Courage and Calvados: The Canadian Correspondents Who Covered D-Day

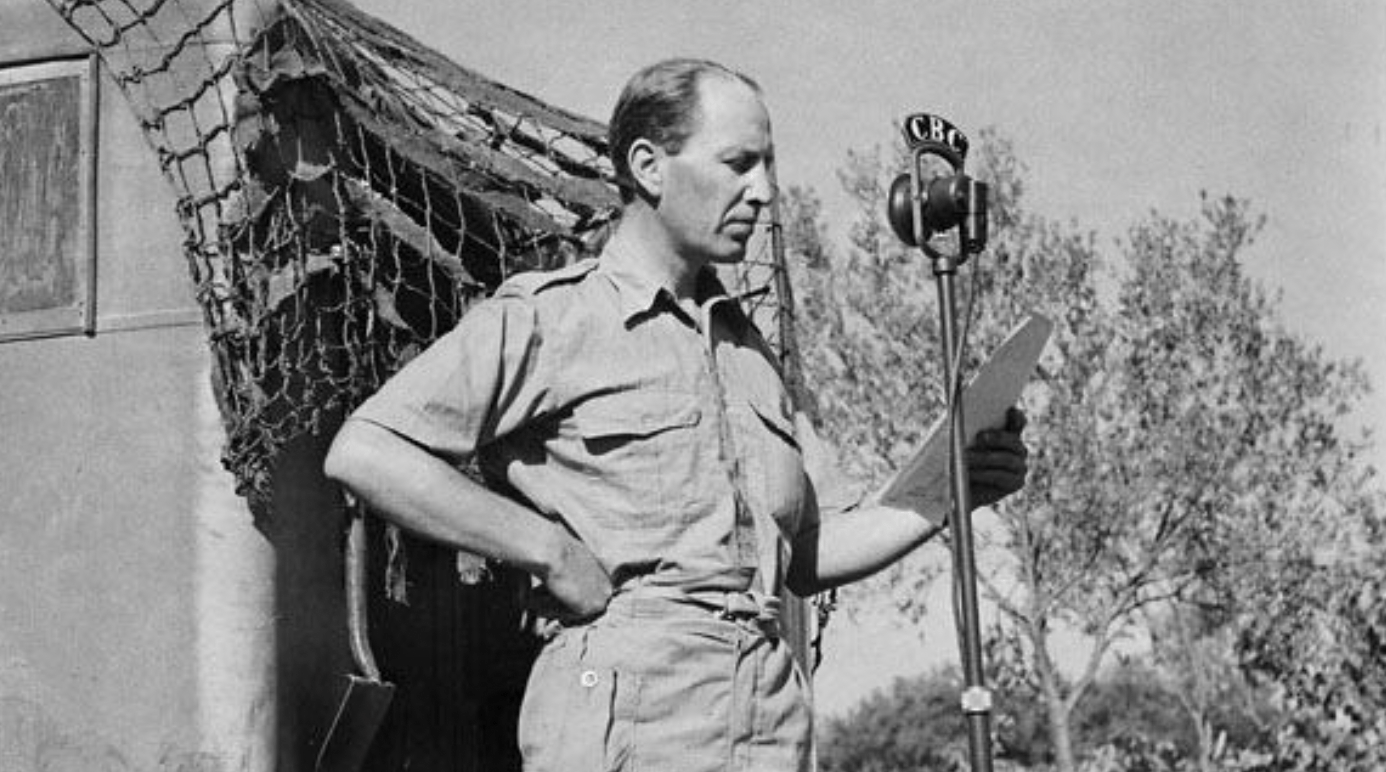

Matthew Halton covering WWII in Europe for CBC Radio (CBC photo)

David Halton’s father, the late CBC foreign correspondent Matthew Halton, often described as Canada’s Ed Murrow, was one of seven Canadian reporters embedded with our D-Day landing forces. David’s riveting biography of his father, Dispatches from the Front: The Life of Matthew Halton, Canada’s Voice at War, was published in 2014.

