The UK Election So Far: The Stakes, the Players, and, of Course, Nigel Farage

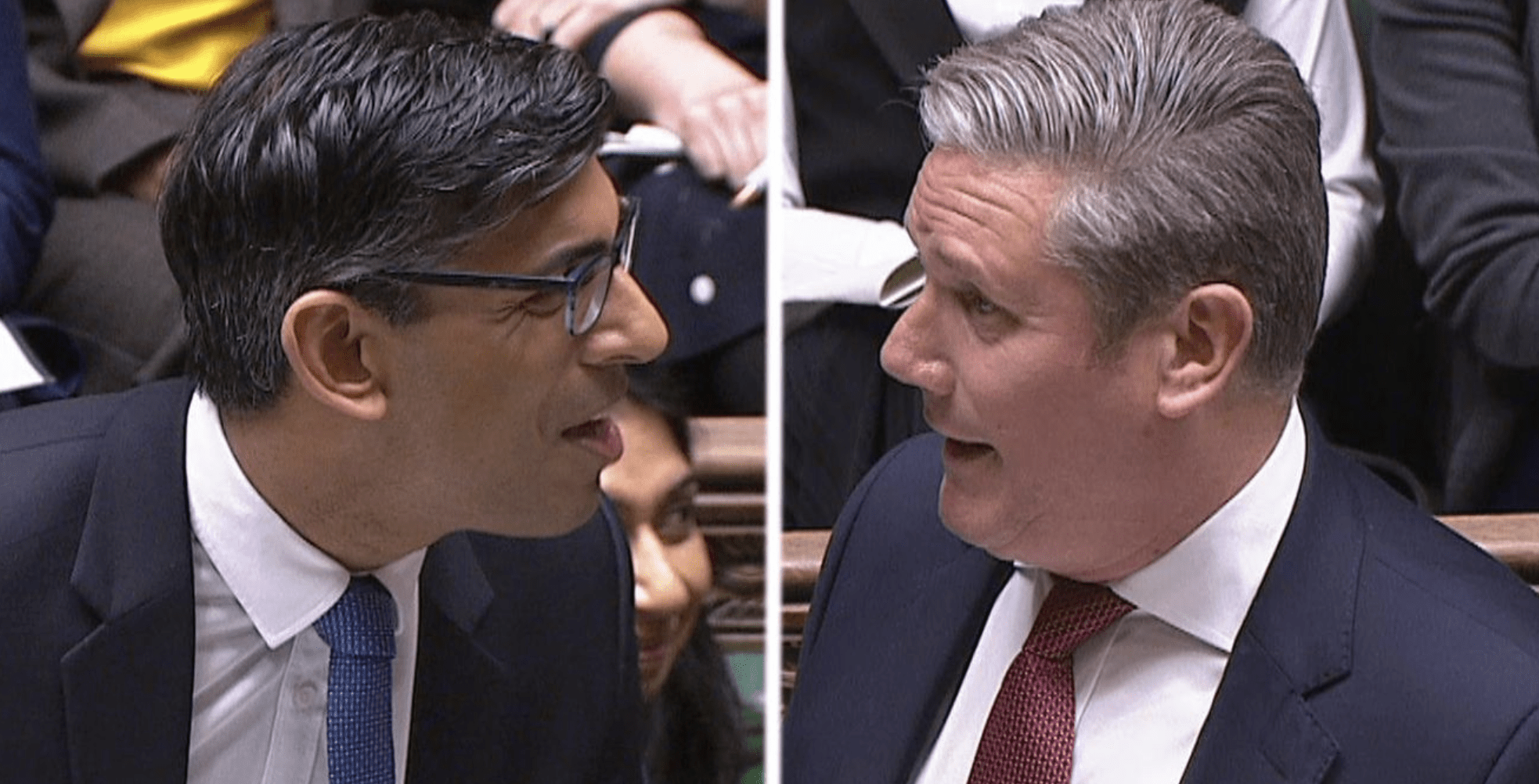

Conservative Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and Labour Leader Keir Starmer/Sky News

Conservative Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and Labour Leader Keir Starmer/Sky News

By Ben Collins

May 30, 2024

On May 22, British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak stood outside 10 Downing Street in a downpour — gamely tempting Fleet Street headline wags to reference his failure to come in out of the rain — and called a general election for Thursday, July 4.

