Policy Dispatch: Doing the Time Warp in the Real Transylvania

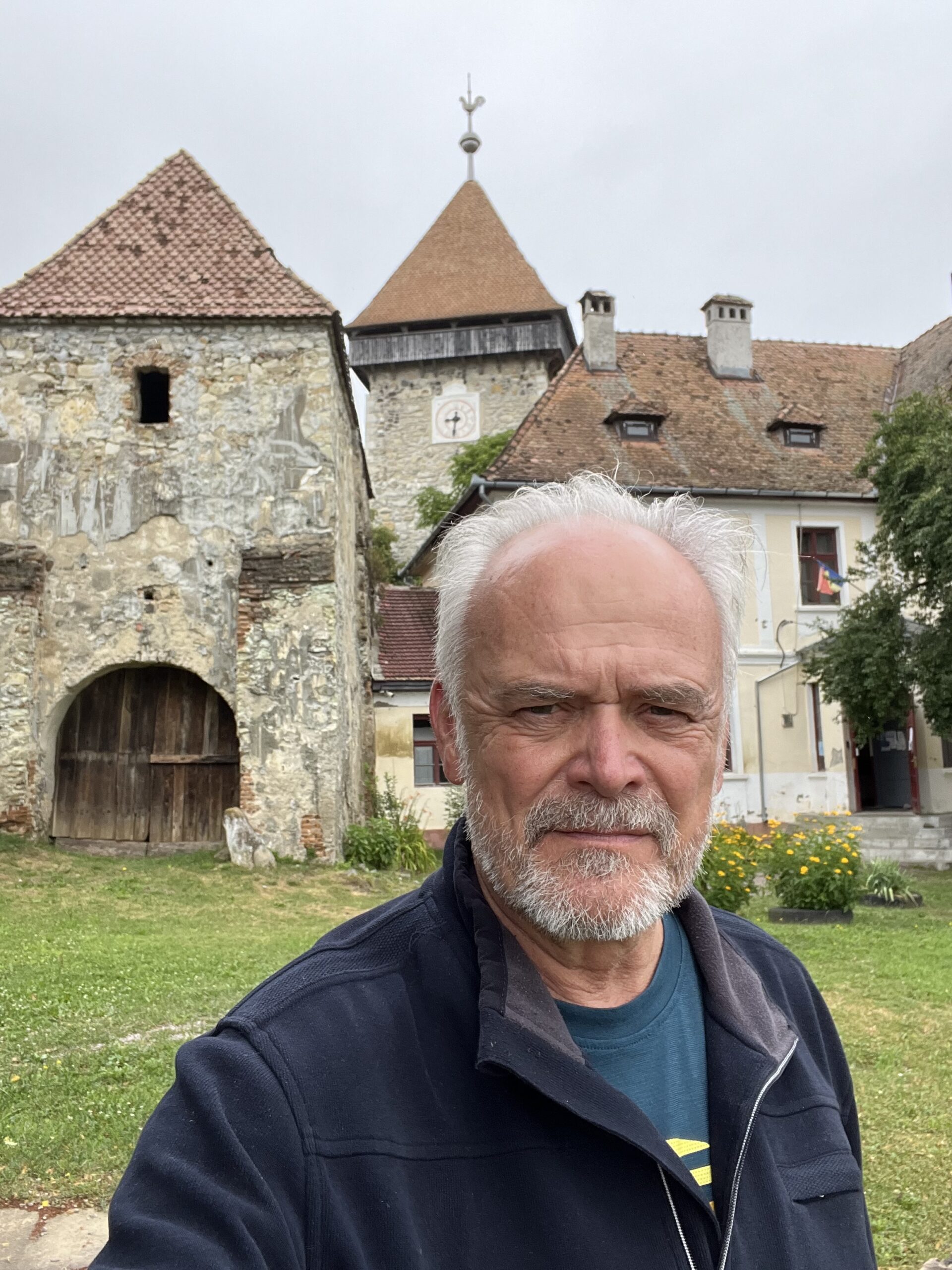

The author in his mother’s Transylvanian home town of Draas

By Peter M. Boehm

July 15, 2024.

Most of us, at some point in our lives, take an avid interest in our roots: who our ancestors were, where they came from, how they lived. As a child of refugees and a first-generation Canadian, I am no exception.

My roots are with the Saxons of Transylvania, now part of Romania, who emigrated in the Middle Ages from what today is Luxembourg and the Mosel area of Germany, lured by free settlement land offered by King Géza of Hungary, formalized in the Diploma Andreanum of 1224. Transylvanian Saxons are a people of mostly German ethnicity, who speak a German dialect known as Siweberjesch Såksesch or just Såksesch.

