Policy Dispatches: Business, History and a Dance Party in West Africa

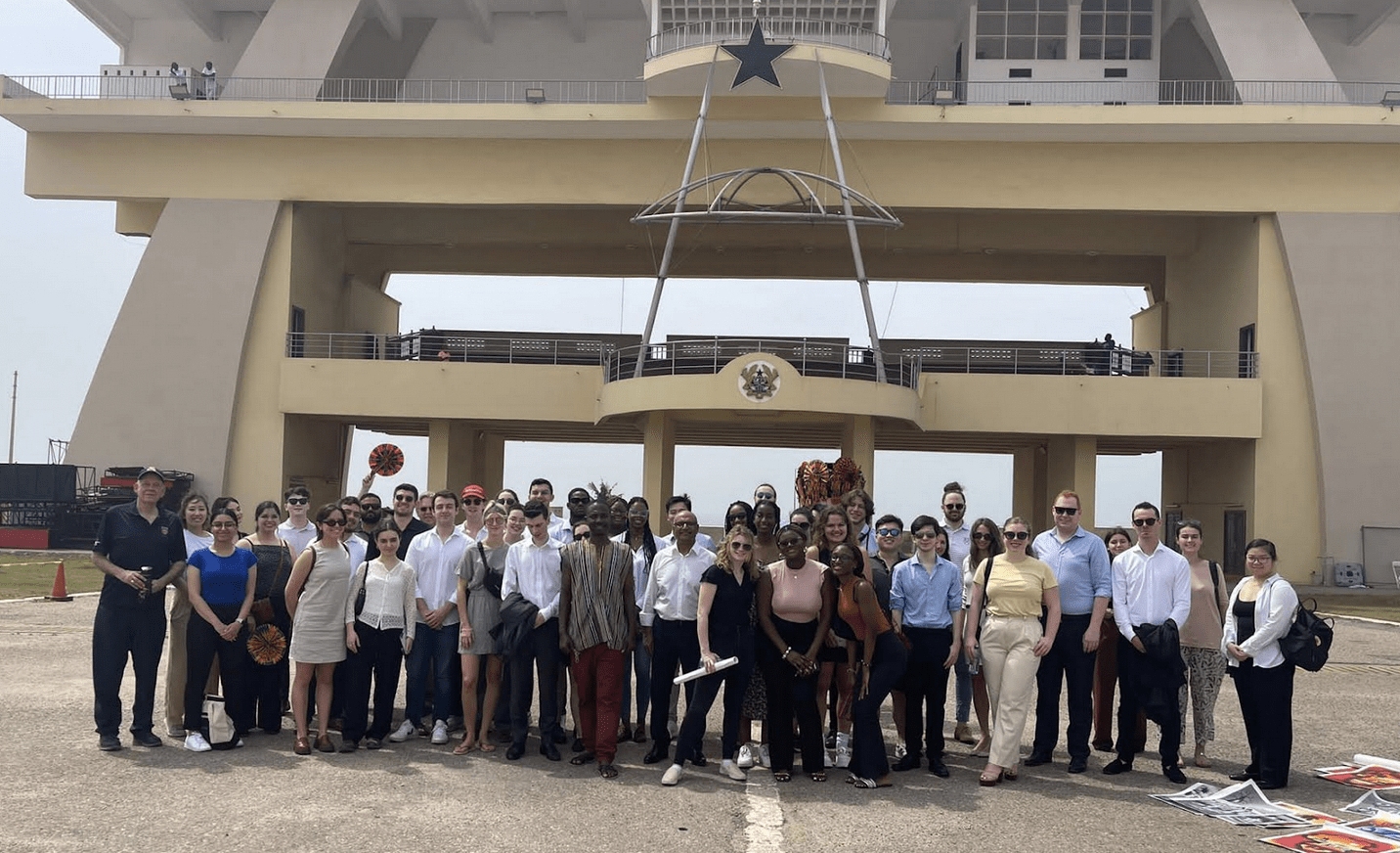

McGill management professor Karl Moore (far left) and students at Black Star Square in Accra, Ghana

McGill management professor Karl Moore (far left) and students at Black Star Square in Accra, Ghana

By Karl Moore and Campbell Clarke

April 20, 2023

Policy Dispatches are pieces combining travel, policy and political writing from Policy writers on the road.

So much of business and management education is theoretical — well-reasoned systems and formulations produced by brilliant thinkers from the world’s top business schools designed to arm BCom and MBA students against the possibility of failure. While theory, case studies and mogul memoirs are all useful, exposure to business leaders around the world — from storefront entrepreneurs to policymakers to CEOs — provides an invaluable window on the confluence of economics, commerce, culture, finance, and competitiveness that impacts human lives.

