Canada Among Nations: In Search of Democratic Revival

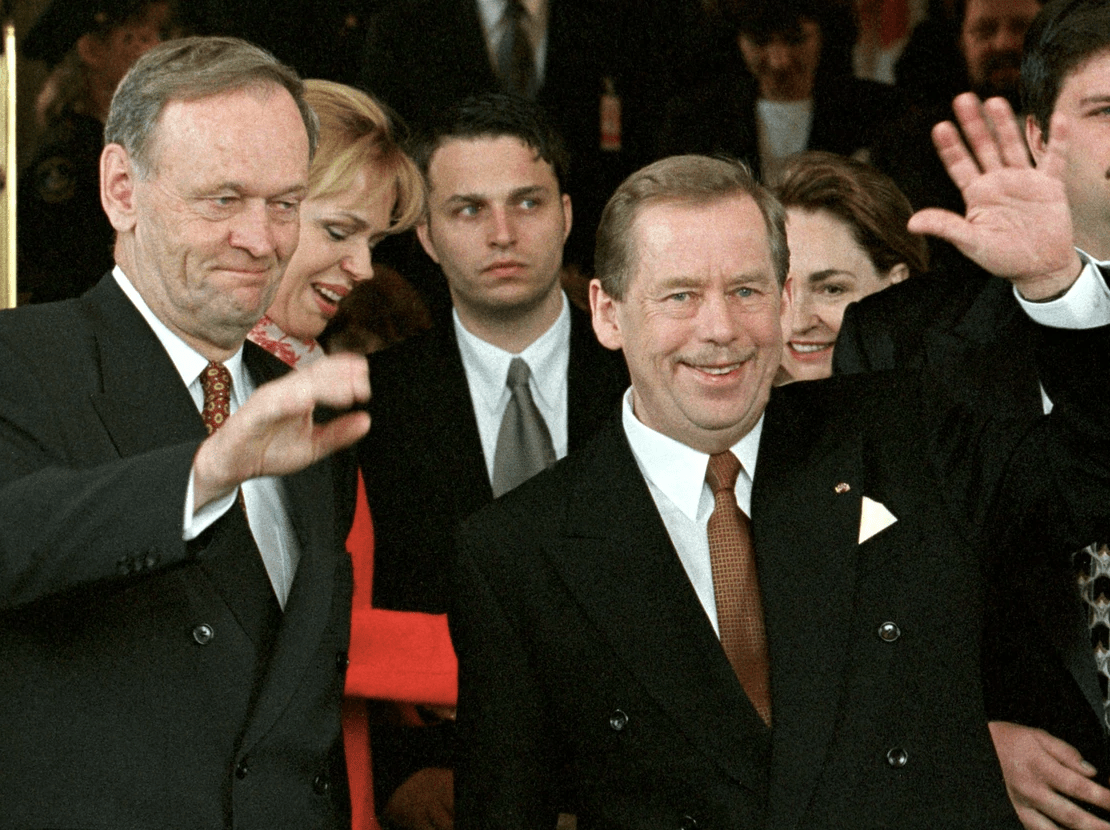

Prime Minister Jean Chrétien and Czech President Václav Havel in 1999/Reuters

Prime Minister Jean Chrétien and Czech President Václav Havel in 1999/Reuters

The following is an abridged version of the chapter contributed by former Canadian ambassador to Russia, to the European Union, to Italy and high commissioner to the United Kingdom, Policy Contributing Writer Jeremy Kinsman, to Democracy and Foreign Policy in an Era of Uncertainty, the latest Canada Among Nations international relations anthology, published by Palgrave Macmillan (2023).

By Jeremy Kinsman

May 29, 2024

At a time of disruptive change and multiple challenges, almost all established democracies remain stressed by pressure from home-grown, identity-based, nationalist populism that often scapegoats minorities. It is fuelled by social media that channel disinformation and distrust of government, as well as of science.

The preoccupations of established, inclusive democracies tend to be inward-looking. The effect is to demote democracy support for others down the list of priorities. The impression this conveys of gradual withdrawal of official interest and solidarity has been disconsoling and demoralizing to human rights defenders and civil society proponents in repressive non-democracies.

Democratic recession mostly occurs by stealth. Once majoritarian populists win power by exploiting anxiety, they exploit that majoritarian support to eliminate the effectiveness of democratic and human rights safeguards in courts, tribunals, and legislatures, backsliding incrementally on civil liberties, inclusivity, and openness, consistently subtracting from tenuously established democratic space, thereby polarizing opinion, often against minorities as well as against outsiders.