While Canada’s Transylvanian Saxon minority may not have the high profile or cultural footprint of our Italian, Chinese or Afro-Caribbean counterparts — the Transylvanian-Saxon diaspora, for instance, does not have the political clout of the Irish or Indian diasporas, and there’s no category for Transylvanian restaurants in the Michelin Guide Canada — we do represent a language and culture with a deep, fascinating, and often misunderstood story. Bram Stoker’s Dracula and The Rocky Horror Picture Show are, each in their own way, masterpieces, but the misconceptions they’ve fed about Transylvania can be hard to dislodge, to say nothing of the countless vampire and transvestite jokes I’ve heard — some funnier than others — at parties and in G7 meetings over the years.

I know about the real Transylvania because, like so many Canadian children, I had that “old country” history, its customs, language and mores drilled into me by my parents, who, while embracing their new Canadian identities following the chaos and horrors of the Second World War that caused them to flee with their families (they met in Canada), spoke of their ancient homeland with much affection and vivid memory. Indeed, I am still a member of the Transylvania Club of Kitchener-Waterloo.

So, when participating this month as a member of the Canadian delegation at the Parliamentary Assembly of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) in Bucharest, it seemed only natural to add on a trip to Transylvania. I had been there before: once with my parents as young teenager in 1969; with a bunch of friends coming out of Austria in a camper van in 1976; and with my family while serving in Berlin as ambassador in 2010. Every experience was unique, emotional and difficult to describe.

Professionally, I visited Romania on my early assignment as a desk officer in what was then the Soviet and Eastern European Division of the Department of External Affairs. My specific file was nuclear cooperation, and our CANDU reactors in Romania are still producing electricity today, with a major refurbishment and expansion project just inked between our countries.

On this trip, Bucharest impressed me. The Romanian economy is doing well and there is a sense of confidence in the air, despite the war to the north in Ukraine. Such an assessment would have been unthinkable during my time all those years ago on the Romania desk.

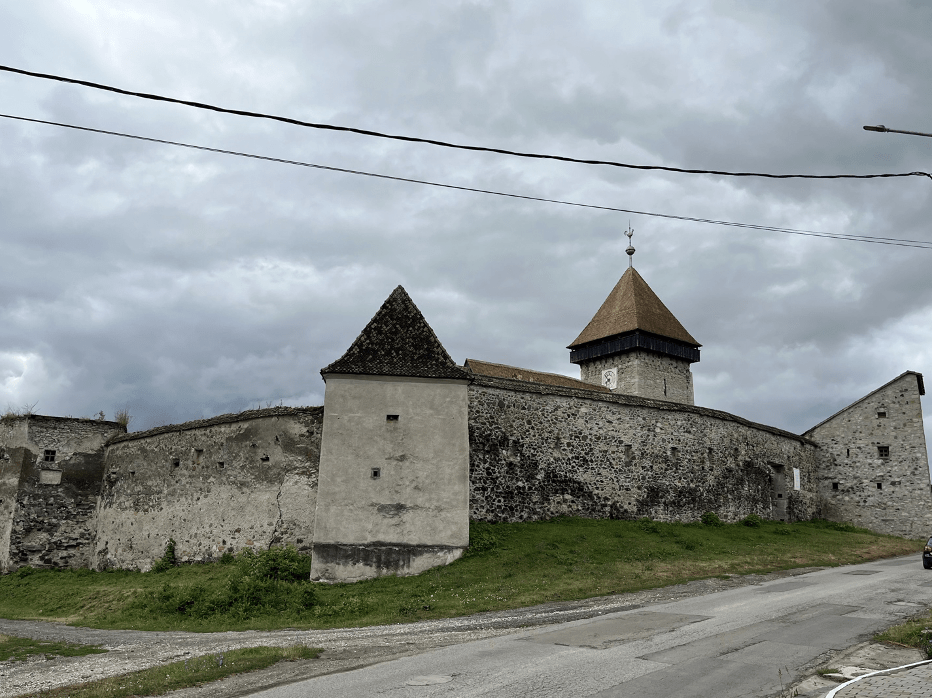

Following the OSCE conference, my spouse, Julia, and I rented a small SUV and drove north through the heat and sometime thunderstorms, through the Carpathian Mountains, past fortresses, castles and through sweeping vistas to the small Saxon village of Viscri (Deutsch Weisskirch), famous for being a traditional farming village with a 13th century fortified church. There are more than 150 such unique fortified churches in Transylvania, built to withstand invasions and raids by the Ottomans, Wallachians and assorted Central European groups so many centuries ago that they reinforce that sense of time warp you feel in a place where so many things have remained unchanged.

