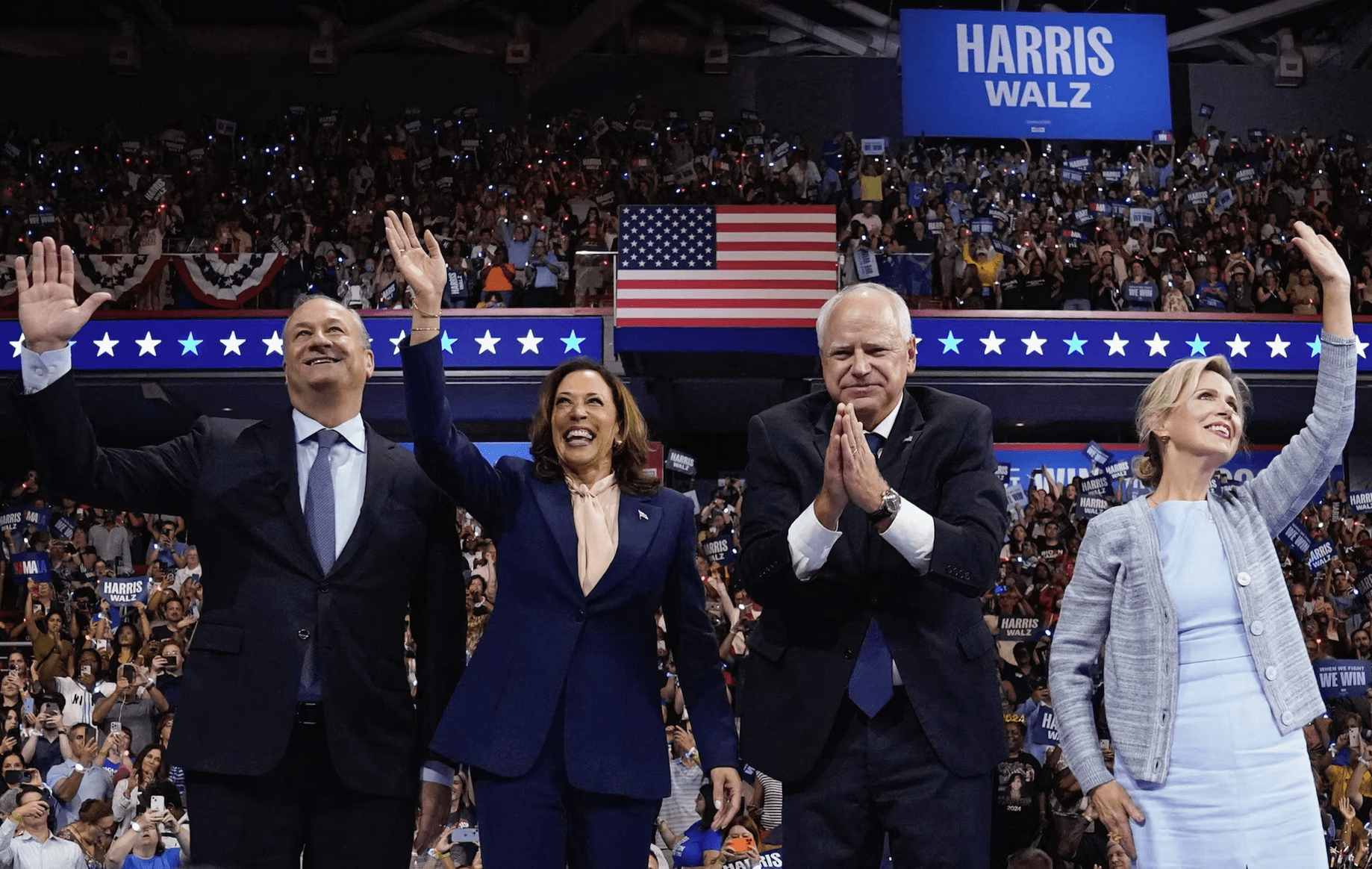

The Democrats Conquered the Incumbency Curse. Can Canada’s Liberals do the Same?