Nationalism continues its ascent at the expense of globalism and multilateral cooperation. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine exemplifies Putin’s expansive nationalism and challenges bedrock international norms against aggression. V-Dem’s “State of the World” summarizes it thus: “A war began in Europe…the doing of the same leader who triggered the third wave of autocratization when he began to derail democracy in Russia 20 years ago. The invasion seems like a definite confirmation of the dangers the world faces as a consequence of autocratization around the world.”

Some argue that this confirmed trend means that democratic allies should face up to the reality that major autocracies, particularly China and Russia, are immutably hostile, and to concert in oppositional recognition that the world is again divided.

Democratic concertation can better support coordinated positive policies in defence of democracy. However, creating a closed democratic circle to confront what is seen to be an outside threat is a leap to the wrong conclusion. Most countries are “in-between” democracy and autocracy.

Multiple meetings of Canadian, German, and other scholars and experts over the course of 2021-22 under the Canada-Germany civil society project “Renewing Our Democratic Alliance” (RODA) advised that the “silent majority” of the world’s nations, especially the poorest countries that are most vulnerable to exogenous adversities in global trends, do not want to be coerced into one side or the other in a renewed cold war. That reticence clearly emerged at recent meetings of the G-20, ASEAN, APEC, La Francophonie, and other multilateral groupings.

Globally, we are at an inflection point when the existential nature of transnational challenges of health and climate and other inter-connected ongoing crises underlines the reality of universal interdependence. The necessity of an effective international response requires protecting the potential for cooperation on vital challenges to the global commons, as recognized by Presidents Joe Biden and Xi Jinping at their recent Summit in Bali, Indonesia.

Democracies are committed to protecting the rules-based order by supporting Ukraine’s defence of its national sovereignty “for as long as it takes.” But they should simultaneously encourage the global community to mobilize for its common agenda of necessity. At home, they need to reinforce their own institutions, intensify links with trusted partners, and provide exemplary inclusive and effective governance. And our democratic societies should re-boot concern for the eroding positions of human rights defenders and others seeking open government elsewhere.

Citizens everywhere share expectations: for stability, security, and well-being, but also for fairness and transparency, opportunity, and the impartial rule of equitable law. Democracies should renew confident support for this quest that has continued wherever humans live – for human rights, dignity, and accountability. To succeed in supporting others, democracies need to know much better what is needed, what is feasible, and what works best.

Disappointment in Washington, 2014

What remained of 1989’s confidence that democratization would be the prevailing global outcome was decisively depleted by the Arab Spring’s burnout in the early 2010s. Brutally repressed in Syria, it subsided in disarray elsewhere, especially Egypt, where democratic reformers couldn’t unite sufficiently to sustain public confidence that they would deliver stable governance.

By 2014, President Barack Obama confided private advice that NGO advocates of support for democracy development should first figure out what succeeds. His impression was that we had got it muddled.

At the Washington-based but internationally inclusive Council for a Community of Democracies (I had been since 2007 inaugural director of its program of democracy development support), we experienced first-hand the waning of donor backing in the wake of similarly disenchanted questions as President Obama’s.

Human rights defenders and political activists in increasingly self-confident autocracies abroad felt orphaned by this apparent weakening of concrete soldarity as authoritarian illiberal regimes cracked down on their rights, tendencies which have deepened since, especially in China and Russia.

Today, when public opinion in established democracies was becoming increasingly preoccupied by polarization at home, 71% of American voters believe their own democracy is at risk. (New York Times/Siena College poll). But only 7% identify that as “the most important problem in the country,” in comparison to the worst inflation since 1982, the withdrawal of federal abortion rights after 50 years, and an uncertain perception of surging crime.

While foreign policy and budgetary agendas of established democracies have now re-geared to meet the need to help Ukraine protect its sovereignty, managing this support and its considerable costs to treasuries has further narrowed the bandwidth available for support of democracy development elsewhere, and for lightening the impact of the world’s systemic “polycrisis” on poorer countries.

Citizens of democratic countries need to relate more effectively to the needs of other countries. Then, to provide practical support for democratic development, they need first to understand better its process and its sustaining features – why it succeeds and why it fails.

The building blocks of democratic behaviour and competence are essentially:

1) the consolidation and protection of civil liberties, that are foundational to openness and inclusion, and which

2) allow civil society, which is the incubator of democratic behaviour, to develop and flourish.

