Canada and NATO at 75: Enmeshment Diplomacy Redux

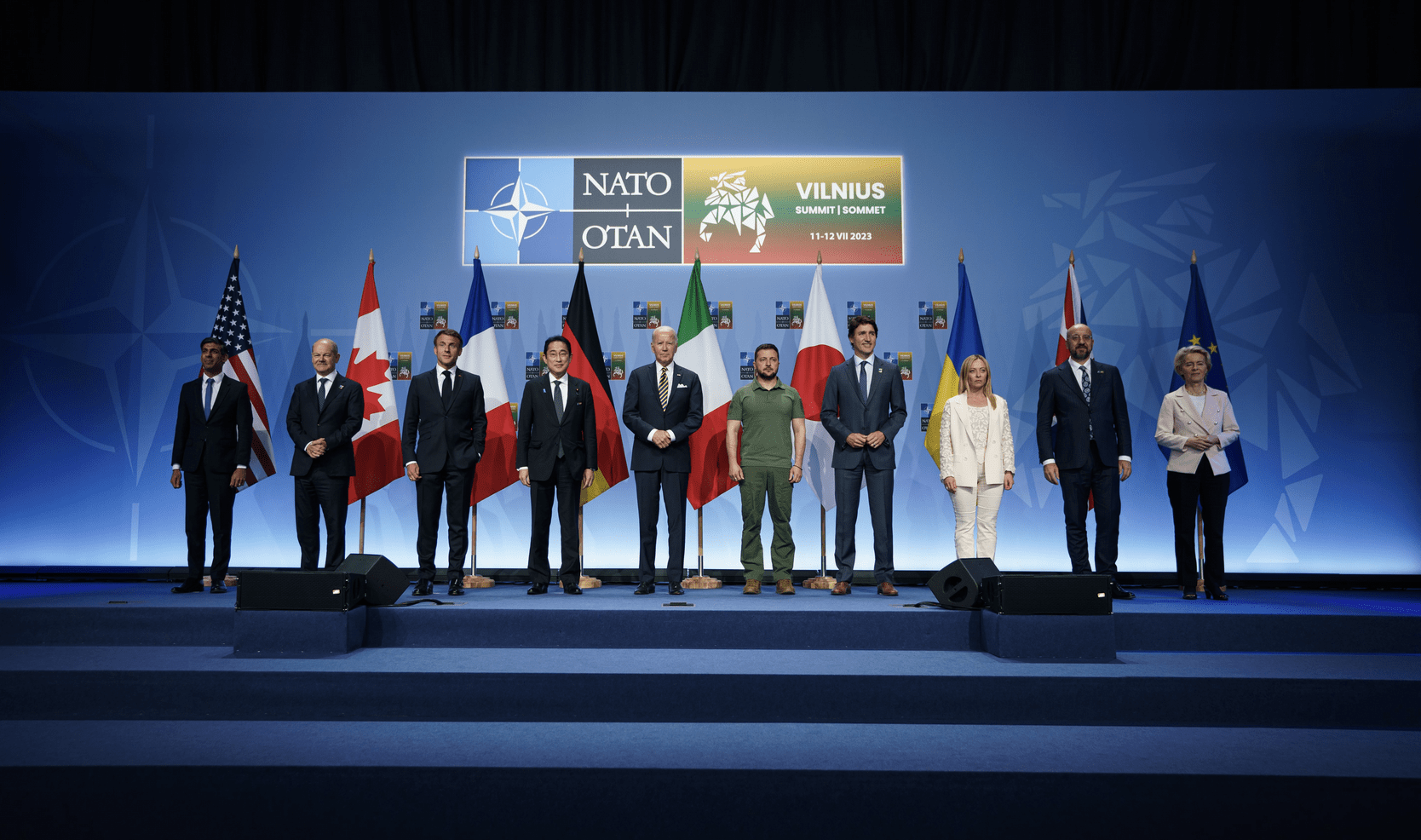

Double diplomacy: The G7 leaders at the 2023 NATO Summit in Vilnius/Adam Scotti

Double diplomacy: The G7 leaders at the 2023 NATO Summit in Vilnius/Adam Scotti

Michael W. Manulak

July 3, 2024

As we mark the 75th Anniversary of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), uncertainty hangs over the alliance. In a world of increased division and danger, questions concerning the United States’ commitment to its allies threaten NATO’s credibility. If Donald Trump is elected president for a second time, will he fulfill U.S. obligations to allies or deliver on his threat to withdraw from the alliance altogether?

The implications of these questions for Canada are enormous; how would we respond? Seventy-five years ago, Canada faced similar dilemmas and responded with a focused and determined strategy of diplomatic enmeshment vis-à-vis the U.S. The past offers lessons for today.