Reuters

Reuters

August 17, 2024

It was just a few weeks ago that the prospects for progressive governments in North America were trending in a similar downward direction. And perilously so. If there were wake-up calls necessary for just how bad it might be for both President Joe Biden and Prime Minister Trudeau, both parties received them at full volume. Biden’s barely coherent June 27 debate performance against an unhinged but resurgent Donald Trump sent the Democrats’ campaign into a tailspin.

As for Trudeau’s Liberals, the results of the Toronto-St. Paul’s by-election three days earlier, a loss in what had been a Liberal stronghold, seemed to confirm what the dreadful poll numbers had been signaling for months. In both instances, party faithful were compelled to go through that ritual of ensuring message discipline was strictly observed, and that the most, um, colourfulresponses to these five-alarm incidents stayed behind closed doors as much as possible.

However, political crises are always the most trying when they will have a direct impact on who’ll be coming to the office with banker’s boxes the week after E-day. Neither of these was an internal crisis – Biden’s debate performance registered in real time, worldwide, on live television, and a bad byelection night cannot be downplayed as a gaffe. Above all, message discipline tends to evaporate at the water’s edge where quotability meets lack of attribution. Inevitably, stories will surface that include the phrase “sources within caucus say,” or “senior party officials say” as, in Ottawa and Washington, the phones of Bob Fife and Peter Baker trill and trill with calls coming from inside the house.

The most corrosive agent to the party brands from such events is the perception of a kind of willed inaction at the very top of the org chart. Regardless of whether this is perception or reality, such defining moments require that the issue be treated with the same tactical considerations as those that have a greater impact on the public at large. Nobody expects immediate solutions to crises, but questions tend to cease when there is a carefully considered process in place to get to one, and it is communicated clearly.

Maybe leadership mattered less than how these parties might effectively combat the momentum behind ‘Make America Great Again’, ‘Axe the Tax’ and ‘Britain Needs Reform’.

Both Biden’s Democrats and the Liberals here were having difficulties getting to the safer shores of process answers to manage these crises, however. Days passed for the Democrats with the slow-drip effect of op- eds and statements from celebrity supporters calling for Biden to step aside. The pile-on continued with carefully worded tweets and posts calling for urgent action from those whose influence still carried weight within the party. A similar effect gained some momentum initially here in Canada with a few former ministers and current caucus members declaring the Liberals’ downward slide in the polls was about the PM more than anything, and that he had to go.

But nobody within the Liberal party seemed to have thought through what kind of process answer could at least serve to put this brush fire out (one regular outlier from Liberal caucus messaging, Nathan Erskine Smith, offered one by way of a kind of a plebiscite involving all party members, but that went nowhere quickly). The official response in the aftermath of Toronto-St. Paul’s seemed to be something about listening to constituents and disaffected former Liberal voters and then … reflecting. Those were the outputs; outcomes TBD.

Another question loomed beyond one of party leadership, however: were both the Democrats and Liberals facing something larger, a surge of right-wing populism rising around the world, not just in North America? If this were indeed the case, maybe leadership mattered less than how these parties might effectively combat the momentum behind “Make America Great Again”, “Axe the Tax” and “Britain Needs Reform”.

PA

PA

Events since then have shed further light on these questions, however, and they point to a conclusion that’s resonating stronger by the day. But first, let’s look at the events themselves..