By David Halton

June 4, 2024

For Canadian war correspondents, D-Day was a time of both tribulation and triumph. It was an exceptionally high-stakes, high-stress assignment. Yet it was Ross Munro, a Canadian Press reporter, who was the first correspondent from any country to have an account of the invasion published from the Normandy beachhead. Other scoops would follow, when the first film and photos of the invasion to be seen in the U.K. and North America were shot by Canadians.

It was also a time of bitter frustration for radio correspondents — including my father, the CBC’s Matthew Halton — who were unable to record the event for another 48 hours.

Only seven Canadian journalists were given the prized opportunity to land with the assault forces. They included battle-experienced veterans such as Munro of CP, Ralph Allen of the Globe and Mail, Marcel Ouimet of Radio-Canada, and my father, already famous for his broadcasts from the front in Italy. They were all under the authority of Brig. Gen. Dick Malone, the Army PR chief who was determined that the Canadian role in D-Day not be overshadowed by the British and American forces.

For two months before the invasion, the seven Canadians and other correspondents became pawns in Allied plans to fool the Germans about when the invasion would take place. In one effort in April, they were ordered to pack their bags and prepare to embark on the biggest story of their lives. Instead, they were taken by train to Scotland, where they were held incommunicado for a week, given some military briefings, and allowed one secret but enjoyable outing to a local whisky distillery. Allied intelligence hoped that their disappearance would be noted by German spies, who’d be both confused and mistrusted in future about the timing of the real event.

For four days prior to D-Day, the so-called “assault correspondents” were sequestered near Portsmouth. They were assigned different ships to take them to Normandy for fear that there would be no one to report the story if they didn’t make it. On June 5, my father joined several hundred troops from the Royal Winnipeg Rifles aboard a requisitioned Irish ferry where he was teamed with Charles Lynch, a young Canadian reporter working for Reuters. There was an old piano aboard, which Lynch was able to play as they crossed the Channel. Both men would later recall the poignant scene as young soldiers, many of them anxious and fearful, broke the tension by singing Vera Lynn and Maurice Chevalier songs as they approached the certain horror of Juno Beach.

Charles Lynch, reporting for Reuters (LAC)

The two correspondents transferred to an infantry landing craft for the final stretch to the beach at Graye-sur-Mer. At about 30 metres from the shore – weighed down by their typewriters, steel helmets and gas masks – they faced the challenge of jumping into choppy water at least waist-high. German machine guns had been taken out in the first assault wave three hours earlier but there was still shelling when they got ashore, and the chilling sight of dead Canadians lying on the beach.

My father would soon learn the bad news that Army PR wouldn’t be able to get recording equipment to the beachhead for several days. His only option was to write a 2,000-word account of the landing and ship it to England to be read by someone else and recorded for the CBC. Sitting down at the kitchen table of a local couple who had graciously welcomed him and Lynch into their home, he typed a moving description of everything he’d seen since the landing.

“I have been though many battles,” he began, “but I was never as excited as when my time came to go ashore, for this was France and the beginning of the end.” As in the dispatches of some of his colleagues, my father wrote of the courage of young Canadian soldiers, many of them new to battle, advancing resolutely against the Germans and achieving their planned objectives for the first twenty-four hours of D-Day.

“I was with the Canadians,” my father reported, once he was able to broadcast, “and I say the Canadians had everything: wonderful skill as well as wonderful dash.” Eighty-six percent of the Canadians back home listened to his wartime radio reports.

Listen here: ‘Witness to D-Day’, Matthew Halton’s CBC Radio Broadcast

He also marvelled at the warmth of the welcome by the French people who greeted them, despite the fact that some of their homes had been badly damaged by heavy Allied bombing on previous days. He reported the “wild, weeping, lovely welcome” in his radio broadcast. He wrote of a local woman he saw putting a rose on the face of a dead Canadian, and of Normans plying Canadian soldiers with Calvados, the raw Norman apple or pear brandy. But my father and Lynch perhaps benefited more than most from local hospitality. The farmer and his wife who had allowed them to work in their kitchen also let them stay overnight in their home. While their fellow correspondents were sleeping in the rough, Lynch would later recall, “Matt and I were the only two men sleeping in featherbeds on D-Day.”

