Policy Q&A: Karl Moore on why Ambiverts Make Better Leaders

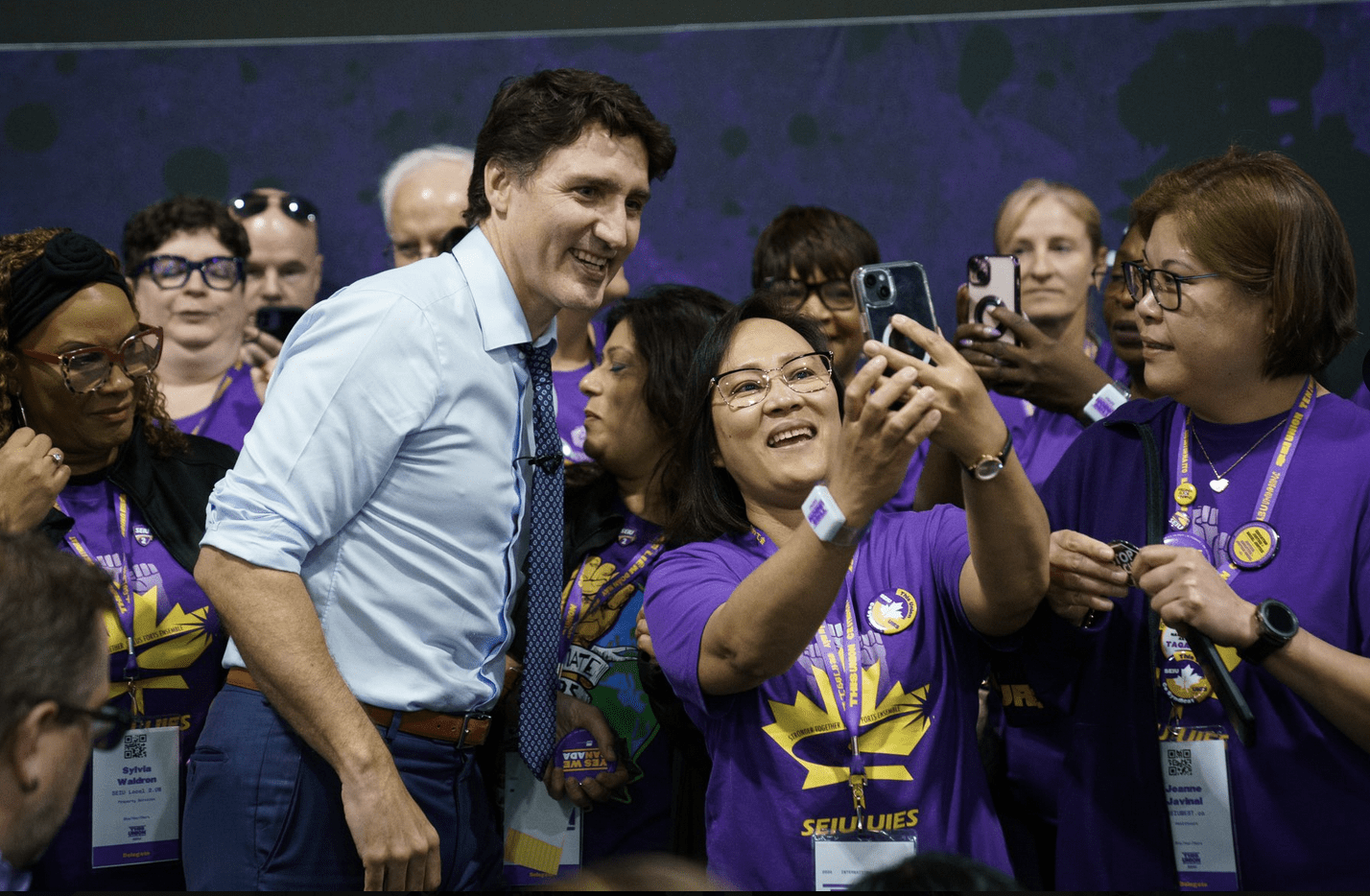

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who self-identifies as an introvert but works like an ambivert/X

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who self-identifies as an introvert but works like an ambivert/X

Policy contributor and McGill management professor Karl Moore has spent years interviewing Canadian and international business, political and military leaders for his CEO Series radio show and podcast. Those interviews have informed his research on introverts, extroverts, ambiverts and leadership. His upcoming book, We Are All Ambiverts Now, explores the benefits of balance when it comes to leadership and temperament. Policy editor Lisa Van Dusen conducted the following Q&A with Karl Moore.

June 14, 2024

Policy: You’ve spent years interviewing Canadian and international CEOs. How important do you think introversion, extroversion and ambiversion (mix of both) are in the mix of leadership skills that produce success or failure?

Karl Moore: It has been over a decade that my research team and I have been looking at introverts, extroverts and ambiverts as leaders in the executive suite. What our interviews with many executives suggest is that clearly, it is an old-school view that only extroverts are excellent leaders. We are taking a more nuanced view these days. The working title of our soon-to-be-released book is We Are All Ambiverts Now. An ambivert is someone who acts like an introvert at times and an extrovert at other times, depending on the context and what is the appropriate and most useful leadership approach.

The key idea is that an introvert very much likes people, but after a fair bit of stimulation must recharge their batteries with introvert breaks. On the other hand, extroverts seek out stimulation, and when they don’t have enough of it, recharge with extrovert breaks, where they seek out stimulation. In longitudinal research by Jerome Kagan and Nancy Snidman at Harvard for their book The Long Shadow of Temperament, they recorded four-month-old babies’ responses to stimulation. They followed those babies for more than two decades and it was a reasonable, not perfect, predictor of whether they would be more introverted or extroverted as adults, suggesting it is to some fair degree based on our DNA.

