A Belated Farewell: L. Ian MacDonald on Brian Mulroney

Brian Mulroney and L. Ian MacDonald in April, 2022/Gray MacDonald

Brian Mulroney and L. Ian MacDonald in April, 2022/Gray MacDonald

As many of our readers know, Policy Publisher Emeritus L. Ian MacDonald, who served as Prime Minister Brian Mulroney’s chief speechwriter and wrote the bestselling biography Mulroney: The Making of the Prime Minister, has been on hiatus since June 2023 due to a cognitive impairment. This lightly edited piece reflects a new level of lucidity in Ian’s writing thanks to a combination of time and treatment.

By L. Ian MacDonald

May 19, 2024

When Brian Mulroney’s funeral was held in Montreal on March 23, I was unable to perform my duties as an honorary pallbearer. After a year of health challenges, I watched the national farewell from a hospital room nearby.

In the weeks since, I’ve been asked what it was like to work for him as his principal speechwriter.

It was a privilege and a pleasure.

Writing for him was like riding the great Secretariat in the Belmont Stakes, in which he clinched the Triple Crown of thoroughbred racing in 1973.

You just let him run and win by 31 lengths.

We met half a century ago in 1972 at the Carrefour des Canadiens bar in the shopping mall of Place Ville Marie in Montreal, downstairs from his law office at Ogilvy Renault.

It was a Friday-at-5 chance encounter that led to a cherished friendship.

He was working the room that day, peddling a poll of party choice in the upcoming federal election. The Tories had hired Bob Teeter, a top Republican pollster south of the border, who found the Conservatives virtually tied with the governing Liberals.

It was hard to believe that Progressive Conservative leader Bob Stanfield could be competitive with Pierre Trudeau. After all, this was Montreal, a different place from the Rest of Canada.

It turned out that Teeter was right. The Tories very nearly won the election, losing by only two seats, 109 to 107.

For Mulroney, the 1972 election marked the beginning of his rise to prominence in the Tory rank and file.

One thing about him, then as later – he was authentic and transparent.

When he stopped drinking in the late 1970s, he never spoke about it, but his friends knew. When he stopped smoking when he was opposition leader in 1983, MPs and staffers noticed he no longer lit up in the members’ lounge before question period.

As his longtime executive secretary Ginette Pilotte told him: “First you quit drinking, then you quit smoking. Next, you’ll quit swearing, and that’s when I’ll quit.”

One thing he couldn’t quit—he had vertigo, which was why the advance teams made sure the podium was always on the floor rather than raised.

He also had a sense of humour that would surprise a lot of people.

When he hired Toronto Star journalist Bill Fox to be his press secretary, he pitched the deal with a one-liner on the phone.

“I’m going to Rome to see the Pope,” he said. “You want to come?”

He campaigned at the United Nations and in the Commonwealth for the release of the imprisoned Nelson Mandela.

When Mandela was released, he called Mulroney to thank him and say he would like to make his first speech in Canada.

“Do you want me to send a plane for you today or tomorrow?” Mulroney asked.

Canada was also the first country to recognize the independence of Ukraine in December 1991, against the advice of the first George Bush and Mikhail Gorbachev. (At Bush’s funeral in Washington in 2018, Mulroney and Gorbachev sat together behind the Bush family).

As Mulroney explained to them: “We have 1.2 million Ukrainian Canadians,” he said, including the governor-general, Ray Hnatyshyn, whom he had appointed.

This was in early December 1991, only three weeks before the collapse of the Soviet Union itself.

In editing drafts of speeches, he always cut to the chase. His handwritten notes with a black felt pen invariably improved the final product.

He had a way with people, as did Mila, who for nine years hosted events at 24 Sussex with unfailing elegance and grace. No matter how hard his days in question period, managing the federation and Canada’s place in the world, he was always happy to head home.

People around him always knew Mila and the kids came first. On the day he won the Conservative leadership in Ottawa in June 1983, he cut short an interview with CBC’s Peter Mansbridge with the polite explanation that he had to get back to the Château Laurier for Caroline’s ninth birthday party.

