Policy Dispatches: Bilateral Bonding and Brexit Regret in Not-so-Swinging London

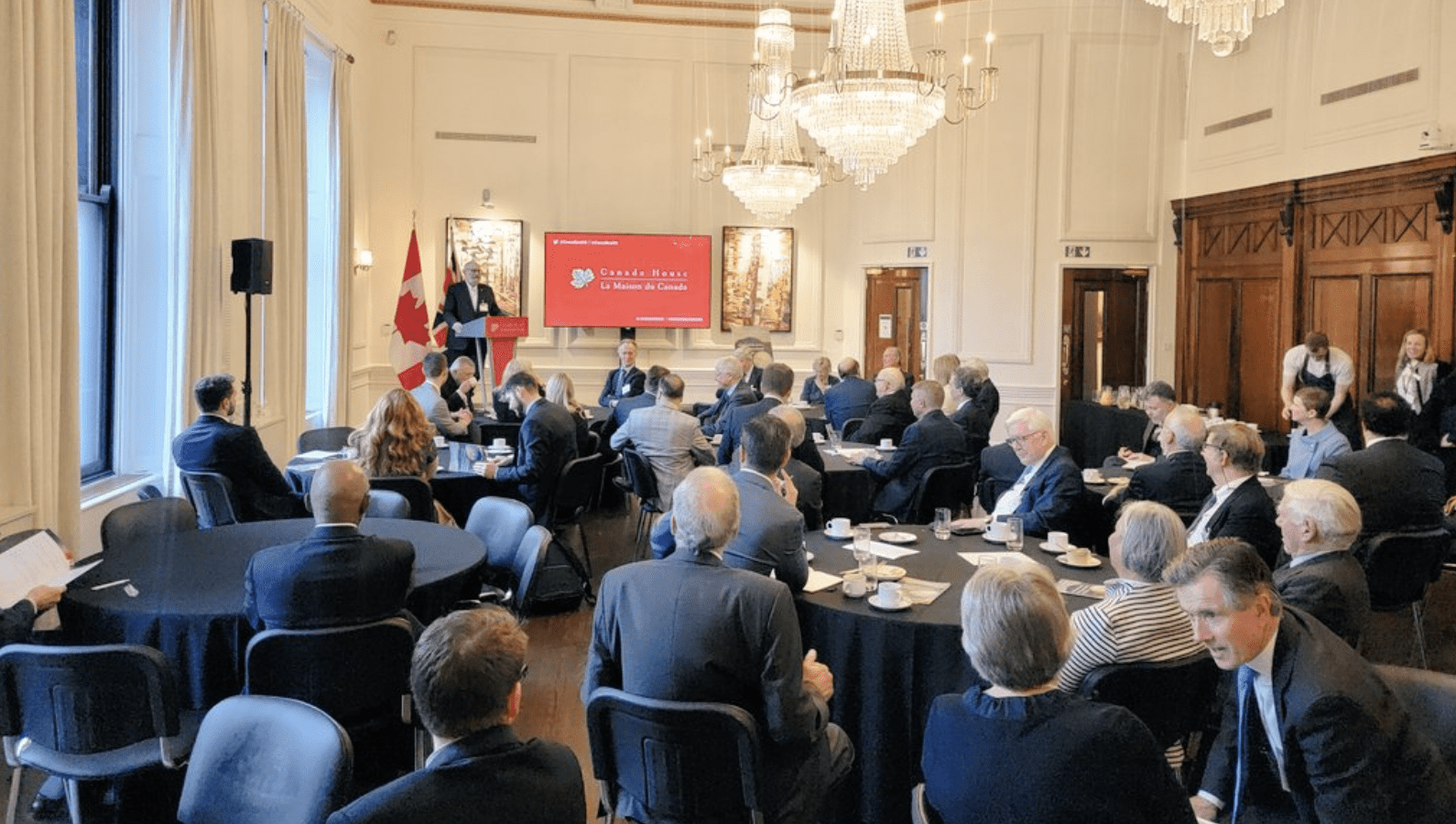

The 50th anniversary Canada-United Kingdom Colloquium, chaired by historian Margaret MacMillan, front left, and hosted by Canadian High Commissioner Ralph Goodale, front right, at Canada House in London/Ralph Goodale Twitter