CEOs can be all over the bell curve that is extroversion, ambiversion and introversion. It depends a bit on the industry and the role of that CEO at the place of the evolution of the firm. There is an old expression, “horses for courses”, sometimes you need a change-oriented CEO, other times someone who will allow a firm to take advantage of a business model that is in sync with the times. But a general principle is that CEOs should aim to be ambiverts: sometimes use the typical skills of an introvert and be a great listener, allow others to be the centre of attention, be more one-on-one in their networking and conversations; and other times, act more like an extrovert — give a more stirring speech to rally the troops, to be someone anyone feels comfortable approaching and be at ease in large groups of employees and other stakeholders.

So, our research strongly suggests that introverts can be outstanding leaders in many industries. In some industries, some roles lend themselves more to the introversion.

Policy: Business leaders don’t have to sell themselves to voters as a flesh-pressing proposition — is it easier to succeed as an introvert in business than in politics?

Karl Moore: Business leaders in big organizations do have to sell their corporate vision and strategy to employees around the world, their own senior management, big shareholders, Bay Street and Wall Street analyses, etc. They typically spend far more time selling the strategy than coming up with the strategy. So not entirely different from politicians but you’re right that politicians have to have a retail side to their work.

Particularly during election campaigns, when they go door to door, address voters, campaign workers and media on a daily basis. And once they are elected, senior politicians have got to meet with the members of the caucus, interact with other leaders, both political and business, and continually woo voters — the next election is never that far off. This is very typical extrovert behaviour but by doing it more one-on-one or in small groups it can be a bit easier for the introvert.

Policy: You’ve concluded that the best leadership approach is ambiversion — combining the qualities of introverts and extroverts for a sort of Goldilocks approach — sounds simple, but can people really change that easily? Aren’t the reasons why we fall into one camp or the other — introvert or extrovert — hard-wired through nature and instilled through nature?

KM: We are arguing that senior leaders, which very much includes politicians, should act like an ambiverts, that is act like an extrovert in many of their tasks, but if you are introvert, you must be true to your DNA and take regular introvert breaks to recharge. From a number of interviews with politicians, we found that they agree that you have to act like an introvert at times when comes to policy, have deeper relationships with people in order to be an excellent politician, so it cuts both ways.

It is not a matter of changing but rather asking for a bit of, not too much, flexibility. And not everyone can do or indeed wants to do it. In a company there are many people who do the work of organization, think engineers at WSP, programs at CGI, or the many bankers who put together the important details of a deal, a loan, or a lawyer who creates the right contract. There are only so many senior leaders required, those roles are different, many seek those spots, few reach them and a considerable majority realize over time they really don’t want that kind of pressure and are content to deliver the lower-profile work of the organization. So, though all must be somewhat flexible, it’s only the more senior leaders that must really adapt, and they learn to do it over a number of years. If they hate it, they drop out of the race.

Policy: In shifting your focus to presidents and prime ministers in this book, can you give us a sense of where some fit on the introvert/extrovert/ambivert spectrum?

KM: A number of the prime ministers in our time have been extroverts, others introverts. Among the extroverts, I suspect I would number Jean Chrétien, John Turner, Paul Martin and of course, Brian Mulroney. Introverts Stephen Harper, Joe Clark, Kim Campbell, and perhaps, surprisingly Justin Trudeau. I have had all but two to class here at McGill or interviewed them one-on-one. The current prime minister clearly told me he is an introvert but acts like an extrovert because that is what the role requires. The great purpose that he is fulfilling in his better moments is what motivates him to act the extrovert part, it is simply the job of a PM at times. But he spoke with enthusiasm about the frequent introvert breaks he takes. I was surprised but he convinced me.

Some U.S. Presidents were/are better at being ambiverts. For my research, I spoke with journalist David Shribman, formerly of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Wall Street Journal, and the New York Times, and who won a Pulitzer while at the Boston Globe for his Washington coverage. In his view, three were ambiverts, Presidents Kennedy, Obama and Clinton. Others were more on the extroverted side — Presidents Johnson, Reagan, George H.W. Bush, George W. Bush, Trump, and Biden came to mind. The extroverts would be more apt to err on the side of dominating rather than listening when it is really is important. The introverts were better on seeking advice and hearing their advisors out. No one can possible remotely be anything approaching an expert on the range of topics that the President must decide on, they must listen and have good judgement as to who’s opinion to lean on.

On the other hand, in order to be elected, they also have to fund raise, to inspire the party faithful, and the other duties of a political leader in the U.S., or Canada for that matter, so a more extroverted approach is called for. When you are the U.S. President, you are the centre of attention in every room you enter, other than the family rooms of the White House. That takes someone who can handle large amounts of stimulation. But as Prime Minister Trudeau pointed out to me if you want to make big changes in the world, to make it a better place you need to suck it up and act like an ambivert, even if you are not one. Not dissimilar to CEOs of large organizations, though the rewards of being President/Prime Minister are greater.

Karl Moore is an Associate Professor at the Desautels Faculty of Management, McGill University. He has taught extensively in executive education and MBA programs, including at Oxford (1995-2000), Stanford, LBS, Harvard Business School, Cambridge, Cornell, and INSEAD, among others. He is a regular contributor to Policy magazine.