Looking Back

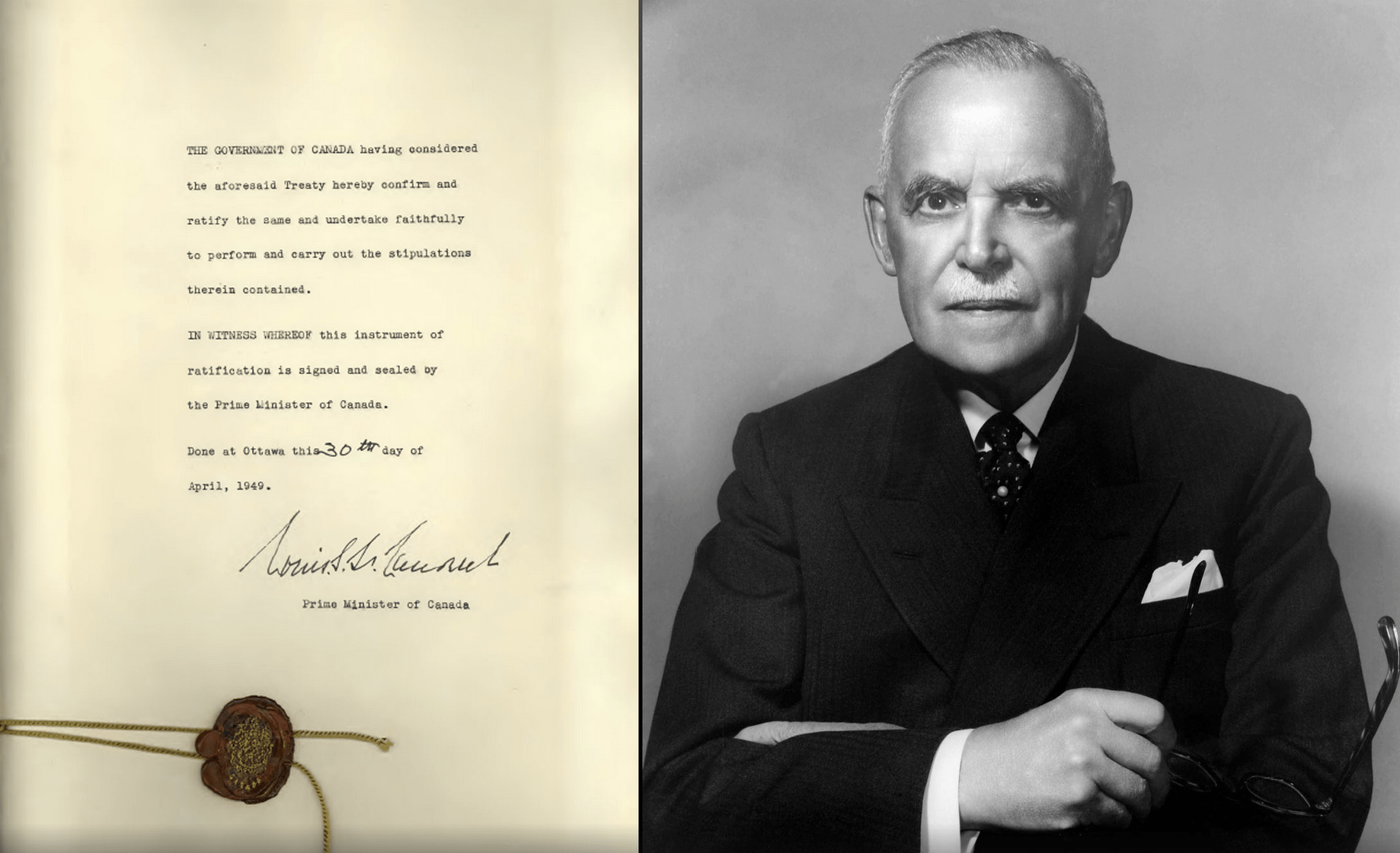

Canada’s accession to NATO, signed by Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent, 30 April 1949/NATO archive.

Canada’s accession to NATO, signed by Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent, 30 April 1949/NATO archive.

Rather than a period of stability, the end of the Second World War saw a new and dangerous phase of geopolitical competition. U.S.-Soviet tensions paralyzed the United Nations Security Council, the organization created just months before to maintain international peace and security. The Soviet Union had swallowed up much of Eastern and Central Europe. Communist activities in Greece, Italy and elsewhere, as well Soviet intimidation of Norway, alarmed Ottawa. Exhausted and broken from the war, Western Europe was unable to counter the threat alone.

Looking south, Canadian officials feared renewed isolationism in America. The U.S. had avoided any firm post-war security commitment to Europe despite its unparalleled economic and military might. Many Americans wanted, again, to put America first, reflecting a belief that other countries should take care of their own security.

Yet, as Canadian diplomats realized sooner than most, this U.S. posture risked a repeat of the experience of the World Wars. American power now needed to deter aggression in Europe, rather than countering it after wars erupted. In his September 1947 UN General Assembly address, Canada’s foreign minister, Louis St. Laurent, argued that democratic countries might be forced to bolster their security through accepting “more specific international obligations” within the framework of the UN Charter.

It was the first public statement of the sort by a Western leader and was received internationally with considerable interest. As the Paris-based American journalist and author Don Cook later reflected: “If the Canadians could perceive the need for North America to join an Atlantic pact, could the Americans lag far behind?”