The 50th anniversary Canada-United Kingdom Colloquium, chaired by historian Margaret MacMillan, front left, and hosted by Canadian High Commissioner Ralph Goodale, front right, at Canada House in London/Ralph Goodale Twitter

Thomas S. Axworthy

December 8, 2022

And London shops on Christmas Eve

Are strung with silver bells and flowers

As hurrying clerks the City leave

To pigeon-haunted classic towers,

And marbled clouds go studding by

The many-steepled London sky

From Christmas, by John Betjeman

All great cities have their seasons. For London, the city where Charles Dickens reinvented Christmas with the publication of his spooky morality fable, A Christmas Carol, in 1843, this is it. When John Betjeman published Christmas in 1954, more than a century and two world wars later, it was as if he was telling the world, “Yes. All of it is still here.”

For the first time since COVID engulfed the planet, I recently endured international travel to attend the 50th anniversary meeting of the Canada-United Kingdom Colloquium (CUKC), convened at Canada House on Trafalgar Square from December 1st to 3rd. Established in 1971, the colloquium brings together politicians, public servants, academics and industry leaders to discuss the key policy challenges facing both countries. I attended in my role as Chair of Public Policy at Massey College, both because the quality of the intellectual exchanges is high and because the anniversary meeting was being held in London, one of my favourite cities in the world. As Samuel Johnson, the 18th century writer said, “When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life.” I was tired of the isolation of COVID, so what better remedy than to return to London?

As with previous meetings of the colloquium, the conference operated under the Chatham House Rule, so the themes can be summarized but quotes cannot be attributed, and my fellow participants aren’t supposed to be identified, though since images of the event have been tweeted, I’ve included those. Suffice to say it drew an exceptional focus group of perspective providers, including historians, academics, current and former politicians, diplomats and policy makers.

As this was the 50th anniversary colloquium, I prepared by reading the report from the first gathering, in 1971, to get a sense of context and compare how the two countries had evolved in the past half century. That year, Britain was preparing to enter the European Economic Community (EEC) under the leadership of Prime Minister Edward Heath, a moderate and visionary Conservative. Just a few years earlier, Sir Winston Churchill had been laid to rest in a state funeral, which reminded the world of the heroic role Britain had played in fighting Hitler’s tyranny.

In 1971, Britain was still a Great Power, or at a minimum a very major one. As America reeled from the combined impact of a brutal decade of assassinations — John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy — followed by the Vietnam War tipping point of Kent State in 1970, London had provided a trans-Atlantic cultural antidote. Through the Swinging Sixties, London was the epicentre of popular culture, with the Beatles and Rolling Stones in rock music, Mary Quant and David Bailey in fashion, Trevor Nunn and Peter Brook in theatre, Julie Christie and David Lean in film, Peter Cook and Dudley Moore in pioneering political satire, and the list goes on. By 1971, London was where every young person wanted to be. I arrived at Oxford to study international relations in 1972.

