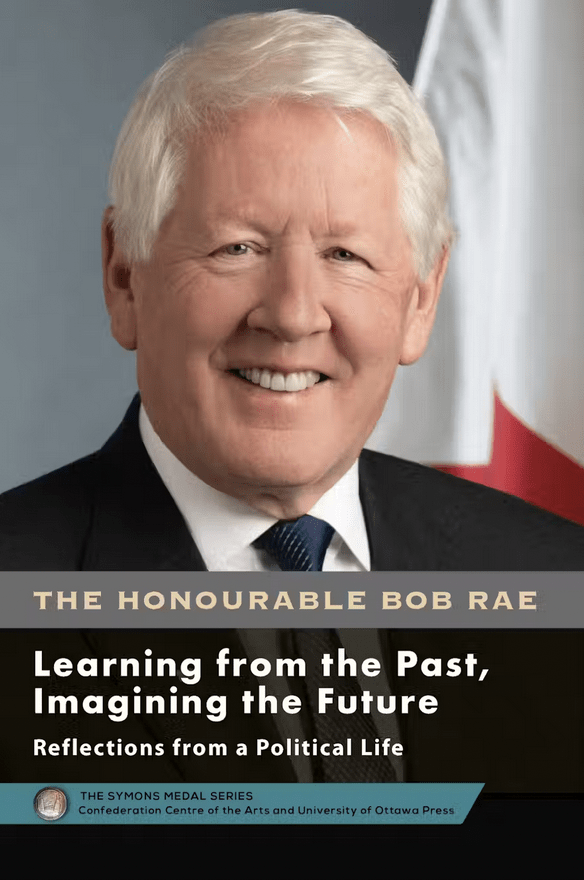

True Believer: Bob Rae’s ‘Learning From the Past, Imagining the Future’

Learning from the Past, Imagining the Future: Reflections from a Political Life

The 2020 Symons Medal Lecture

By Bob Rae

University of Ottawa Press/April 2023

Reviewed by Michael Ignatieff

June 11, 2023

Bob Rae’s Symons lecture, delivered at the Charlottetown Confederation Centre in 2020, and now published by Ottawa University Press, is an eloquent reflection on a life in public service that began with Rae’s election to Parliament in 1977, at the age of 29, and culminated in his appointment as Canada’s Ambassador to the UN in 2020, at the age of 72.

His lecture honours another Canadian public servant, Tom Symons, who founded Trent University in the early 1960s, and who died last year. When Bob met Tom before the lecture to seek advice about what to say, Tom told Bob to make the lecture personal and visionary. It is both.

The lecture offers revealing insights into the history of Canadian progressivism in the late 20th century. It illuminates the links that have braided together the competing strands of our progressive traditions. Long-time Conservative Premier of Ontario, Bill Davis, liked to tease Rae that he was really a Red Tory in disguise, and the friendly dig takes me back to a vanishing political landscape where a cautious, incremental progressivism was a creed that crossed party lines.

This common creed was non-sectarian and broad-church. The right end of the spectrum was occupied by Red Tories such as the philosopher George Grant and Progressive Conservative politicians, including Bob Stanfield, Bill Davis, Peter Lougheed and Brian Mulroney. In the centre of the progressive formation were the Liberals. Mike Pearson’s memorable minority government of the 1960s defined the progressive agenda for the generation — mine and Bob’s — who came of age in that era. That teetering, tottering government, widely derided at the time, left behind the most impressive legislative achievement of the 20th century: the flag, the Canada Pension Plan, Expo 67, health care, the opening to Quebec, and, largely unnoticed at the time, the opening of our border to immigrants from Africa and Asia.

Liberals, being the arrogant and entitled folk we are, like to think we’re the ones who built a compassionate Canada, but truth be told, the achievement, such as it was, was the work of three traditions, conservative, social democratic and liberal, co-operating together. Bob Rae came to maturity in this overlapping competition for the centre of Canadian political life. He joined Pierre Trudeau’s Liberal leadership campaign in 1968 and then graduated towards David Lewis and Ed Broadbent’s NDP after time at Oxford as a Rhodes scholar, coming under the influence of the British left, and then shifting farther left thanks to his work with the union movement as a labour lawyer. Moving from the Liberals to the NDP in his twenties, and back from the NDP to the Liberals in his fifties, may have looked like crass expediency at the time, and I was one of those who thought so then.