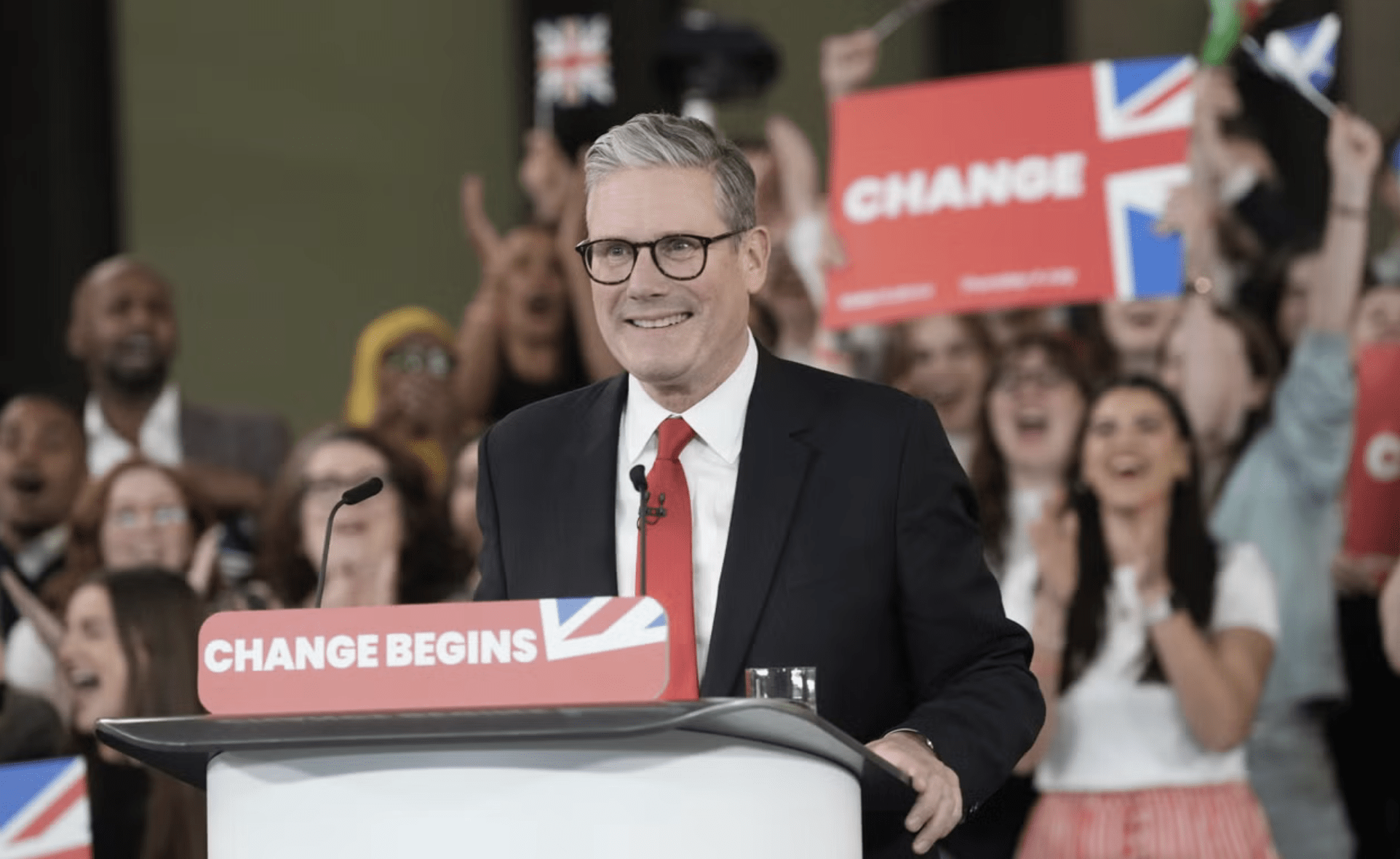

The victory of Keir Starmer’s Labour Party in the July 1 UK general election was, on face, the strongest argument in support of the claim that it’s about the populism, stupid (or about the stupid populism, if you like), and that if the Democrats and Liberals here were to take on that phenomenon effectively, all would be well.