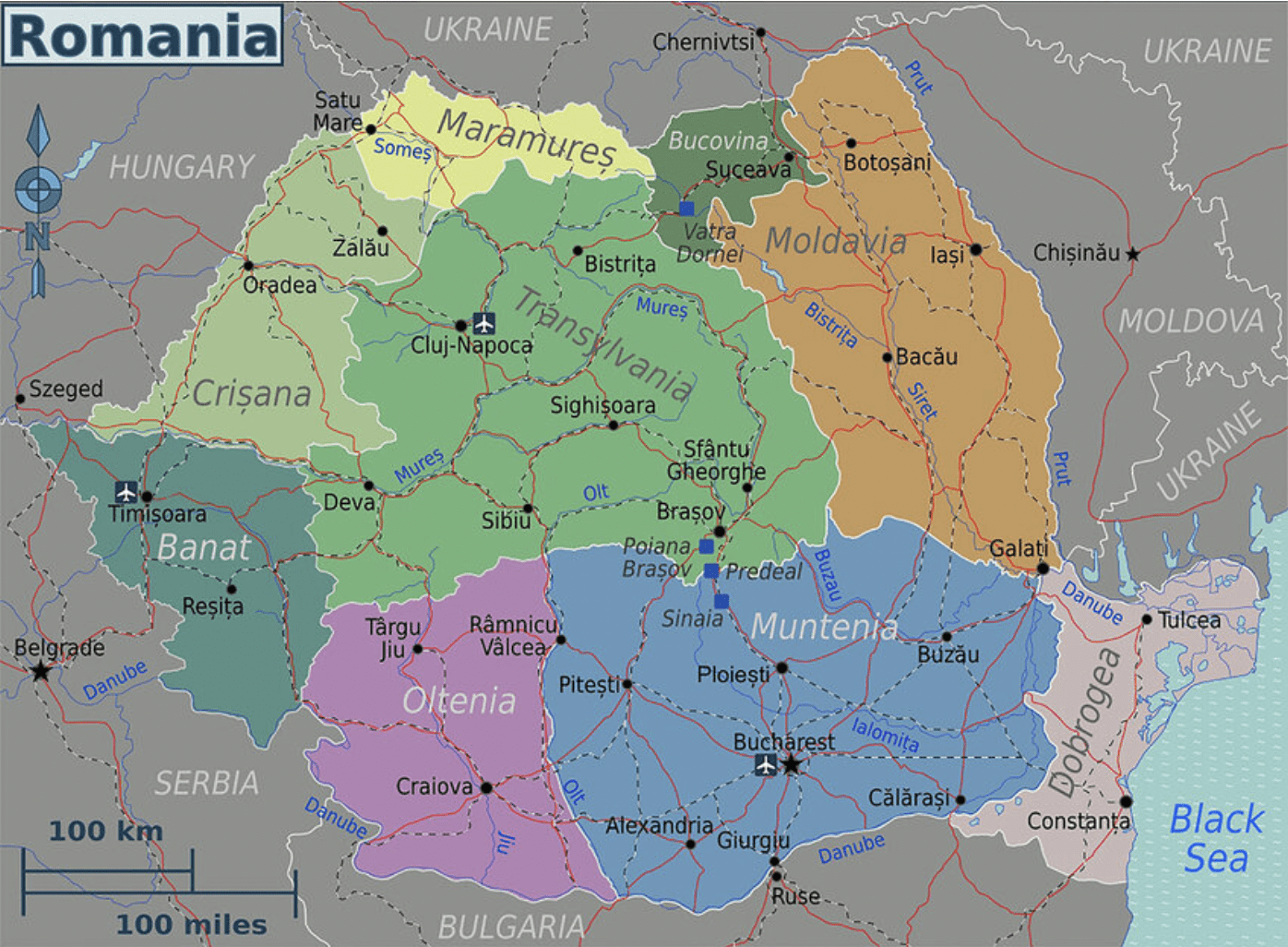

King Charles at his property in Viscri in June, 2023/Framey

King Charles at his property in Viscri in June, 2023/Framey

Viscri’s more recent claim to fame is as the Transylvanian village that then-Prince Charles fell in love with when he visited in 2006, prompting him to purchase a rambling farmhouse as a nature retreat. That property has since been converted into a guest house and training centre for traditional crafts and rural skills, under the auspices of the Prince Charles Foundation Romania, established in 2015.