In hindsight, Bob’s move back and forth across party lines reflected his conviction that there was a single progressive tradition, with left and centre wings, and he could serve progressive ends by joining up with different wings of the same family. He always argued, when he left the NDP, that he hadn’t left the party, the party had left him. Inside that fractious family, he remained in the party’s centre, and when he came back to the Liberals, his worldview didn’t change much. The lecture shows that Bob Rae remains what he always was; a moderate progressive, socially compassionate, fiscally responsible internationalist, with a commitment to Canada as a pivotal multilateralist, devoted to keeping the world at peace.

In the 21st century, this centrist progressivism is still holding together, at least sufficiently to enable the NDP to stay in a confidence and supply agreement with the Trudeau government. But Canada has lost, and perhaps forever, the progressive conservative element that kept the whole political system from drifting too far left. Progressive conservatism still has its avatars. A Michael Chong or an Erin O’Toole would still fit that description, but their party has deserted them. Canadian conservatism risks becoming a strange brew of imported American bile, populist trash talk and aggrieved Western ressentiment. It isn’t even distinctively Canadian. It’s ‘suiviste’, as the French would say, with Pierre Poilievre following the rightward, populist march of global conservatism elsewhere, in France with Marine Le Pen, in Hungary with Viktor Orban, in Poland with Jaroslaw Kaczynski, and leading the pack, Donald Trump. Whether Canadian voters, fundamentally conservative and cautious by nature, recognize themselves in this alien politics of resentment is less than clear. What is certain is that the old alliance among Red Tories, Liberals and social democrats is dead and gone.

The consensual progressivism of the 50s and 60s rested on a vanished equilibrium of relative equality and high taxation, left over, as Thomas Piketty reminds us, from the heroic years of World War II. Inequality has surged since the 1970s, and it has broken apart the electoral consensus that supported high taxation in return for high-quality public services. So, it’s unsurprising that the liberal elites who rode to power on the back of this consensus are fighting for their political lives. Rae’s Ontario government in the 1990s went down to defeat when a global recession destroyed the viability of his progressive policies.

Rae, like me, is a charter member of that old liberal elite. Roommates while at the University of Toronto, we both enjoyed prestigious educations at Oxford and Harvard, and we benefited from the incalculable advantage of fathers who ended up as ambassadors. So, we both know elites from the inside, but Bob’s career shows that he also knew something about the responsibilities of privilege. He has given back to his country throughout his life.

Still, no matter how public-spirited liberal elites claim to be, a critique from the right of their entitlement, privilege, and yes, their arrogance, was bound to come sooner or later. The problem with the conservative populists de nos jours is they have no solutions to propose to our discontents, except to replace the liberals with a new elite composed of themselves. Instead of working to stabilize and reverse inequality, their economic ideas — tax cuts and more tax cuts — are bound to increase it. Instead of trying to bring a fragmented and fractured political culture together, they cultivate the culture wars, promoting divisive wedge issues largely irrelevant to the real problems the country faces. In his Symons lecture, Bob adopts a tone of statesmanlike detachment and avoids political shots at the current batch of Canadian conservatives, but their rightward populist turn is an unwelcome new development, likely to destabilize Canadian politics for some time to come.

The nastiness of 21st-century politics makes it easy to wax nostalgic about the vanished comity of the century now past. We should remember that the pipeline debate of the 1950s was as nasty a squabble as Parliament has ever seen, and the mutual hatred of Pearson and Diefenbaker, especially during the Munsinger scandal, was palpable. Parties and politicians fought each other with as little respect for the parliamentary proprieties as they do today.

The lecture shows that Bob Rae remains what he always was; a moderate progressive, socially compassionate, fiscally responsible internationalist, with a commitment to Canada as a pivotal multilateralist, devoted to keeping the world at peace.

What was different then was that tactical political combat hid a degree of strategic agreement on the Canadian fundamentals. As a young parliamentarian, Rae himself tabled the motion that brought the Clark government down in 1979, leading to the return of Pierre Trudeau. Rae, Trudeau and Clark may have been political antagonists, but their overall vision of Canada, and what government ought to be doing to realize our promise, shared a lot in common. Today, it’s an open question whether that common ground remains.