Anne Applebaum, writing in The Atlantic, outlined what she believed was Starmer’s winning formula:

“He pushed back against a wave of anti-Semitism, removed the latter-day Marxists, and eventually expelled Corbyn himself. Starmer reoriented Labour’s foreign policy [pro multilateralism, full support for Ukraine] … and above all changed Labour’s language. Instead of fighting ideological battles, Starmer wanted the party to talk about ordinary people’s problems—advice that Democrats in the United States, and centrists around the world, could also stand to hear … ‘Populism,’ Starmer told me Saturday, thrives on ‘a disaffection for politics. A lack of belief that politics can be a force for good has meant that people have turned away in some cases from progressive causes.’”

However, critics of Applebaum’s piece noted, soon after, that the support for Starmer’s government could be considered qualified at best: popular vote share only increased two percent since the Corbyn days. And indeed, the sectarian violence and disinformation campaigns triggered by the Southport murders have already tested the mettle of Starmer’s government – a clear signal that no progressive government will be immune from textbook destabilization tactics favoured by anti-democracy forces around the world. Indeed, the jury’s still out on the UK’s qualified support for Starmer’s Labour movement, and the same challenges of “broken-ness” that disaffected, former five-minute Liberals see as a failing of Trudeau’s time in office loom just as largely for Starmer – as they have for Biden, of course.

Incumbency is more than just a stigma; it’s emerged as the fundamental challenge of governments that bear the scars and road miles of the pandemic years.

Which is an appropriate segue to the second event: the Harris-Walz reinvigoration, rebranding, indeed reinfusion of Obama-era energy into the Democrat presidential slate. In a matter of days, it eclipsed the panic and disunity of Biden’s final days as the presidential candidate.

If Harris does manage to pull a victory off on election day, thesis papers will be written about this remarkable turnaround, but it is already clear what her campaign has accomplished masterfully: it has not only made the central challenge of incumbency irrelevant, it has effectively plagued the Trump campaign with that stigma.

Indeed, incumbency is more than just a stigma; it’s emerged as the fundamental challenge of governments that bear the scars and road miles of the pandemic years. Biden’s fragility only made his presence on the campaign more evocative of those before-times. Trump’s maundering incoherence has served to transfer that dark lockdown mantle onto his padded shoulders. Rishi Sunak could not put up much of a fight against it in the UK; no bold campaign platform or strategic foregrounding of any star players were going to scrub away the brand corrosion the party accumulated, both during and since Johnson’s time as PM.

But with Harris and Walz, they were virtually undefined at a national level, it seems. That’s shocking enough, given Harris’s role as VP over the last four years, but it probably shouldn’t be, given that low information voting remains a significant factor for any federal campaign. Both Harris and Walz filled the open space for definition with such a marked contrast to Trump (with Walz notably “reading” as Republican with initial research), and they reinfused the Democratic brand with youthful energy, a burgeoning hope agenda and “the politics of joy.” It is still early days, but they have scrubbed much of the party’s brand corrosion clean, leaving Trump to flail in increasingly outrageous ways as he tries to figure out what might stick to them.

And so, heading into the last year-and-change before a federal election here in Canada, this seems to be the formidable challenge for Trudeau’s Liberals: how do you read to voters with all of the energy required to heave off your shoulders the weight of incumbency, and to scrub clean brand corrosion? To activate anything similar to Starmer’s formula to defeat right-wing populism, that will be job one? It’s going to require something big, something decisive. Though, as the UK example suggests with the Tories, brand corrosion might be a more complex issue to grapple with than a simple switching out of the leader could solve.

This much is certain, however: It’s going to require something more than listening, reflecting or waiting for Canadians to see how much like Trump Poilievre allegedly is, how sunny Tiff Macklem sounds (eventually) or how “weird” Conservatives are.

Contributing Writer John Delacourt, Vice President at Counsel Public Affairs in Ottawa, is a former director of the Liberal research bureau. He is also the author of four novels, including his latest, Provenance, about the Nazi looting of European artwork, and The Black State, a political thriller.