That was the thinking that launched McGill University’s Hot Cities of the World Tour for undergrads, alumni and professors from the university’s Desautels Faculty of Management.

In 2009, the program’s first year, 20 business students from McGill and 20 from Western University’s Ivey Business School, supported by Gerry Schwartz of Onex Corporation and his wife, Indigo Books CEO Heather Reisman, visited Israel. The following year, 30 students travelled to Abu Dhabi and Dubai and the Hot Cities of the World Tour became an annual event.

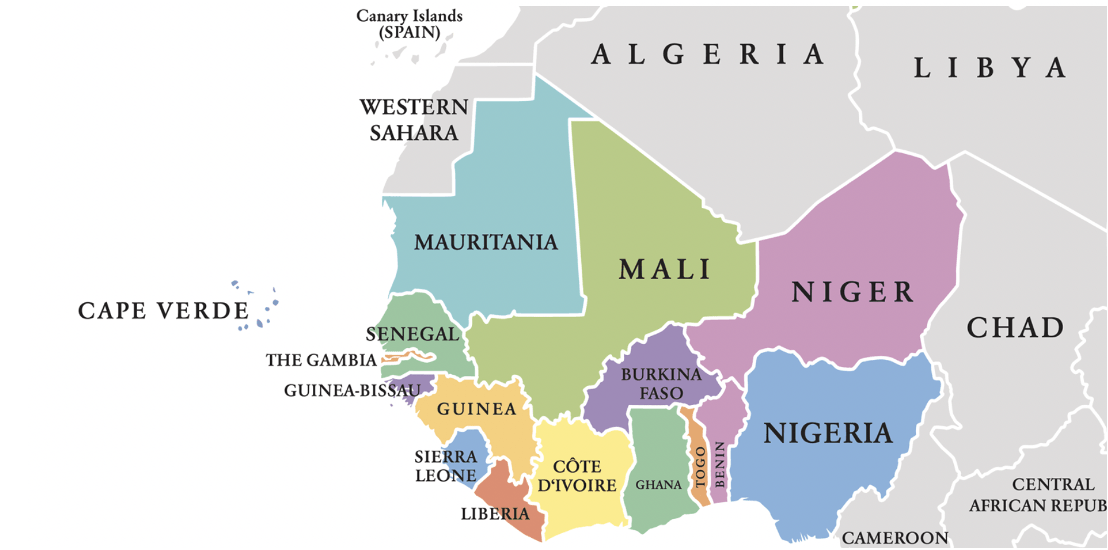

Wikipedia

Wikipedia

This year, for 12 days in late February and early March, 50 of us from McGill visited Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. The group included 30 undergrads — including Campbell Clarke, co-author of this dispatch, one management professor — Karl Moore, the other co-author of this dispatch — and 19 alumni.

Over the years, we’ve visited India; South Africa; Russia; Mongolia and Seoul; Chile and Colombia; Indonesia and Qatar; Malaysia and Hong Kong; the Philippines and Singapore, and in the last year before the COVID pandemic, Tokyo, Bangkok, and Hong Kong. This year, after a three-year COVID-mandated hiatus, we returned to Africa.

