King of the Road: Rick Mercer’s Futile, Fabulous Quest to Define ‘Canadian’

By Rick Mercer

Penguin Random House Canada/October 2023

Reviewed by Anthony Wilson-Smith

November 18, 2023

And now, for all present and wannabe Canadians, an informal citizenship test. Name the Canadian who has, at various times, skydived with the Skyhawks; sported a classic, sideshow “beard of bees”; survived a stock-car stunt called, the “train of death”; climbed into a snoozing grizzly bear’s den to tag her ear and cuddle her cubs; and – more benignly but no less impressively – played drums alongside the late, legendary Neal Peart of Rush.

For those who answered ‘Rick Mercer’, muted congratulations and no bonus points. Mercer is among the handful of Canadians who could show up in almost any town in English Canada and be recognized immediately — in part because he’s likely already been there. Now 54, Rick has been a fixture on Canadian television and stages in communities large and small coast to coast to coast since he was 19, when he had his first hit with the one-man play Show Me the Button, I’ll Push It, Or Charles Lynch Must Die. The show was a scathing response to a piece by the legendary political columnist that stretched to absurdity the constitutional parlour game of the day of tossing potential Meech Lake amending formulae into a blender, this time producing the sacrifice of Newfoundland as the price of peace. A son of Middle Cove, Mercer, per the show’s title, was livid.

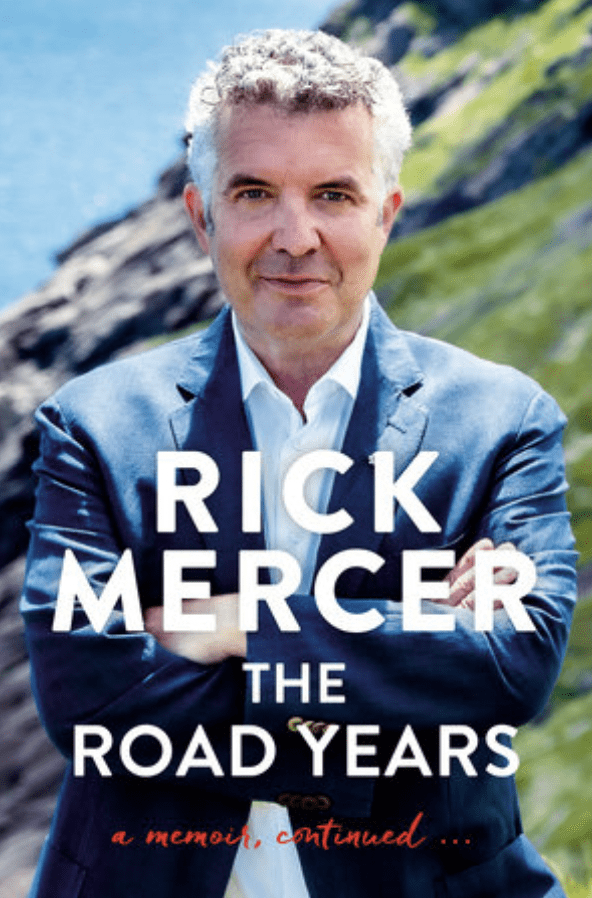

For anyone who somehow missed seeing him in person or on television in This Hour Has 22 Minutes, The Rick Mercer Report or elsewhere since that breakout, he is also a best-selling author whose sixth book now awaits similar distinction. It will almost certainly meet the bar: the briskly-paced, often laugh-out-loud-funny Rick Mercer: the Road Years, is an engaging read that is also a perfect primer on the reasons behind his multi-pronged successes.

The new book comes in the wake of 2021’s Talking to Canadians, and picks up Rick’s adventure-filled walk through life. But where that book was a more personal memoir, this focuses on the backstory behind some of the most memorable segments — there are many — of the long-running Rick Mercer Report. For the few who never saw the show over its 15-year run, Rick and a small production team travelled the length and breadth of Canada searching out unique, sometimes hazardous, occasionally breathtaking claims to fame of often small, otherwise unheralded communities.

Those segments were interspersed with sessions with well-known public figures doing things for which they were not as well known. They included the genial then- American ambassador David Wilkins playing tennis and being cajoled into a kids’ game of street hockey, then-prime minister Stephen Harper, so famously reserved, being relaxed, funny and informal with Rick in a way few Canadians had ever seen; and singer Jann Arden giving a near-spontaneous tour of her beloved Calgary when the two entertainers first met (they have been close friends ever since.) In one particularly memorable clip, Bob Rae, then a Liberal leadership candidate, now Canada’s ambassador to the United Nations (and a regular contributor to Policy), joined Rick for a cheeky skinny dip.

For years, the mere mention of an eccentric local custom or quirkily Canadian ritual could get Mercer and crew flying into a great story on short notice, like comedy correspondents.

Often, the segments were either lightly scripted or not-at-all. That is a seldom-practiced, risky venture, especially for a prime-time production, but in the hands of the quick-thinking Mercer and crew produced far more warming, authentic results than likely would have been the case with a tightly-programmed venture.

A quality that shines through the book – and Mercer’s career – is his self-confidence, in the best of ways. Time and again, he demonstrates a willingness to improvise on the fly, repeatedly leaves centre-stage to his guests rather than himself, and possesses an endearing willingness to mock himself if it brings an extra laugh (as in his G-rated description of an attack of hemorrhoids that launched at a particularly inopportune time.)

For all that he is best known for his rants – stinging analyses of the people and issues of the day delivered while striding down a graffiti-filled Toronto alley – the other part of Rick always in evidence is his love of country at ground level. For years, the mere mention of an eccentric local custom or quirkily Canadian ritual could get Mercer and crew flying into a great story on short notice, like comedy correspondents. One example was their trip from home base in Toronto to a bee colony on a farm just outside Langley, British Columbia, where Mercer allowed roughly a thousand bees to settle on his face per a routine practiced by some beekeepers.

All these exploits were ostensibly in the name of answering the age-old question, “What does it mean to be Canadian?” That is the opening sentence of Chapter One of The Road Years – and in less able, more leaden hands, it could easily have been a recipe for ennui. But Mercer never returns to that question until the final chapter. When he does, he addresses some of the country’s strengths and failings in a typically entertaining way that nonetheless makes a serious point. Canada, he writes, “gave the world insulin, the zipper and the Bloody Caesar…(but) we are also a nation that supported residential schools. And we can’t continue to pretend that never happened.”

After 15 years of exploring the country in a way few others have, Mercer declares he is left with two enduring conclusions. The first is that his willingness to believe he could answer the question of what it means to be Canadian was “pure hubris…a decidedly un-Canadian trait.” The second: “I may not know what it means to be a Canadian, but I do know I have never wanted to be anything else.” The rest of us are blessed for that.

Contributing Writer Anthony Wilson-Smith, President and CEO of Historica Canada, is a former Editor in Chief of Maclean’s.