The royal connection remains strong. Indeed, Charles’ second foreign visit as king in 2023 — right after addressing the German Bundestag — was to Romania, and he visited Viscri yet again.

For our visit, we stayed in a converted farmhouse, explored the village, watched the cattle and goats come home from the fields at the end of the day (they all knew where they lived) and explored the church and its battlements.

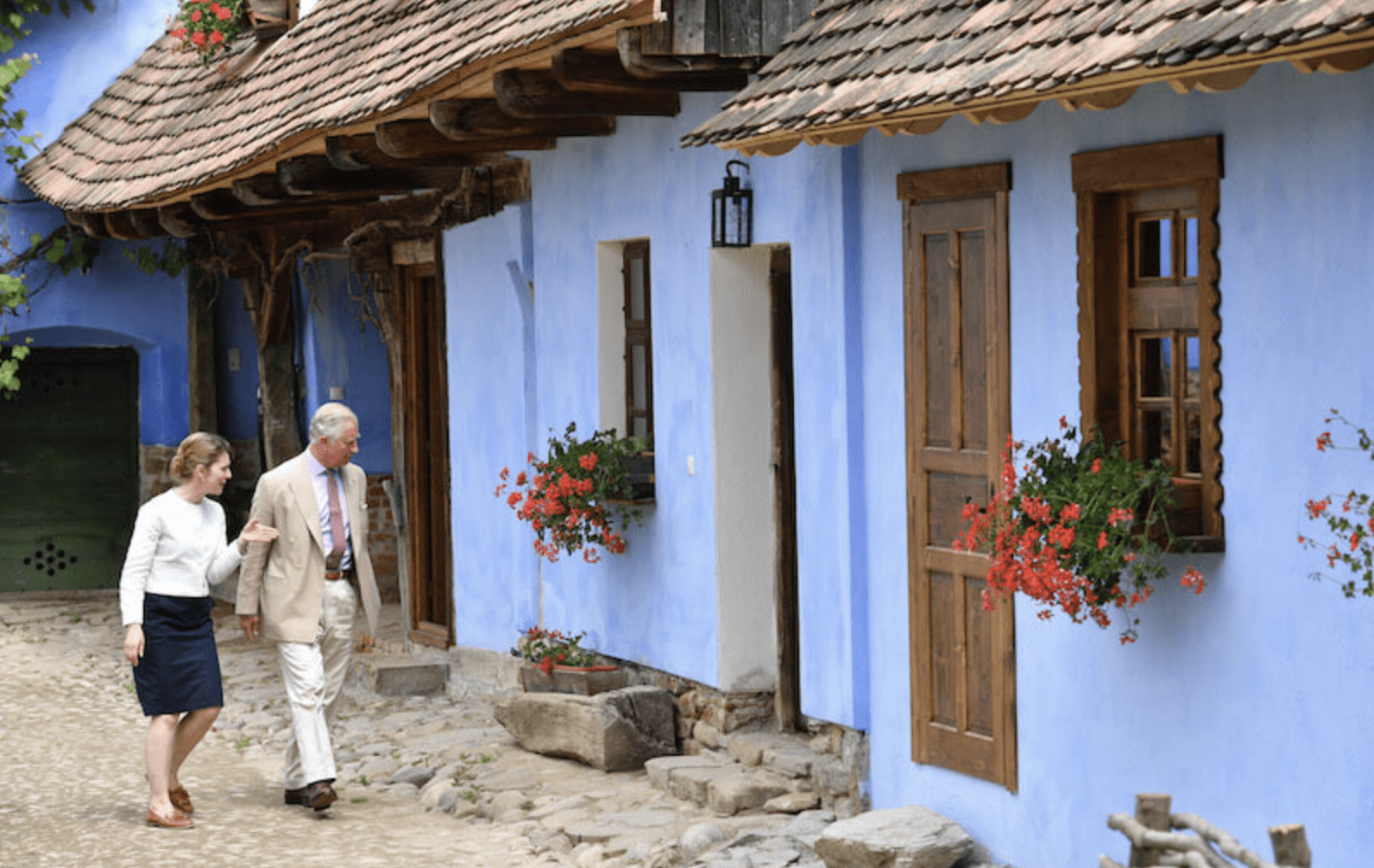

The fortified church in Draas/Peter Boehm

The fortified church in Draas/Peter Boehm

My mother’s home village of Draas (Drăușeni on tourist maps) was some twenty kilometres away over the hills. Its own fortified church has UNESCO designation but is in need of repair; with only one elderly Saxon woman, Ella Kosa, remaining in the village, the church no longer serves its religious purpose; its uniquely painted pulpit, altar and baroque organ having been moved to other churches in Transylvania, its reliquary items to museums. Walls were exposed as part of the renovation, exposing frescoes dating from Catholic times. These had not been seen for centuries, since they were plastered over during the Reformation, but not before the fervent villagers used their hammers on the saints’ faces.