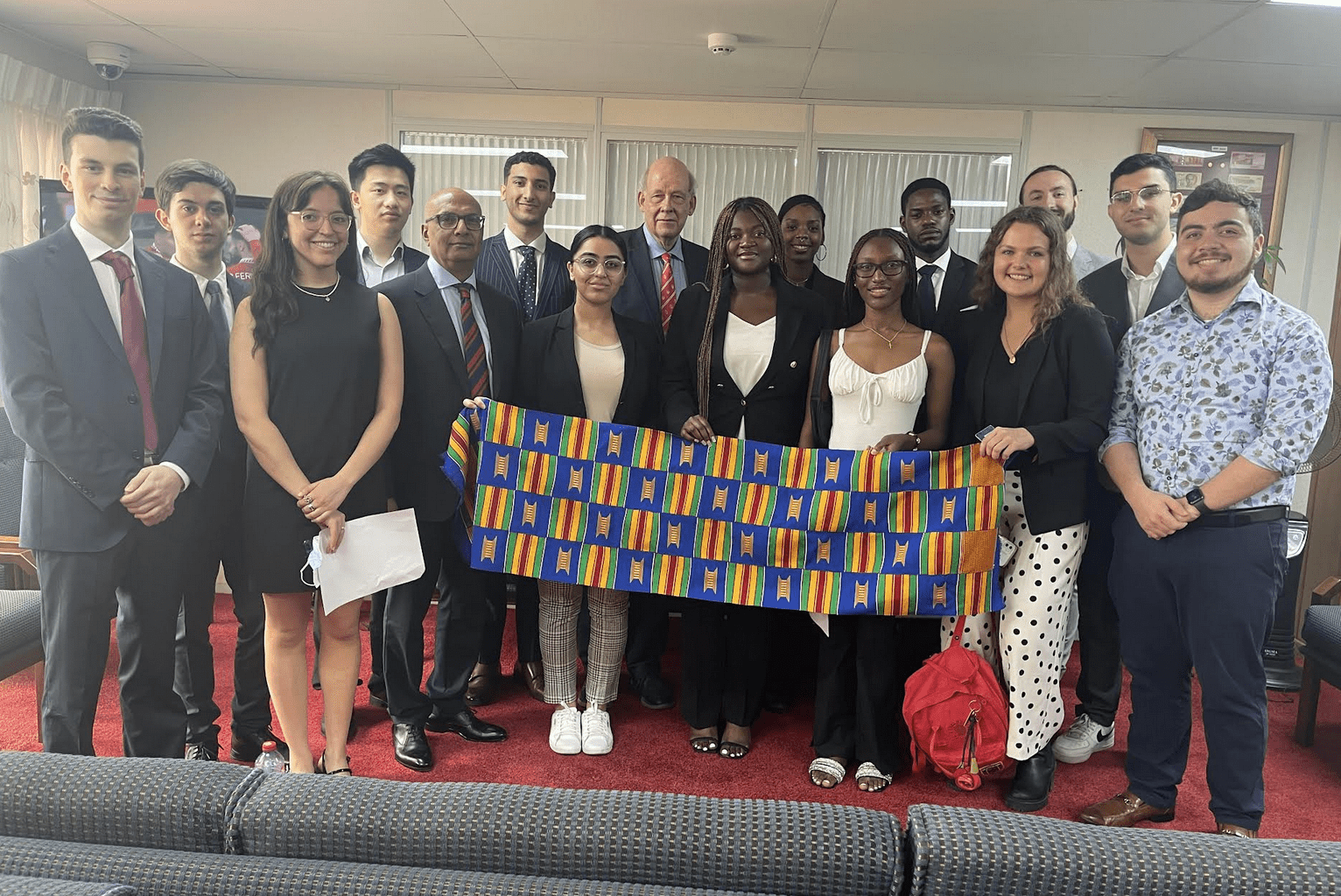

Visiting with McGill economics grad and Governor of the Bank of Ghana, Dr. Ernest Addison

Visiting with McGill economics grad and Governor of the Bank of Ghana, Dr. Ernest Addison

Why Africa in 2023? The continent is, in so many ways, the heart of our world, yet Africa’s diverse cultural and economic influences long remained understated as a global story. During the last twenty years, a map of Africa was displayed on the cover of The Economist on only three occasions. In 2011, the Economist cover read: Africa Rising: After Decades of Slow Growth, Africa Has a Real Chance to Follow in the Footsteps of Asia. Then, in 2013, Aspiring Africa provided a 14-page report on the world’s fastest-growing continent. “Never in the half-century since it won independence from the colonial powers has Africa been in such good shape,” read the leader. “Its economy is flourishing.” Most recently, in March 2019, The New Scramble for Africa: And How Africans Could Win It, was published. “Governments and businesses from all around the world are rushing to strengthen diplomatic, strategic and commercial ties. This creates vast opportunities,” The Economist proclaimed. “If Africa handles the new scramble wisely, the main winners will be Africans themselves.”

Karl has travelled to Africa eight times during the last 35 years. He has friends in various capitals and extended family in South Africa. Since his first trip to Ghana in the early 1980s, his appreciation of the continent’s history, compelling contradictions, diverse cultures and breathtaking beauty has only grown. In recent years, during what McKinsey has called “Africa’s business revolution”, he has studied the continent from a business perspective: what distinguishes first-generation mobile magnates like Naguib Sawahiris of Orascom and Mo Ibrahim of Celtel from their North American, European and Asian counterparts; how is Nigeria’s Nollywood film industry different from the business models of Hollywood and Bollywood; how is the global success of Afropop exemplary of small-world cultural disruption; how have the indomitable women who’ve long been the backbone of the continent’s socioeconomic infrastructure been empowered by business innovation from microcredit to tech startups — and what barriers do they still face? “Despite the fact that women run most small and medium scale businesses in Africa,” Quartz reported in September, 2022, “they have a $42 billion gap in funding versus men.”