This announcement took a lot of people, including, it appears, Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt, by surprise. The Conservatives started the campaign with various opinion polls showing them around twenty points behind the opposition Labour Party — the spread deemed by conventional political wisdom on both sides of the Atlantic to define insurmountability. Since then, this week’s Sky/YouGov Great Britain poll has the Conservatives 27 points behind.

After fourteen years of Conservative government consisting of five different prime ministers, all the evidence points to this being a change election. Labour, led by former human rights barrister Sir Keir Starmer, are on course to become the party of government, with a large majority. The Conservative party will likely lose votes because of the upstart, right-wing Reform party, founded by garrulous Brexiteer Nigel Farage, now led by real estate magnate Richard Tice. But at this writing, Reform are not expected to get more than one or two seats. There is an outside chance that with tactical voting in a first-past-the-post system, the Conservatives could be replaced as the second-largest party in terms of number of seats, by the Liberal Democrats, led by career politician Ed Davey.

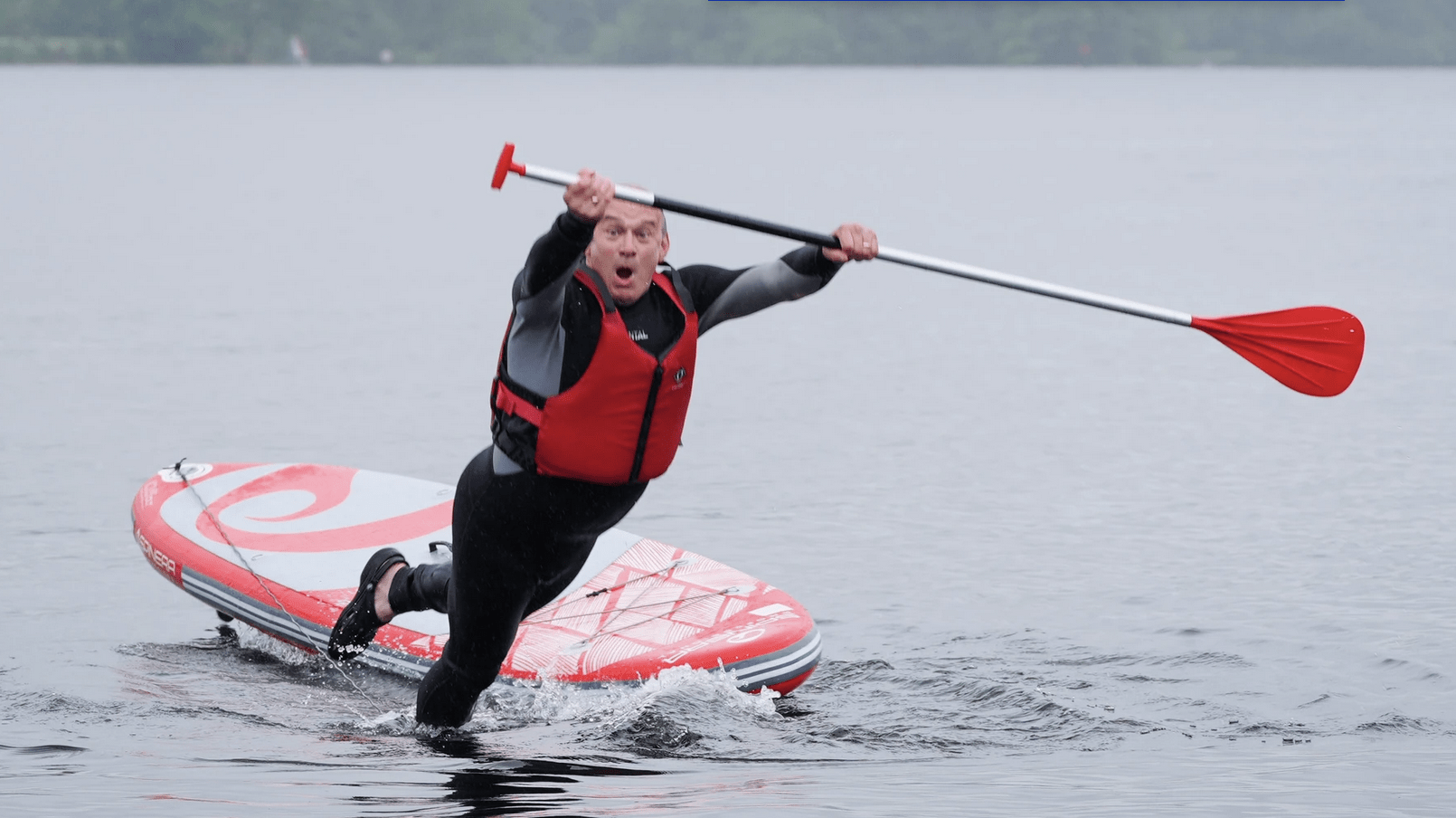

After one week, the campaign highlights so far are a proposal for national service from Sunak, a backbencher/free speech derailment for Starmer, and Davey’s inexplicable photo-op repeatedly falling off a paddleboard. On Tuesday, Farage returned to the fray, more theatrically than electorally.

This UK election is likely to be a watershed event for regional nationalist parties, i.e. those who want independence from Britain, notably the Scottish National Party (SNP), which has governed Scotland since 2007. While they strongly opposed Brexit, as did the majority of voters in Scotland, the SNP have suffered from various scandals in recent years. The Labour party is resurgent in Scotland, as in the rest of Britain, and this could result in the SNP seats at Westminster being reduced significantly. And a new Labour government at Westminster would be unlikely to allow the SNP to hold a second independence referendum during its first term. Arguably, this could be a better outcome for the SNP, rather than suffering a second referendum defeat as the Quebec Sovereignty movement did in 1995.

In Wales, despite Labour being the party of government in the Senedd (Welsh Parliament) since it was established in 1999, the pro-Welsh independence party, Plaid Cymru, does not appear to be in a position to make gains.

Lib Dem Leader Ed Davey’s fourth (fifth?) consecutive dismount from a paddleboard, hands-down besting Boris Johnson’s zipline freeze for ‘action man’ political photo-op debacles /PA

Lib Dem Leader Ed Davey’s fourth (fifth?) consecutive dismount from a paddleboard, hands-down besting Boris Johnson’s zipline freeze for ‘action man’ political photo-op debacles /PA

