France’s Election: A Good Night for the Left, a Bad One for Le Pen, and a Mixed Bag for Macron

The election night crowd at Place de la République/Reuters

July 7, 2024

Quelle soirée.

From panic over the likely takeover of French politics by Marine Le Pen’s far-right Rassemblement National (National Rally), France has swung to the democratic left instead. The strategic voting undertaken by the Nouveau Front Populaire (New Popular Front) — formed on the left among the Socialists, Greens, Communists and Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise — and President Emmanuel Macron’s Ensemble centrist party, repelled the threat from the far right.

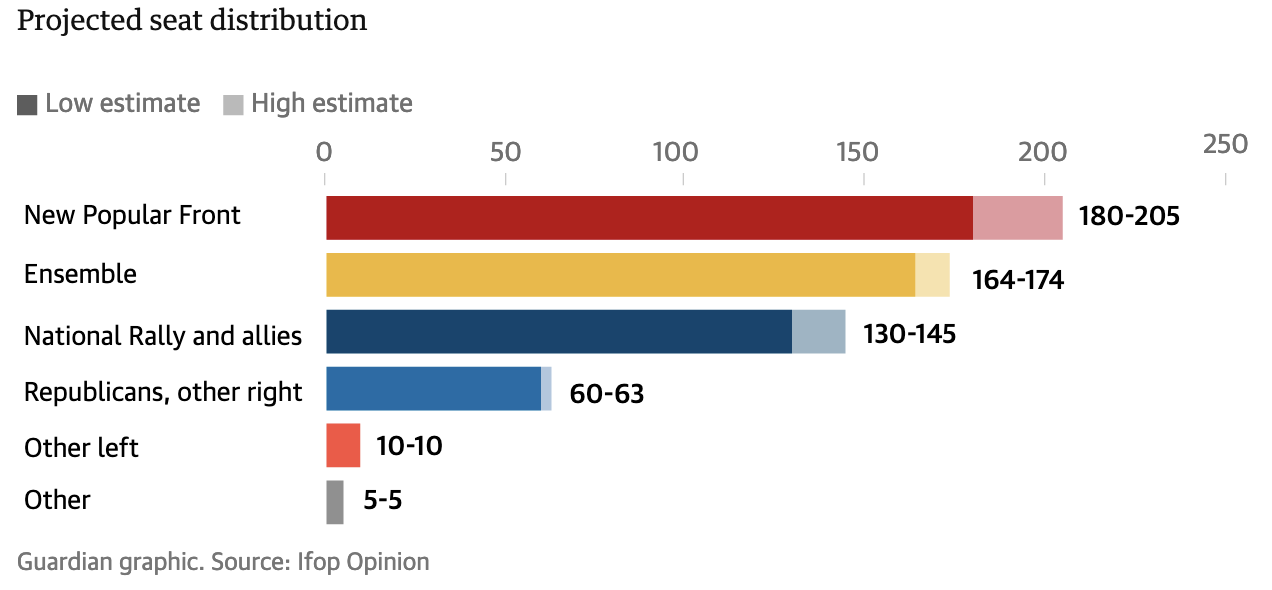

At press time on election night, the Nouveau Front Populaire is projected to win between 180 and 205 seats in France’s Assemblée Nationale, ahead of Macron’s coalition (between 164 and 174) and the far-right Rassemblement National (between 130 and 145).

It’s tempting to say that Macron’s gamble in dissolving parliament after the right-wing surge in last month’s European Union elections got it partly right, after seemingly getting it wrong based on subsequent polls and the RN lead in the first round of voting on June 30. In the end, his own alliance came in second, behind the rather remarkable NPF, whose barrage against the National Rally worked like a charm, relegating Le Pen to third place.

Macron is a big thinker who addresses the problems and challenges of a decade hence. He believes, like Kier Starmer, who has won a big victory in Britain by moving his party to the centre, that the moderate middle is where solutions to society’s biggest challenges can be found. The centre is where compromise lives.

But Macron knows that his country is profoundly divided. The left and the right appear each more extreme today and stronger than when he was elected President in 2017 as a centrist. Neither the left not the right could reach a majority alone, and Sunday’s legislative elections confirmed it. The extreme right had been on the rise, but tonight has been cut off at the knees.

So, who are the winners? I dare say, democracy; both for voter turnout unseen in four decades (an estimated 67% at this writing), and for thwarting a broader anti-democracy threat. And combined with Keir Starmer’s Labour victory in the UK, the democratic liberal and inclusive political groupings in Europe.

The centre has not been a legislative winner, but nor has it lost. We’ll see how negotiations to produce a French government work out, but Macron has to have heard the message to move closer to the democratic left.

Before Macron made his remarkable run in 2017, there was already an enduring post-war centre in French politics, represented on the centre-right by the Republicans, whose most recent President was Jacques Chirac, and on the centre-left by the socialists, whose most recent President was Francois Hollande — elected Sunday as the député from Corrèze. Macron cheekily broke up their duopoly, ending the comfortable “alternance.”

Public enthusiasm vaulted Macron into power and crumpled the two establishment parties. Macron’s big-picture project succeeded on many levels, reducing inflation and unemployment, cutting energy costs, boosting technology and inward investment. He became the EU’s visionary for a stronger Europe, tried to intercede with Vladimir Putin, gave it up, and became Ukraine’s unconditional champion.

France always had a divide between urban – especially Parisian – elites and sophisticates, and citizens in rural areas and small towns where TGV rail doesn’t go, and where age-old traditions such as boulangeries and boucheries are being replaced by modernism, hollowing out town centres. But lately, that divide has been angrier and more potent than before.