President Václav Havel’s advice

It is axiomatic that elected governments retain public support for their execution of governance and delivery. But it is where neophyte democratic regimes often fall short.

Democracy needs to be an all-of-society effort. The human factor is paramount. Successful inclusive democracy relies as much on human behaviour as it does on process and institutions.

It needs the anchor of acknowledged rule of law. To proceed with transformation to freedom without the rule of law, as Russia did in the early 1990s, is to invite chaos. But the rule of law depends on more than establishing courts and statutes. As Carnegie legal scholar Thomas Carrothers has argued, “it’s what’s in citizens’ heads that matters.”

Václav Havel, whose trajectory from dissident advocate of freedom to President of Czechoslovakia he later summarized as a journey “from the prison cell straight into the presidential palace” (Preface, A Diplomat’s Handbook for Democracy Development), understood this imperative, but also its difficulty.

Thanks to my wife Hana, a political refugee to Canada from Prague, I met Havel shortly after Civic Forum’s Velvet Revolution had displaced in November 1989 what had been viewed as the most hardline communist regime in Europe. To Hana’s question, “What is the first thing you think of on waking up in Prague Castle?” The ex-playwright sighed, “Oh, God, I’m the President.”

His enduring worry was whether people could learn to “be nicer” to each other, because democracy relies on civic cooperation. To Hana’s remonstration that he could inspire positive civic behaviour, because the people loved him, he riposted “Sure, they love me now! Wait till they find out we don’t know what we’re doing.” Havel’s friend and spokesman Ambassador Michael Zantovsky recalls – in his biography, Havel – the President warned his team, “We are coming in as heroes, but in the end, when they realize what a mess we’re in and how little we can do about it, they will railroad us, tarred and feathered, out of town.” Having realized that “the velvet was wearing thin”, Havel anticipated “the hunt for villains, scapegoats and culprits would start soon.”

It often did, once people who had celebrated 1989’s recovery of freedoms in expectation that democracy was synonymous with prosperity, began to realize that, as Fareed Zakaria wrote, “democracy is a long, hard, slog.”

Havel’s was one of several untried democratic governments facing enormous challenges of repairing and transforming societies broken by generations of totalitarian rule. Anna Porter reported in The Ghosts of Europe that Polish reformers Kiron, Geremek, and Michnik “confessed” to post-Soviet economic “shock therapy” proponent Jeffrey Sachs “that when they came into power they would not be able to make enough of a difference in the desperation of people’s lives…that they would be held responsible for the crisis.”

When President Havel visited Moscow in 1995, he asked how I estimated the Russian democratic experiment’s progress. To my fairly optimistic report, he replied sardonically, “Sixty years. Sixty.”

After Havel’s death in 2011, Michael Zantovsky clarified the source of that cryptic response. In 1990, Havel read an essay by Ralf Dahrendorf which predicted that a democratic transition could design a new political order in six months, but that it would take six years to change the legal system, economy, and institutions – and 60 years to change the people’s ways of thinking.

It is the people who make democracy work through their civic behaviour. It is civil society that enables them to learn how.

Civil Society

Civil society – what citizens do together in shared endeavours, often non-political – forms the building blocks of democratic self-realization. It enables citizens to learn from and work with each other toward shared policy and delivery outcomes, developing the necessary habit of achieving consensus in self-governance.

In apartheid-era South Africa, the Black population was denied the opportunity to organize in civil society, with the exception of churches and football clubs that became, in time, self-governing incubators of political solidarity whose political face was the African National Congress (ANC), the clandestine party of opposition that ultimately prevailed in the historic struggle.

Hardline autocracies suppressed civil society’s development, especially in the communist bloc. In Poland, Solidarity became in 1980 the first mass movement outside state or party control. It gave the subsequent transition to democracy a head start. In Tunisia, an active women’s movement, unions, and professional societies that had existed for decades provided in 2010 the social capital to enable the revolution that ignited the Arab Spring (though buoyant popular expectations were to be disappointed by the daunting economic challenges that remained).

Human rights are paramount

Since 1989, much has been grasped about best practices for transit to democracy, notably that each national trajectory is different. There is no single systemic model or organizational template for a successful democratic transition. But the availability of universal human rights remains an essential precondition.

It was a longstanding French belief that the perception of US-led democracy promotion had become conflated into being a surrogate for US-led influence and economic doctrine. Democracy promotion was as apt to divide countries as to bring them together, being seen by many non-democracies as an unacceptable intrusion on national sovereignty.