That was small comfort for the painful discovery my father was soon to make. His long report on the assault had reached England but somehow got lost in the British government’s censorship bureaucracy. “The hair-brained bastards!” he wrote to my mother. “You risk your life covering the greatest story in history… and then it is lost in the Ministry of Information.” And still with no recording equipment available, he had to wait another two days to get a pass to return to England and make his first broadcast on the assault for CBC.

It took even longer for Marcel Ouimet, his gifted Radio-Canada colleague, to make his first broadcast from Normandy. In an angry message to his to his unit manager in London, Ouimet complained bitterly that he had missed making the most important broadcast of his life. “It’s like being a photographer without a camera,” he said. It would be four days before BBC recording equipment was made available for Canadian correspondents and a full two weeks before a CBC recording van was brought over to France.

Lynch, filing for Reuters, faced frustrations of a different kind. Army PR had brought over baskets of carrier pigeons, hoping they could be used to send out the first press bulletins to England before regular communications could be set up. Lynch dutifully placed his copy in a small capsule that was attached to a pigeon. To his dismay, the bird flew off in the direction of the German lines instead of its home loft in Southampton.

Lynch tried again with several other so-called “homing” pigeons, only to see them fly off in the same wrong direction, their GPS navigation apparently rendered inoperative by hormones because it was their mating season. Furious, Lynch shook his fist at the departing birds with a roar that became part of journalistic legend: “Traitors! Damned traitors!” The quote would later appear in the best-selling book, and its movie version, The Longest Day, though Lynch complained in his memoir that his Canadian identity was obscured by the actor’s British accent.

CP correspondents Ross Munro (left) and Bill Stewart (centre) with Montreal Gazette correspondent Lionel Shapiro (right) in La Villeneuve, France, on August 13, 1944 (LAC)

CP correspondents Ross Munro (left) and Bill Stewart (centre) with Montreal Gazette correspondent Lionel Shapiro (right) in La Villeneuve, France, on August 13, 1944 (LAC)

The early failures of some of the war correspondents underscored the success of others. Most prominent was the lucky break that enabled Ross Munro of CP to score one of the biggest scoops of the war. Munro had crossed the Channel on a British destroyer. Before transferring to a landing craft he learned that the ship would return to England in a few hours to pick up Gen. Bernard “Monty” Montgomery and bring him to France. That delay gave Munro enough time to write a long dispatch chronicling the dramatic scenes of the landing and then have Army PR get the copy back on the destroyer before its departure to England. The next day, Munro’s story – the first datelined from Normandy – was on the front page of hundreds of newspapers in the English-speaking world: CANADIAN INVASION FORCES WIN BEACHHEAD AND MOVE INLAND.

The first film and photos of the invasion were also the work of Canadians. Bill Grant of the Canadian Army Film Unit shot the now-classic footage of soldiers from New Brunswick’s North Shore Regiment jumping from their landing craft before storming the shore. It was used in newsreels in cinemas all over Britain and North America. An army still photographer, Frank Dubervill, chalked up another scoop by shooting the first pictures of the assault from onshore.

In retrospect, there was an awestruck, celebratory quality about the reporting of D-Day by the Canadian correspondents. That was partly because the Manichaean quality of the conflict was so stark and the stakes for humanity were so high, that any pretense of journalistic equivalence would have been absurd. More immediately, after five years of Hitler’s rampage across Europe, the biggest military operation in history had succeeded brilliantly for the Allies, with many fewer casualties than predicted.

Munro wrote that, “You felt an immense pride in your country to see what they achieved on the Norman coast. Ouimet described young soldiers “going into battle as if they were veterans, confident in their superiority.” My father spoke of “immortal hours” endured by “our superb assault troops.” After the war, there was some acknowledgement that the correspondents were cheerleaders for the Allied cause, but no apologies. “You believed the cause was right,” said Munro. “Hitler had to be put down or your world wasn’t going to exist.”

David Halton served as a senior correspondent for the CBC, including in Washington, London, Paris and Moscow. He is the author of Dispatches from the Front: The Life of Matthew Halton, Canada’s Voice at War.