Telling the story of our trip at Deloitte Ghana

Telling the story of our trip at Deloitte Ghana

During our trip, CEOs and government officials would call Karl — as the elder of our group, highly respected as the voice of experience in African culture – to the front of the room to tell the story of our trip and to explain why we had chosen to visit Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. At Deloitte Ghana, there was quite a group to address as it included our 50 members from McGill University and at least an equal number of Deloitte employees. We had asked Deloitte and other organizations to invite some of their Gen Z employees to the meeting so that our Gen Z students could speak with younger people from Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire to get a sense of what their lives were like. This also reflected Karl’s interest in the Gen Z perspective explored in his latest book, Generation Why: How Boomers Can Lead and Learn From Millennials and Gen Z. The Gen Zs from Africa were equally intrigued to meet Gen Zs from our part of the world, and together, we began to debate the question: why, beyond our interest in the economy, did we choose to travel to Africa?

After a couple of tries, and with some input from the students – what we call reverse mentoring – we came up with a more fulsome explanation as to why we chose West Africa for this year’s tour. As a mission statement, it evolved over time, becoming more refined as we gained insights from new meetings and from our experience amid the complex realities of today’s Africa.

Students at the Sky Bar 25 in Accra, Ghana: Imane Enette, Hawa Keita, Julia Ayim, Joy Sebera, Bo Wen Chen, Claudestine Williams-Tucker, Leo Normandin, Neva-Jade Kadende, Aïssatou Fanny, Josué Anagonou

Simply put, we were there because Africa is critical to the future of the world. The window provided by Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire on that future through its business, governance and cultural narratives is just one way to understand how and why.

This is partly due to the continent’s demographics; the birth rate, unlike in much of the world, is increasing. Africa has the world’s youngest population. According to Statista, the 23 countries with the lowest median age are in Africa. Many parts of the world need African immigrants, especially Canada, which welcomes newcomers from both English- and French-speaking African countries, with African-born individuals comprising 13.4% of recent immigrants to Canada as of 2016. That number is growing. Ghana — a former British colony that declared independence in 1957 but remains a member of the Commonwealth and whose official language is English — has a vibrant diaspora community in Canada, centered mostly in Toronto. Côte d’Ivoire, a former colony of France that became independent in 1960 and whose official language is French, has a population, like Ghana’s of about 30 million. Both countries are democracies coping with the same democratic disruptions that have influenced outcomes in larger African countries from Algeria to Zimbabwe, including technology, propaganda and foreign investment by China and Russia.

Beyond demographics, Africa also possesses a significant portion of the world’s resources – resources that, more than anything else, are essential to help us create electric vehicles and other technologies that reduce our carbon footprint. To sustain a world run on computers, cell phones, and other technologies that require microchips, Africa’s mineral resources, like Canada’s, will be crucial. As the transition to a clean-energy economy takes hold, the critical minerals required for electric-vehicle batteries will be in especially high demand.

We heard and read about the growing influence of China and, to a somewhat lesser degree, Russia, in Africa, a force to which the West must provide an adequate alternative. Africa will help determine whether the current challenge to the liberal, democracy-led world order by authoritarian countries succeeds or fails. Some Africans are well aware of this issue; Celtel founder Mo Ibrahim, who has in many ways become the face of political reform in Africa, is one of them. In 2007, he initiated the Ibrahim Prize for Achievement in African Leadership, which provides USD $5 million African heads of state who deliver security, health, education, and economic development to their constituents and democratically transfer power to their successors.

As we spent more time in West Africa and learned more about the region, Karl’s front-of-the-room speech evolved, and he began discussing what Africa has to teach the rest of the world. What struck us most, beyond demographics and resources, is that it is time that the world learn more about how to live from Africa and its people. Not to say that Africa doesn’t face major challenges economically and politically, but in too much of the world, especially in North America, our cultures are far too individualistic; too much about “I” and not enough about “we.” In West Africa, we saw and experienced a sense of “we” that informs not just social structure but business and political culture, with the importance of close and extended family the nucleus of a worldview based on multiple levels of a single, interconnected community.