But by contrast, human rights are, in principle, litigatable internationally. Almost all countries are signatories of the relevant foundation covenants of the United Nations and other international bodies.

The differentiation is not one of prioritization, because democracy and human rights are integrally linked. Without human rights, civil society has little chance to breathe. Without the breath of civil society, democracy has little opportunity to grow.

Human rights are therefore basic to democratic evolution. If they are present, inclusive democracy development has a way to gain traction, provided that democratic aspirants, once in office, are able to deliver effective government to the electorate.

The question is how democracies can best contribute. Democracies should begin by holding all countries – beginning with themselves – to their commitments to international human rights covenants. Democracies have the leverage of favour and influence. Foreign relations form concentric circles. Inner circles of close relationships with corresponding benefits will necessarily be reserved for trusted partners. Evidence of human rights abuse should inevitably affect the quality and intensity of bilateral relationships. This principle must be consistently applied,irrespective of country-specific transactional, commercial, and geopolitical interests.

How can democracies best support democracy development?

Can democratic diplomacy and political engagement be viewed in new ways to enable better partnering to support democratic development?

1. We need new tools for democracy support:

Old donor country-recipient country development models don’t apply. A spirit of mutual learning is essential. Initially, programs to assist post-Cold War transitions in ex-Iron Curtain countries assumed a symmetry of intention, and placed the focus on institutional mentoring, and election mechanics. That approach produced mixed results.

In this century, we need to choose the most effective vehicles for the transfer of capacity. Democracy development assistance needs to be re-geared and de-bureaucratized.

The most helpful route is via civil society. The country-case studies in A Diplomat’s Handbook reveal that “the best vehicles for outside support (for civil society actors) are rarely government programs, however well-intentioned. They are not good at it. Outside support for democratic capacity-building potential comes best from international civil society partnerships, with the lead partner being the one inside the country.”

The partnership support budgets of democracies should show as much support for civil society as possible. There are calls to apportion 25-30% of development support funds to civil society to administer directly. Juxtaposing beneficial connective tissue via direct civil society-to-civil society links, often for functional non-political and local civil society projects needs to be enhanced.

2. Democracies should share assessments and agree on basic principles:

Can democratic countries cohere basic principles of concept and operation?

Conceptually, without proposing that there is a single theory of transitional success, Western democracies should acknowledge basic normative assumptions about conditions needed for democratization, such as:

– democracy cannot be exported.

– democracy needs to emerge authentically from within the country in question.

– there is no single theory or preferred template, but respect for civil liberties and human rights, gender equity, and an open environment for media commentary and reporting are foundational.

– inclusivity is essential – unless citizens enjoy equal rights, the country’s status is not democratic.

– fairness and respect for human dignity are paramount; corruption corrodes conclusively.

– democracy’s building blocks are bottom-up, lodged in civil society, where participants experience agency and the essential facility of compromise.

– civic behaviour needs time to become second nature to citizens, though some societies (e.g., Taiwan, and the Republic of Korea) show a faster track.

– each trajectory is different and outcomes vary, including truth and reconciliation efforts linked to respectful pacting between old and new orders.

Operationally, Working together with civil society partners, democracies should:

– share needs analyses, audits, best practices, to enable comparisons of benefit;

– divide labour, and leverage national contributions to maximize comparative advantage, often cooperating on country-specific projects.

3. Multilateralism

Democracies are generally, by disposition, multilateralists. They help build democratic capacity and norms into multilateral functional organizations that radiate those outward.

They should:

– ensure that the democratic value standards of multilateral “clubs” – the EU, NATO, OECD, Council of Europe/ECtHR, the Commonwealth, La Francophonie, OAS, etc. – are actually applied;

– use sanctions selectively and judiciously to encourage correct international behaviour only after considering the alternative of positive incentives (as in the JCPOA with Iran);

– cooperate via diplomatic missions, which should maintain local encouragement for civil society and support of independent media if possible, and demarche collectively incidents of unaddressed human rights abuse.

4. Other actors, policy imperatives, and positive messaging:

International business investments can play an important role in channeling inclusive and equitable governance. If corporate practice of outside investors consciously aligns local activity with governance norms increasingly obligatory in industrialized democracies, it can embed in the local workplace ethics such as transparency, accountability, meritocracy, sustainability, and gender equity that can transfer to civil society.

Democratic countries (indeed all countries) should prosecute vigourously evidence of corrupt practices abroad and end the competition to offer profitable havens to oligarchic and criminal wealth.