At work, he always had a good word for staff in the PM’s office.

“You knew he cared about everyone around him,” says Lee Richardson, a former deputy chief of staff in the Mulroney PMO.

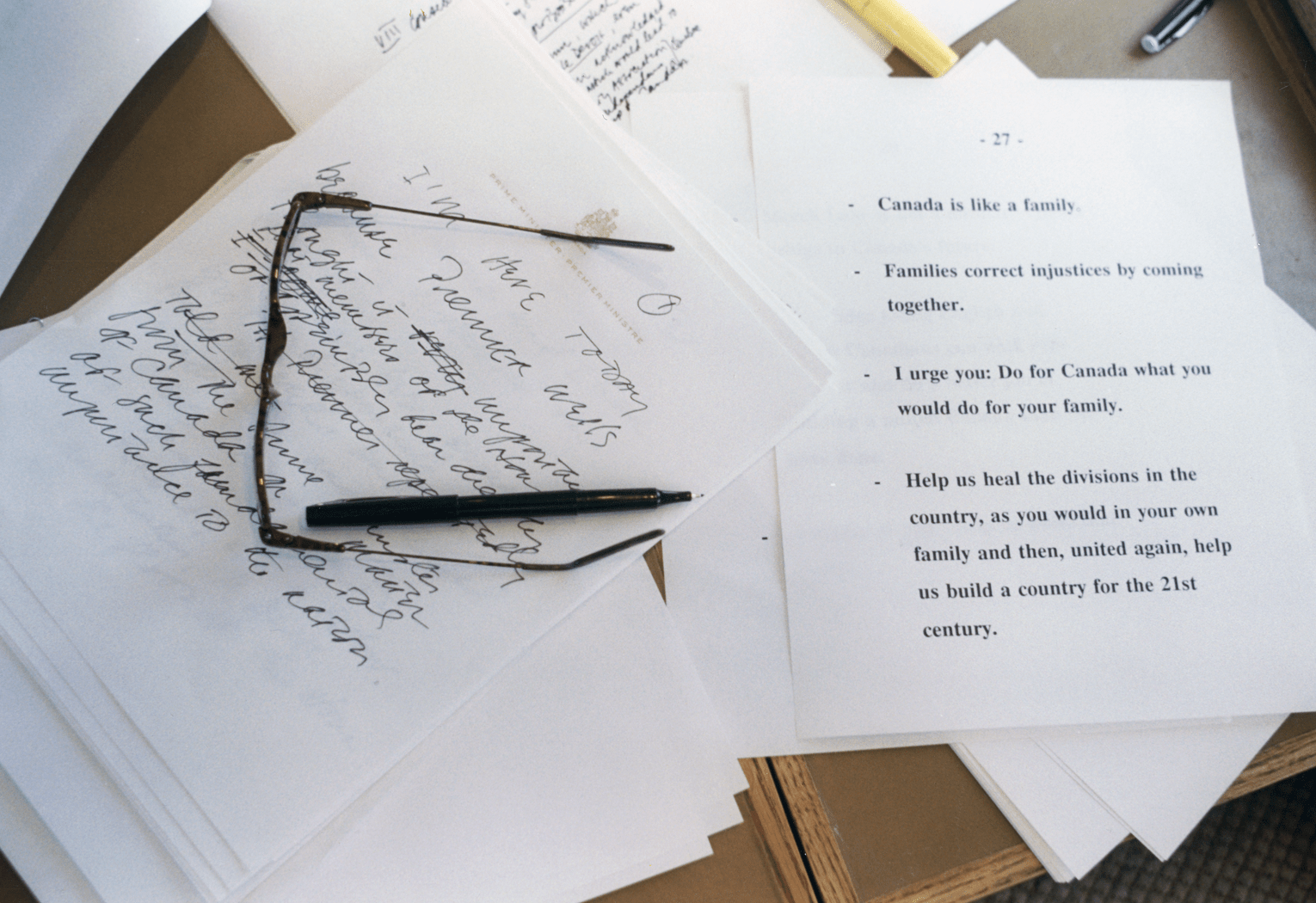

Working with words: Brian Mulroney’s speech editing space/Bill McCarthy

Working with words: Brian Mulroney’s speech editing space/Bill McCarthy

Speech drafts would go home with him to 24 Sussex in his briefcase, and his written comments and notes in black felt pen would usually be returned the following morning.