If indeed Labour forms the next UK Government, it will inherit multiple crises on Day One: A war in Ukraine, the ongoing bloodshed in Gaza, the climate crisis, a shortage of housing, a health care system at breaking point, a sluggish economy and huge levels of government debt leaving very little fiscal flexibility. Starmer will want to rebuild relations with the European Union (EU), although he has stated he won’t seek to undo Brexit. There will be little capacity to deal with constitutional tensions across Britain. If the Labour party secures the majority of votes and seats in England, Wales and Scotland, those results will be used as a justification to refuse all demands for votes on Scottish or Welsh independence.

Northern Ireland, however, is in many ways a place apart. Unique within the UK for its lack of contiguity with Britain and for sharing a land border with an EU country, it has trading arrangements with the EU which are different to the rest of the UK. It is also the only part of the U.K. where the Conservatives, Labour and Liberal Democrats do not stand for election across all constituencies. Scotland has no legal route to an independence referendum unless the U.K. expressly allows one, but Northern Ireland has an explicit right to a referendum on Irish unity, as set out in the Good Friday Agreement (as I recently wrote about for Policy). If Northern Ireland were to leave the UK and reunify with the rest of Ireland, it would automatically become part of the EU. This would make post-Brexit arrangements for both Britain and the island of Ireland more straightforward. It would not create an existential crisis for the UK, whereas Scotland or Wales leaving the UK would cause a constitutional reckoning.

At the time of the last Westminster election in 2019, more pro-United Ireland MPs were elected from the region than pro-British ones. Since then, Sinn Féin, the largest pro-United Ireland party has become the largest party in local government and in the Northern Ireland Assembly. The fact that there is now a Sinn Féin first minister, Michelle O’Neill, in a region created specifically in 1921 to have a permanent pro-British majority, is itself seismic. These elections could be the first Westminster election where there are more pro-United Ireland votes than pro-British ones in Northern Ireland, which would make a border poll on Irish unity more likely.

In 2019, Boris Johnson’s Conservative sweep was seen as a mandate to “get Brexit done” — a result of significant consequence for Britain’s relations with the EU and its own economy. As with all UK elections, this one, too, will be about more than who gets to occupy the lectern outside Number 10, rain or shine.

Ben Collins is a Belfast-based communications consultant and author of the book Irish Unity: Time to Prepare.