Arms sales to dictatorships and repressive regimes are a toxic insult to the professed beliefs and credibility of democratic countries.

The fake news phenomenon

Whatever democratic governments do to support democracy development and human rights would be semi-futile without parallel attention to the internet’s contribution to polarization and illiberalism. Clearly, the early notion the internet would bring people together and enable sharing of evidence-based information has been overtaken by the pernicious phenomena of a) fabrication and dissemination of alternate realities through ubiquitous and unregulated social media, and b) suppression of free media and commentary.

Social media platforms themselves do not threaten democracy, but their business models have harmful collateral effects. As Dr. Ulrike Klinger, Professor of Political Theory and Digital Democracy at the European New School of Digital Studies said in a “paper presented to the RODA conference in Montreal in Sept. 2022: “They did not invent disinformation, hate speech, radicalization or propaganda, but they make it worse. Their business models and the design of their largely intransparent and non-accountable algorithmic systems reward and fuel negativity, hate and anger, reinforcing the overblown impact of aggressive, abusive hyperactive users and groups… Their lack of transparency and accountability are fundamental obstacles to the functioning of democratic public spheres.”

Dr. Klinger urges the EU and countries such as Germany and Canada to provide leadership in platform regulation by shoring up human agency as the driving factor – to take control, via form legislative initiatives.

Freedom of the press

To defend freedom of the press, without which democracy cannot flourish, and to diminish the destructive effect of disinformation and propaganda, Antoine Bernard, Research Director of Reporters Without Borders (RSF), urges support for the Forum on Information and Democracy that was created by RSF and 10 civil society organizations to propose regulatory frameworks and public policies. At the United Nations General Assembly in 2021, the Forum announced the formation of a coalition of democracies to enable the safeguarding of a “democratic information space” via an International Observatory on Information and Democracy.

To counter the blocking in Russia of trustworthy news producers, RSF initiated “Collateral Freedom”, which enables continued access to censored websites, such as Meduza, Deutsche Welle, Radio France International and France 24 TV.

Canada should be a leader in advancing the above precepts and initiatives among democratic nations, as set out in the RODA project to create a Democracy Solidarity Network.

Recommendation for a solidarity network

The Renewing Our Democratic Alliance project (RODA) between Canadian and German civil society actors concluded in 2022 two years of consultation by urging pro-democracy actors to establish a new likeminded group of governments and international civil society to concert to protect democracy, defend human rights, and strengthen international cooperation to enable effective outcomes on the inter-connected challenges facing humanity today. A Network for Democratic Solidarity will aim to strengthen and protect global commitment to universally acknowledged civil liberties and human rights, and will concert against the systemic export of malicious disinformation.

The Network would also provide a channel for participating states and civil society organizations to coordinate policy responses on inter-linked multilateral issues, to build traction for effective decision-making in international fora that are polarized. The group will aim to ensure the sort of overall oversight of a system that is currently siloed by often competing negotiating solitudes, sector by sector.

The new like-minded group would begin with a core of inclusive and globalist democracies, plus international civil society, from the South and North, and operate in the spirit of mutual learning in a pluralistic world. The group will start from the perception that constant vigilance in the quality of their own democracy is essential to the credibility of efforts to support democracy elsewhere.

Democratic publics need to pay more attention to the lives of others

An eternal debate in the conduct of foreign policy is how to calibrate the right mix of “values” and interests. Canada’s internationalist vocation and the view that human rights are indivisible make the “lives of others” an enduring preoccupation of Canadian globalist policy, in keeping with democratic values and other principles that guide our Charter of Rights and Freedoms. They are not an ideological end in themselves but constitute “a form of government relying on the consent of the governed… a means of fulfilling individual lives and pursuing common purposes.” (A Diplomat’s Handbook for Democracy Development Support).

In 1989, Václav Havel wrote to the PEN International Congress in Montreal (which he was not permitted by Czechoslovak authorities to attend in person) of the “venerable practice of international solidarity.”

“In today’s world, more and more people are aware of the indivisibility of human fate on this planet, that the problems of any one of us, or whatever country we come from – be it the smallest and most forgotten – are the problems of us all; that our freedom is indivisible as well, and that we all believe in the same basic values, while sharing common fears about the threats that are hanging over humanity today.”

It rings as true now as it did then.

Contributing Writer Jeremy Kinsman served as Canada’s Ambassador to Russia, Italy and the European Union and as High Commissioner to the UK. He is a Distinguished Fellow of the Canadian International Council.