Ella Kosa produced an authoritative history of the village — one that I already knew, from the local history Draas Through Time, written by my maternal grandfather Michael Markus, and his brother Johann. My grandfather had been Draas’s trilingual (German, Hungarian, Romanian) mayor. (Growing up, I once asked my grandfather why, with the many languages he knew, he preferred to swear in Hungarian. He said it was the “juiciest” language for that purpose). We also visited the village cemetery: the Saxon part where my maternal ancestors were buried is in a state of complete neglect, overgrown, with headstones broken and sunken into the ground.

Transylvania’s nesting storks/Peter M. Boehm

Transylvania is a popular home for storks. Their impressive nests rest on light standards, chimneys and rooftops. When we visited, the large juveniles were making their first efforts to fly and would emit beak-clacking symphonies when they sensed their parents were arriving with food. Soon they will all be off to Africa.

We continued our travels to Sighișoara (Schässburg), a perfectly walled and preserved medieval town that still has a small Saxon community and impressive churches and cemetery. It is very much a tourist draw, including for Romanians who continue to discover their own multilingual and multi-ethnic country, an opportunity denied them until the revolution of 1989.

The walled Medieval town of Sighisoara/Peter M. Boehm

Sighișoara is also the purported birthplace, in 1431, of the notorious Vlad the Impaler, the brutal military governor of Walachia said to be the inspiration for Stoker’s Dracula. And yes, its many attractions also include a “Transylvania Escape Room” (what better location?), which we chose not to try.

Romanians love driving fast, especially on mountain roads. While they are waiting to pass, they are so close that you sense their presence in your back seat. On the serpentine mountain roads it is no surprise to find a large truck barrelling around a corner towards you in your lane. Even though I’m a bit of an aggressive driver myself, we drove the quieter back roads, stopping at a few more of Transylvania’s fortified churches before reaching Sibiu (Hermannstadt), the impressive former Saxon capital.

The historic Transylvanian Saxon capital of Sibiu/Peter M. Boehm

Part of the city’s walled fortifications and bastions remain, its two old city plazas attest to a storied past, although one featured a beach volleyball tournament with sand and raised seating for fans. Sibiu is known as the city “with eyes” as its attic dormer windows have that appearance. Romania’s president, Klaus Iohannis (of Saxon heritage) was a popular mayor here. I remember speaking with him in the Transylvanian Saxon dialect at a nuclear security summit in Washington in 2016. We received some strange looks, especially when former European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker joined us, speaking compatible Luxembourgish. Not bad after nine centuries.

In reflecting on one’s roots and ancestry, it is easy to overthink, to be emotional, if not maudlin. Is this really where my ancestors are from? What ties me to them other than my parents? What were they like? There are only some 12,000 Transylvanian Saxons remaining in Romania, a dramatic decline from more than 200,000 at the beginning of the 20th century. Many departed after the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1919, seeking their fortune in the United States, Europe and Canada. More fled in September of 1944 as the Soviet army advanced through Romania. Many of those who remained were taken to Russian labour camps; not all returned. Others were part of a deal made in the late 1960s by dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu that permitted emigration through convertible currency payment (chiefly from Germany).

Many of the last generation saw their opportunity to go west when the communist regime collapsed completely in 1989. Some have returned. They were farmers, craftsmen, artisans and scholars, rigid in their ambition to maintain their language, religion and largely rural way of life. Their fortified churches remain as testimony, ironic in a sense in that these people were drawn to Transylvania to establish a strategic bulwark at the eastern end of an empire. Etched into the stonework of many of the churches is Martin Luther’s axiom: “Eine feste Burg ist unser Gott” (“a mighty fortress is our God”). So it was.

I look forward to telling my mother all our stories from Transylvania when we celebrate her 96th birthday later this month.

Sen. Peter M. Boehm, a regular contributor to Policy magazine, is a former senior diplomat and current chair of the Standing Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade.