Raising Canada’s Defence Spending Game to Meet the 2% Pledge

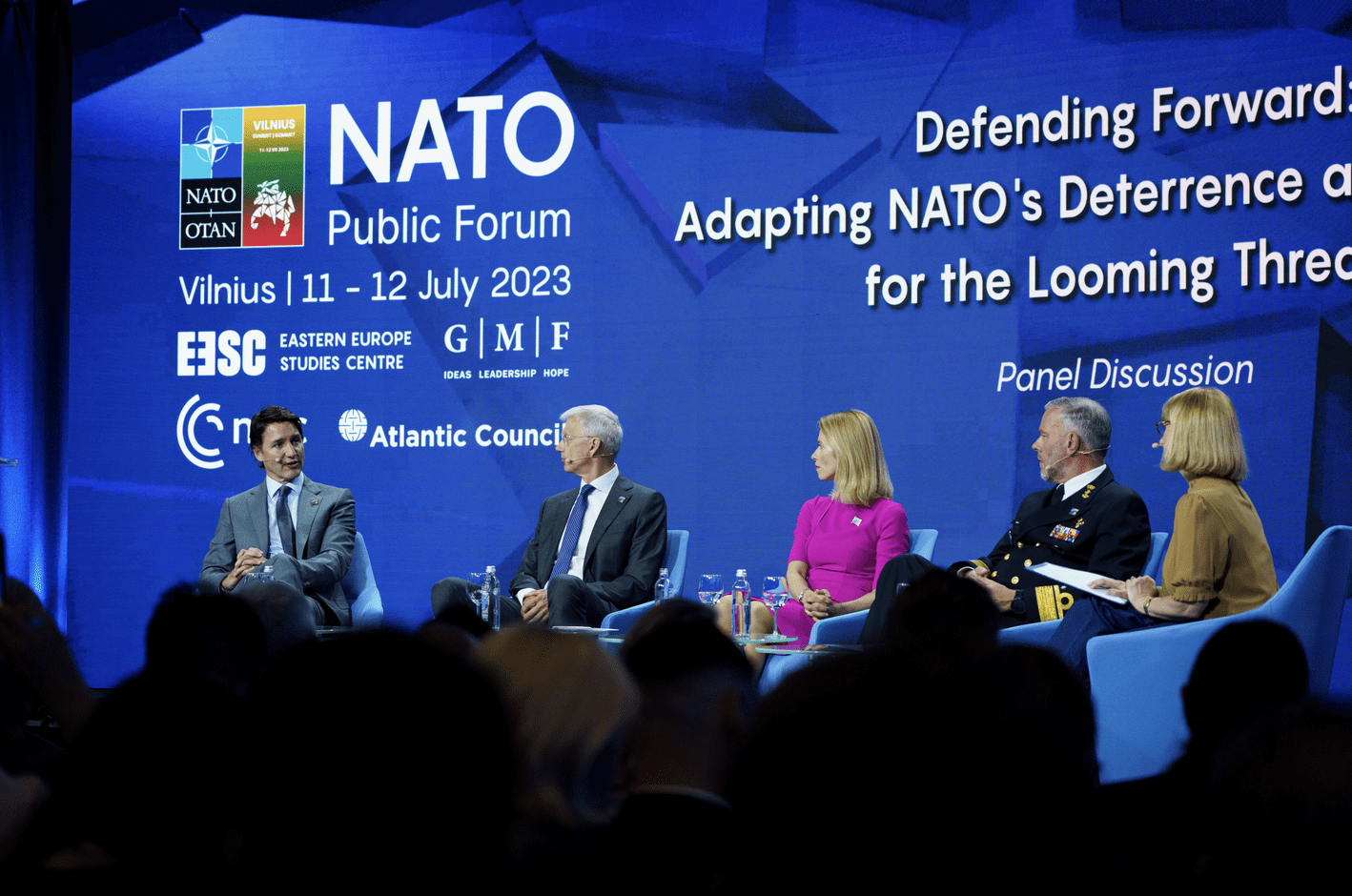

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau at the NATO Summit in Vilnius on July 11/Adam Scotti

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau at the NATO Summit in Vilnius on July 11/Adam Scotti

Robin V. Sears

July 30, 2023

My late grandfather, the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) MP Colin Cameron, was barely seventeen when a German mortar blew his best friend’s head all over him. The experience was so traumatic it made him resolute to never discuss his painful war years. (I know the story only from a private diary he bequeathed.) It also made him a powerful critic of war, and of defence spending. As a politician, he denounced the Spanish Civil War, the Korean War and the war in Vietnam. The one exception he made was the Second World War, which was courageous of him as his leader and many colleagues were pacifists. He defended that war as a necessary confrontation with evil. His attitude to defence spending was not much different from most Canadians, then and to the present day: Don’t fight wars and don’t spend scarce money on them.

Except, of course, we are as wrong today as he was then.

Although they occur rarely, wars against evil require you to fight them and to spend what is required to win them before they erupt, not after; a painful lesson we are all re-learning today. So far, most Canadians support our spending on defeating Russia. But asked to rank defence spending for decades by pollsters, Canadians never place it in the top ten. Our governments learn, not surprisingly, that there is little political risk in ignoring defence. We are not much different than citizens of most of the advanced democracies. The dramatic exception is the United States, most of whose citizens support spending more than C$1.1 trillion dollars on their military, more than the next nine nations combined. We spend about $40 billion, or 1.29% of GDP.

Citizens of European and Asian democracies are also mildly dismissive about defence spending, accepting only a nearly frozen minimum. Polling data going back forty years reveals little change in Canadian attitudes. A recent Nanos poll claims that two out of three Canadians are okay with raising defence spending now.

Pollsters say this uptick in support for defence spending may be transitory, skewed by the horrors of the Russian approach to war — targeting civilians and their homes, schools and hospitals. Other research shows that number shrinks when voters are asked to make a forced choice between defence and health, among a variety of other issues. That support may prove wobbly when voters understand that our commitment will mean $20 billion more for the military, and therefore less for housing and health care.

For the first time in his eight years as prime minister, Trudeau made a public commitment to the NATO summit last month that Canada would meet the target of defence spending at 2% of GDP, after ducking such a promise to our allies for years. The trigger, of course, was Ukraine and the necessary defeat of Russia — if Russia is to be discouraged from launching even more dangerous military adventures against its sovereign neighbours. Finland, Sweden and Germany have each made volte face decisions about better arming, training and deploying an effective military — on their own, and in alliance with NATO partners. Even Japan and South Korea have moved off their ‘defence only’ constitutional constraints, a third rail in each country’s politics for more than 70 years.

Canadians have, however, a unique reason for our limited commitment to defence spending: geography. Having become anxious about our former colonial masters’ willingness to defend Canada after WW1, we decided to put ourselves in the embrace of the only likely attacker, the United States. Beyond our spending here, we jointly pay a share of the cost of NORAD, to defend the continent; to NATO to defend the West. But our spending is a tiny sliver of the total. And the Americans, and other allies, are getting irritated that our sliver grows smaller by the decade.

It will be hard for the Trudeau government, or for that matter any other government, to defend the necessary cost of effective national security, let alone the dues of security club membership, for many reasons apart from our complacency about the U.S.

First among them is the shambolic approach to management, procurement, and simple competence among our political and military leaders. Yes, we have highly trained, respected and skilled men and women in the Canadian Armed Forces, and some good military leaders, but every year we have fewer of each.

It will be hard for the Trudeau government, or for that matter any other government, to defend the necessary cost of effective national security, let alone the dues of security club membership, for many reasons apart from our complacency about the U.S.

One obvious reason is that we pay a first-year soldier less than half what we pay a city cop or a plumber. Yes, they receive full room and board and good pensions, but on starting day the average soldier receives $49,400 dollars a year, or $24.70 an hour. Recruitment is falling for several reasons, not least among them the inability of the CAF leadership to paint an attractive and persuasive picture about the prestige, skills and network you will acquire in our navy, army or air force. But a close second is surely the insulting pay scale.

Canada is a rich and successful country, but at only 40 million people we can’t afford to run our armed forces with the best equipment for every military capability on land, at sea, in the air and in space. Yet, we are always determined to buy the most expensive — and the most expensive to operate — military kit, such as the next generation fighter, the F-35, the most expensive in the world. The F-35 is designed as a first strike, heavily-armed, technologically unmatched weapon of war. Against whom is Canada going to launch a first strike, ever?