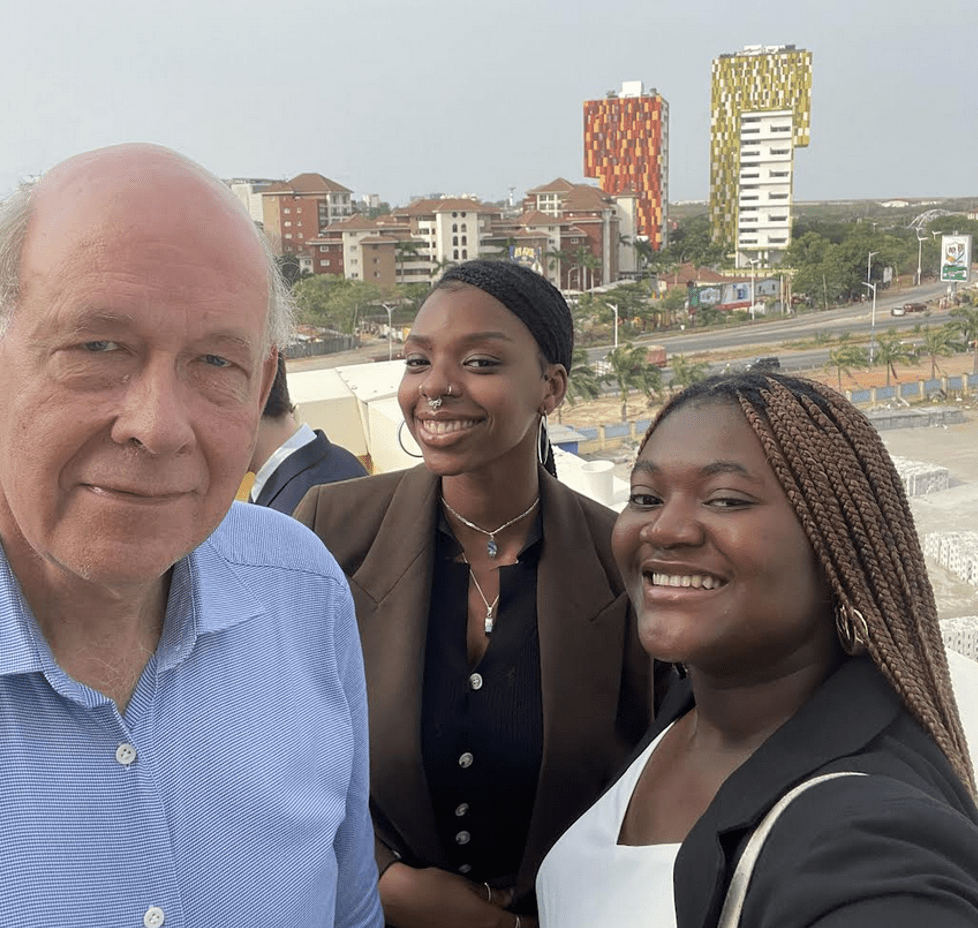

Karl with students Imane Enette and Julia Ayim

Among the indelible memories of our trip was a dinner at the Azmera Restaurantin the Ghanaian capital, Accra. One of our undergraduate students, Julia Ayim, is from Accra, and her family suggested this lovely restaurant with authentic Ghanaian food. But it was the music that transformed the evening as the live band playing Ghanaian music propelled us all out of our seats and onto the dance floor, soon joined by several local McGill alumni and Accra business leaders, which made for quite a scene — the whole restaurant becoming an international dance party befitting the house specialty of United Nations soup.

Bearing witness: learning about the inhuman conditions of slaves awaiting transport

Bearing witness: learning about the inhuman conditions of slaves awaiting transport

The emotional contrast of that night with our pilgrimage to the Slave Castles of the Cape Coast — monuments to the enduring shame of our trans-Atlantic history — was overwhelming. Many of us wept as we stood in the dark, constricted room where hundreds of Africans were once held for weeks without toilets, with little food, and often, with diseased corpses strewn among them, waiting to be among the thousands of human beings a year shipped as slaves to plantations overseas. It was an experience to which words cannot possibly do justice.

At the Village of Hope orphanage

At the Village of Hope orphanage

The next morning, after a two-hour bus ride, we visited the Village of Hope Orphanage on the outskirts of Accra, where Julia Ayim’s father, Sam, serves on the board of directors. The Village of Hope is divided into houses, each headed by a mother and father who care for their own children but also for orphans in a family setting. We shared lunch at tables in small groups with members of different houses to learn about life in the Village of Hope. It was an experience that underscored the African values of human kinship and community.

Africa is indeed important to the future of the world, now more than ever. We are already planning our Hot Cities of the World Tour 2024, hoping we can visit Egypt and Morocco, or perhaps Kenya and Rwanda. Africa calls, the future calls.

Policy contributor Karl Moore is an associate professor at the Desautels Faculty of Management. Campbell Clarke is an undergraduate student at McGill in Strategic Management and History.