Canada came to pursue what I have elsewhere termed a “diplomacy of enmeshment”; a deliberate strategy seeking to ensure that the U.S. remained firmly linked—and indeed central—within the network of rules, norms, and institutions of the international system.

St. Laurent’s speech provided a backdrop that, combined with a shocking communist coup in Czechoslovakia, triggered secret tripartite American-British-Canadian talks in March 1948. These discussions, led on the Canadian side by Lester B. Pearson, then Undersecretary of State for External Affairs, produced a first basis for the North Atlantic Treaty. Rather than a unilateral U.S. declaration or an American/Canadian accession to the recently concluded “Brussels Pact” – options explored by U.S. officials – Pearson advocated deeper security cooperation.

Following these discussions, talks progressed slowly, owing to internal debates within the State Department and to U.S. domestic politics. Canadians worried that momentum had been lost and sought to get discussions back on track. As a British diplomat later reflected: “While the Americans appeared to be going backward, the Canadians moved forwards with the courage that they would display throughout the negotiations.”

On 29 April 1948, St. Laurent addressed the House of Commons, calling for collective defence arrangements among democracies. Speaking as much to Washington as to Canadians, he added: “The western European democracies are not beggars asking for our charity. They are allies whose assistance we need in order to be able to successfully defend ourselves and our beliefs. Canada and the United States need the assistance of the western European democracies just as they need ours.”

The speech was soon cited by the British foreign secretary and written copies received wide circulation in Washington. St. Laurent’s remarks were mentioned often to Canada’s U.S. ambassador, Hume Wrong, as he targeted those within the State Department who opposed a binding alliance, including George Kennan. The speech, Kennan conceded in a memo, added “a new and important element.”

Canada’s primary aim was clear: to push for the strongest possible U.S. security guarantee for Europe, keeping the U.S. firmly engaged in the world in the belief that an inward turn by Washington threatened international security. Canada would mobilize its best diplomatic resources to enmesh the U.S. in a binding treaty.

As talks moved into 1949, they took an unexpected turn: the chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Senator Tom Connally, demanded last-minute changes to the draft treaty text, significantly weakening what would become NATO’s all-important Article 5. Again, Canadian diplomats responded. In expressing Canadian concern with the new U.S. draft, Pearson authorized Wrong to make a strong case, going as far as threatening Canadian withdrawal if the weaker text were retained. “It is better,” Pearson asserted, “to have no treaty at all than to have one that is so weak and ambiguous as to be meaningless and therefore mischievous.”

After some creative internal maneuvering, the U.S. revised the pledge again, meeting both Connally’s hesitations and the wishes of Canada and its other negotiating partners.

While Canada had also made headway in drafting Article 2, the so-called “Canadian article” on social and economic affairs, and in multilateralizing NATO’s Military Committee, no Canadian contribution to forging the alliance was as significant and lasting as helping to ensure a strong Article 5.

Looking Forward

Canada’s recently appointed ambassador to NATO, Heidi Hulan/Manfred Werner-Wikimedia

Canada’s recently appointed ambassador to NATO, Heidi Hulan/Manfred Werner-Wikimedia

Canadian influence in the North Atlantic Treaty negotiations owed to the postwar credibility of its military and the calibre of its ideas and diplomatic representation. Canada pursued a strategy of enmeshment, seeking to keep the U.S. firmly linked – and indeed central – to a multilateral global order.

With growing questions today concerning the U.S. commitment to that order, Canada must rediscover this focus. Indeed, few things matter more for Canada’s security than helping to maintain U.S. engagement within NATO. If the U.S. wavers, for instance, allies may seek to bolster their security through other means. The implications, including for the nuclear non-proliferation regime, are considerable.

A strategy of enmeshment via NATO is not an endorsement of military friend-shoring. It should be pursued alongside reinvestment in the United Nations and engagement with countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. It also cannot be done on the cheap.

Canada must mobilize its best foreign policy minds and recognize that being a good ally does not require the government simply to follow the American lead. This was true 75 years ago. Now, as then, the U.S. does not seek supplicants. Canadian interests will not always line up with American ones. This is the case on nuclear disarmament, for instance, where Canada has historically maintained pressure on the U.S. to limit the role of these dangerous weapons. Importantly, while advancing its own interests vis-à-vis the U.S., Canadian diplomats have often found supportive constituencies within the U.S. system.

Finally, in Washington for the alliance’s 75th anniversary, Canada should announce a timeline for reaching NATO’s 2% spending commitment. Not doing so compromises Canada’s position at the NATO table, including its capacity for influence on global security. By strengthening the hand of Canada’s new NATO ambassador, Heidi Hulan, and other leading officials, Canada can do its part in keeping the U.S. enmeshed within the alliance, and in a position of power in the world order it has led for the past 75 years.

Policy contributor Michael W. Manulak, an Associate Professor at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs of Carleton University, holds a doctorate in International Relations from Oxford University. He served in the Government of Canada from 2015-2019, mainly within the Department of National Defence, representing the government internationally in proliferation security negotiations.