This is only the latest defence procurement head-snapper. In order the keep them happy, we almost always buy American, but the respected Swedish Grippen fighter is much cheaper to operate and costs less than half as much to buy. Among the rationales governments offer for such profligacy is that the F-35 will generate hundreds of millions in revenue, and thousands of jobs, in Canadian suppliers’ participation in their production. Even ignoring governments’ perennial over-stating of those benefits, there will still be only $5 billion, at most, in offset revenues — less than 25% of what we are spending on these jets. Using defence procurement as a form of industrial development policy is a madness that most countries are addicted to. So is spreading the spending widely and therefore winning broad local political support.

Some years ago, I toured one of the dozens of suppliers necessary to build a Chinook helicopter. This firm did only the rotors. I naively inquired whether it would not make sense to have the same plant build the choppers’ blades and attach them to the rotor that drove them. After a moment’s incredulous silence, the company CEO said simply, “This helicopter has 19 plants to build it, sited in 16 states, and we are working on one more.” Feeling stupid, the penny dropped on me with a heavy thud. Our two new icebreakers are built in only two places: Vancouver, where a firm was created to build one who had zero icebreaking manufacturing experience; and the other at the Davie shipyards in Quebec.

Do you think that the project’s staggering cost overruns and delay — from a launch price of only $1.3 billion, the ships are now estimated to cost more than $7.25 billion — might have been compounded by not building them together as one project. More radically, we could have bought excellent ships from one of the Nordic countries — who, after all, have been building the best icebreakers for generations — for a fraction of the price ?

So, we barely pay our soldiers a living wage, we default to the most expensive military equipment available, and we waste billions annually on political pork. It gets worse.

Each military service clamours for its best new toys, but we have no way to make expert judgments about which we must have and which are the best value. We have no expert decision-making table, where the prime minister and key ministers hear from external defence experts, none of whom is/was either a member of one of the services or a defence equipment maker.

We need a forum where the pie cannot be added to, but which decides what sized slice each project gets. That decides on the necessary trade-offs between buying submarines, tanks, jets, and armoured vehicles because we can’t afford them all. Each service fights for its most desirable toys, usually having decided before a ‘competition’ is launched on which product they want. No one plays referee on the basis of evidence and numbers — merely politics. One cabinet presentation on procurement made by the military recently had as one of its slides a lovely full-colour photo of one defence multinational’s offering — before the project competition had even been launched. An embarrassed silence must have greeted the naive minister who said, “I thought this was supposed to be a competition?”

If any Canadian government is going to succeed in selling Canadians on the value of raising our defence spending by $20 billion, each of these failures must be addressed. First, we must honour and pay our soldiers, sailors and air force personnel a decent salary. Second, we must have a streamlined and civilian-led procurement policy committed to getting the best product for the best price from anywhere in the world. Third, we must focus on those areas that are most important to Canada and in which we have special expertise. Then, that new forum must have searching and effective project oversight, capable of handing out penalties to those who fail to deliver on time on budget.

We do have special national security skills few others do. Canada has become a military specialist in space, for example. We have developed companies and skills focused on intelligence gathering and the necessary equipment for it in space. We spend a fraction of our defence budgets on it. We have unique and long-term skills at peacekeeping. We have let them wither. We are seen as among the most successful military training experts, across languages and cultures, in the world. It’s a very high payback for our defence dollars, one that was crucial to Ukraine and the Baltic states.

Having made those pledges on focus and performance, and created the infrastructure to execute them well, only then is there a possible political message that might strike more Canadian voters as a somewhat plausible case for greater defence spending. Our military and civilian leaders can then deliver a more credible case to our citizens: we now have a sound security strategy. One that is based on our needs and our focus on what we do best.

We helped create NATO, partly in recognition of the importance to Canada of such an alliance. Our membership today requires that we are seen to be keeping our contributions to the alliance in proportion to our size — and our affluence. We benefit enormously from the intelligence and defence co-operation we uniquely enjoy with the United States. Putting that at risk by failing to help upgrade NORAD, or failing to meet our spending pledges would be singularly irresponsible.

We need to spend more, spend it better, and do it transparently — as the table stakes for our membership in the most powerful military alliance the world has ever seen — and because it is essential to Canadian national security.

Contributing writer Robin V. Sears, who has lived and worked as a political staffer and policy advisor in Europe and southeast Asia, is an independent consultant on crisis communications based in Ottawa.