Here, too, we need to avoid overdoing the nostalgia. That would ignore the divisive constitutional debates of the 1980s that Bob returns to in the lecture. Even within a political culture that in retrospect seems consensual, there were important differences of principle that became more evident as the euphoria of 1960s was followed by the darker and more difficult 1970s and 1980s. Rae’s lecture makes it clear that he dissented from the centralizing ambitions at the heart of Trudeau’s vision of Canada. His time as premier of Ontario seems to have deepened this conviction:

“The notion that power must be unitary, and that sovereignty is the be-all-and-end-all, was not natural then, and is not natural now. Government institutions that are over-centralized do not work well — at their best they are sclerotic and hierarchical — at their worst they are corrupt, authoritarian, and dictatorial. Canada’s working idea is pluralism, which accepts the limits of sovereignty and nationalism, and stresses the need for cooperation between governments.”

The drift of Canadian politics since Pierre Trudeau’s time confirms that Rae had a sound political instinct about the country’s limited taste for centralized government. Instead of a country bound together by a common Charter and a repatriated constitution, as Pierre Trudeau imagined, even his son has taken a different road. The country, when it works at all, works when Ottawa proposes, but the provinces dispose, Ottawa providing the tax resources and the provinces implementing programs in their own fashion. Such common purpose as we ever achieve comes as the result of protracted negotiation between the centre and the provincial capitals. Rae was one of those in the NDP caucus in the constitution debates of the 1980s who campaigned in favour of two constitutional changes that drove the federation towards a more decentralized model: the entrenchment of Aboriginal rights and provincial title to natural resources.

The benefits of this kind of decentralized federalism are clear. After hundreds of years of exclusion, Aboriginal Canadians are at the table. Rae has been a consistent and courageous believer in Aboriginal rights and Aboriginal inclusion. The downsides of our constitutional compromise are also evident: it takes a long time to get anything done. We have a lot of veto points, and Aboriginal Canadians now have vetoes too. We have chosen justice and inclusion at the price of forward motion: whatever the issue, whether climate change and other pressing issues, like improving our competitiveness, dismantling our internal trade barriers, our professional licensing monopolies that hold back entry of newcomers to our professions, we’re moving slowly, but that has been our collective choice. What price we will pay when other countries move faster, only time will tell.

In foreign affairs, Rae has stayed true to the mid-century multilateralism and internationalism of Canada’s progressive high noon. He’s been special envoy to Myanmar and wrote a scathing report denouncing the Burmese military regime’s treatment of the Rohingya people, and now he’s our ambassador at the United Nations, reprising a role once performed by his father, and by mine.

Our fathers, who were rivalrous friends throughout their careers, rose within the fabled Department of External Affairs in the Pearson era. This was a time when, once a decade, Canada could get the votes for a seat on the UN Security Council. Those days are gone. Other countries, such as Ireland and Portugal, have more friends in Europe and the developing world, and in the so-called Global South, Canada is seen as too NATO, too close to the US, to be voted onto the UN’s top body. Rae does not mention our country’s declining stature at the UN and other multilateral bodies. Some of this decline is the inevitable result of the rise to power of China and its allies, especially Russia, Brazil, India and South Africa, and the shift of global wealth eastward. The mid 20th-century world in which we counted—the world whose axis was the North Atlantic—is gone.

The axis of global economic and political power has shifted eastward, and in this new world, Canada is not a middle power, but a marginal one. It also made a bet on ‘soft power’ as a lever of influence, and this has turned out to be a poor choice in a world where power comes from the barrel of gun. Rae’s lecture stays irenic, hopeful and rhetorical, but I’m sure he is as impatient as I am with a Canada that thinks foreign policy is the art of virtue signalling, accompanied by photo ops. His father and mine knew better. They had been through a world war. Foreign policy is the defence of national interests, with all the sinews of national power, joined to a commitment to uphold an international order that keeps the peace. In recent decades, we’ve had a foreign policy — across Conservative and Liberal governments alike — that expounds values without resources and expresses solidarity without staying power. These are the symptoms of a comfortable country unwilling to face international decline. Ukraine is a wake-up call. They don’t need our speeches. They need money and they need weapons, and we’ve had to deplete our military stockpiles and capability even further to equip them in their fight.

As anybody who has read this far surely knows, Bob and I were friends before we became rivals for the leadership of the Liberal Party. We both wanted the same thing, and in the end neither of us won the ultimate prize. That’s politics. Reading this lecture enabled me to look back on all that rivalry with fresh eyes and to realize how similar our views of the world were, how we came out of the same formative times, and how, in his case certainly, he stayed true to what he believed when I first met him, all those many years ago.

Michael Ignatieff is Rector Emeritus of Central European University and a professor of history, based in Vienna.