Along the way, the Mulroneys also raised four children—Caroline, Ben, Mark and Nicolas.

During his years in office from 1984-93, he clearly thought Canada-US relations were the most important yardstick of foreign policy. He used to say that the door to the Oval Office opened all the other doors in Washington. And then some, across America and among NATO allies.

He was the only foreign leader ever invited to speak at the state funeral of not just one but two American presidents, Ronald Reagan and Bush. He also spoke at Nancy Reagan’s memorial service at the Reagan Library in California.

When Reagan came to Quebec City on St. Patrick’s Day in 1985, he joined Mulroney on stage singing a chorus of “When Irish Eyes are Smiling”. It was quite a different scene from Reagan’s first visit to Ottawa in 1981, when thousands of protesters carried placards demanding an end to acid rain.

For Mulroney that was a given, or as Bush once put it after a lunch at 24 Sussex: “I got an earful on acid rain.”

That’s one of Mulroney’s policy achievements. Then there was the Canada-US Free Tree Agreement, centrepiece of the 1988 election campaign, and forerunner of NAFTA, including Mexico, in 1992.

But first Mulroney got himself elected in the 1984 election, with 211 seats in Parliament, the biggest landslide in Canadian history.

Before that, he needed a seat in the House, and got one when Elmer MacKay gave up his seat, Central Nova, in Nova Scotia.

Elected in a walk, Mulroney was welcomed to the House by Trudeau and his wily lieutenant, Allan J. MacEachen, who tabled a motion on minority French language rights in Manitoba in October 1983.

It was the first test of Mulroney’s ability to manage the Tory caucus, a notoriously fractious team. Sure enough, a Conservative backbencher went to see him and said: “I’m sorry the caucus can’t be unanimous.”

“My caucus will be unanimous,” Mulroney replied.

And so it was. The language issue, which had tormented his Tory predecessors, was off the table for good.

And caucus relations became part of Mulroney’s brand.

“You can’t lead without the caucus,” he would say.

In the 1984 summer campaign, Mulroney broke the election open in the leaders’ debate with Liberal leader John Turner defending the slew of patronage appointments left by Trudeau. Turner made them when dropping the writ, saying he had no option.

“You had an option, sir.” Mulroney famously interrupted. “You could have said ‘I am not going to do it. This is wrong for Canada and I am not going to ask Canadians to pay the price.’ You had an option, sir, to say no, and you chose to say yes, yes to the old attitudes and the old stories of the Liberal party.”

Game, set and match.

The 1988 election became a one-issue campaign, in essence, a referendum on free trade. Mulroney and the Tories gained a second majority, partly because the NDP vote grew at the expense of the Liberals.

“Every vote for the NDP is one vote less for the Grits,” Mulroney said one night after a good day on the campaign trail.

And so it went, two terms and out, which had always been Mulroney’s plan. He knew his time in office was coming to an end, and there were other things he wanted to do.

When Mulroney left power in June 1993, he and Mila gave a private dinner for about two dozen friends and colleagues at 24 Sussex. It was June 11, 10 years to the day since he was elected Conservative leader.

In an informal way, he believed the Americans had it right about the constitutional limit of a president’s time in office—two terms and out.

And there were other things he wanted to do, starting with returning to Montreal, where he and Mila bought a penthouse apartment at the top of the hill, with a stunning view of the mountain above, the city below and the river beyond.

Starting his new, post-PM life, he visited his friend and mentor Paul Desmarais at Power Corp. in Montreal.

Desmarais had just one bit of advice on the question of his legacy: “Let the garden grow.”

Did it ever. The tributes at his passing were a reminder of that.

Ian MacDonald, Editor and Publisher Emeritus of Policy Magazine, was author of the 1984 bestseller Mulroney: The Making of the Prime Minister. He served as principal speechwriter to the PM from 1985-88.