Macron wanted to secure France’s state pension regime by raising eligibility from 60 to 64 and France’s working class went haywire. It also exploded over taxes on petrol, launching the gilets jaunes protests that paralyzed Paris on Saturdays for a year.

Macron’s entitled style aggravated the sense of alienation, the belief that “les gouvernants” in Paris had no comprehension of life’s challenges for their humbler and angry “gouvernés.” Macron’s party began to lose voters to the extreme right and the radical left. Both are Euro-skeptical, anti-élite, and against pension reform, but Le Pen’s National Rally was singularly hostile to immigration — a popular scapegoat — and encouraged its identification with a new brand of belligerent populism embraced by Donald Trump and other fearmongers.

National Rally President Jordan Bardella on election night/Reuters

National Rally President Jordan Bardella on election night/Reuters

The RN blamed immigrants for French job loss, for welfare fraud, and for diluting the French family and traditional values. Le Pen herself stood back and appointed 28-year-old Jordan Bardella president of her party in order to attract younger voters, which he did via Tik-Tok, with some success. Until Sunday’s coup de foudre result, Bardella had been touted as France’s next prime minister. (On election night, he attributed the party’s loss to an “alliance of dishonour”).

Meanwhile, Macron’s concept of “radical centrism” lost its appeal.

As Yeats warned in the aftermath of the Great War, in The Second Coming:

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Macron had conviction to excess but lost his ability to channel it to the people. Passionate intensity can be difficult to sustain amid the grinding rigours of daily governing, and youth and newness are the hardest attributes to maintain as time wears on, facts that ate away at Macron’s approval ratings. With their own passionate intensity, both the nationalist right and the left challenged Macron’s personalist rule. French society appeared fractured between the two, though Le Pen’s far-right seemed to be gaining momentum, threatening a charge on government itself. It was an illusion, though national polls seemed to validate it. The RN doubled its score tonight, but France has reverted to the centre-left.

Overall, this is good news for France, and for Europe — that France is not veering to the nationalist right, as the US did with Trump, Hungary did with Orban, or the UK did when it went for Brexit.

History matters. France has a century-long history of left-right cycles in parliament. In 1936, the rise of fascist right-wingers prompted the creation of the original Popular Front government under Socialist Léon Blum as an alliance of the left to counter the extreme right. Blum, who was Jewish, was eventually defeated by conservatives, extradited to Germany by the Vichy government during the war and imprisoned in Buchenwald. This may seem like ancient history to some North American readers, but as William Faulkner once said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Charles De Gaulle returned to liberated France in 1944 as the head of a transitional government awaiting a new constitution to replace the discredited Third Republic, whose quarrels among parliamentary parties paralyzed government. In 1946, when legislators in decided on a Fourth Republic that more or less resembled the Third, De Gaulle, who wanted a strong executive branch, walked (having told Canadian Ambassador Gen. Georges Vanier he was thinking of going to live in Canada for a time to recover — a fine irony in light of his 1967 disruption).

The Fourth Republic also failed, as France wound down its empire with losing and murderous wars in Indochina and then fatefully in Algeria. When they turned again to De Gaulle to return, he insisted on an executive branch strong enough to permit clarity of national governance despite parliamentary egotisms (including that of the strong Communist party, at one point with 30% of the vote).

A chastened Macron must now bend to govern with the democratic left, writes Kinsman/AP

Macron wanted to preserve that executive prerogative, which he believed was threatened by the rise of the extreme right. In calling a snap election to counter the RN, Macron hadn’t anticipated the left would unite in an alliance, called, in historically resonant terms, the New Popular Front. Its four parties – the tough left, La France Insoumise, or France Unbowed, under the ferociously aggressive Mélenchon; the remnant of the once-dominant Socialists (who did well in the Euro elections under Raphael Glucksmann; the Greens; and the diminished Communists. The surprisingly-agreed defensive coalition, with an approved slate of candidates, vaulted immediately to a strong second position in the polls, at 28%, not far from Le Pen’s RN at 33%, and way ahead of Macron’s own alliance at 20%.

Electoral math seemed to favour a second-round line-up in most constituencies of the RN vs. the New Popular Front. It suggested the RN couldn’t win a majority of seats and thus form an extreme-right government that would need to work in competitive “cohabitation” with centrist President Macron whose term ends only in 2027. Cohabitation has worked twice in the past, under Socialist President Mittérrand and Republican PM Chirac, and then under President Chirac and Socialist PM Lionel Jospin, but their radius of political positions was much tighter than what would be a polarized and even hostile situation between the RN and Macron. France would have been both polarized and paralyzed.

So, the Popular Front will form the government. We don’t know who the next prime minister will be, but the election-night resignation offer from incumbent Macronian PM Gabriel Attal was rejected by Macron on Monday so that Attal can remain in office while negotiations over a new coalition and PM proceed. (Resistance to Mélenchon in this role is as strong as his brand of aggressive hostility to power). But the fact is that parliament, not the president, will choose the next PM.

A chastened Macron must now bend to share government with the democratic left, which by evidence is much closer than he is to public sentiment today; on the cost of living, the hardship of the daily grind, income disparity, and the eternal wall between Parisian elites and les cols bleus.

But Macron can take satisfaction that he won a showdown with Madame le Pen that ought to dampen her optimism about finally winning a presidential election 2027 (her 7th try).

This is good news for Europe, Ukraine, immigrants, inclusion, and participatory democracy.

And whatever the nuances, it’s a massive relief in France, and far and wide.

Policy Contributing Writer Jeremy Kinsman served as Canada’s Ambassador to Russia, Italy and the European Union and as High Commissioner to the UK. He is a Distinguished Fellow of the Canadian International Council.