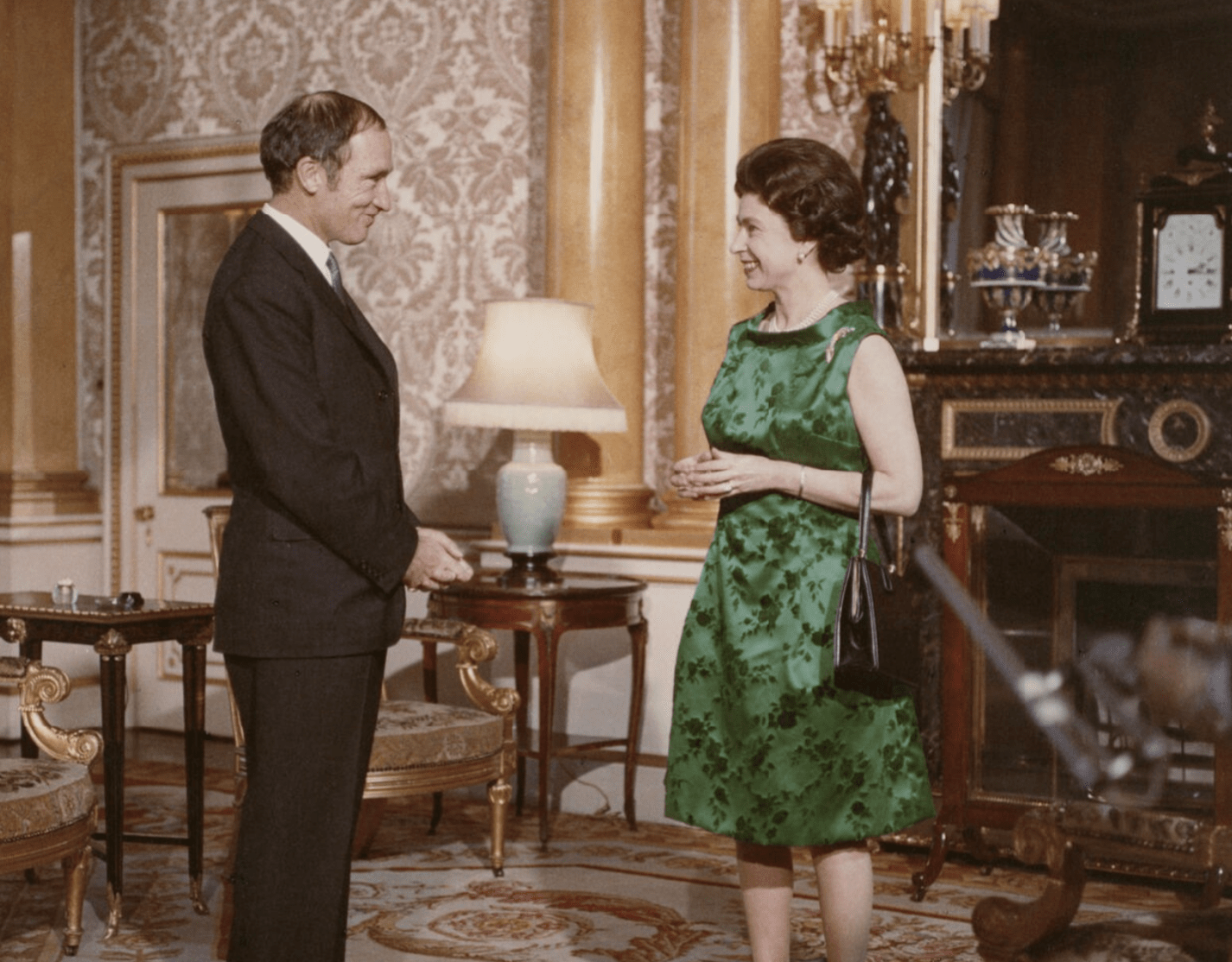

Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and Queen Elizabeth II during the CHOGM in London, 1969/National Portrait Gallery

Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and Queen Elizabeth II during the CHOGM in London, 1969/National Portrait Gallery

Canada had burst into global consciousness with the brilliant Expo 67 World’s Fair and a charismatic new prime minister, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, whom I would later serve as principal secretary. The British tabloids dubbed him “trendy Trudeau” when, at his first Commonwealth meeting in London in 1969, he slid down a banister at Marlborough House and went to Annabel’s, the exclusive Mayfair nightclub frequented by the Rolling Stones. But there was no question as to who was the junior partner in UK-Canada relations in 1971. As Canada was grappling with the complexities of responding to Quebec nationalism, Britain still had the power to amend Canada’s constitution, a leftover from the colonial past that Pierre Trudeau vowed to mothball as Canada began its epic federal-provincial negotiations on the constitution.

These issues are evident in the 1971 report from the colloquium: the British delegation returns again and again to Europe, with hopeful expectations about the economic benefits of entering the EEC, but is wary about how this might affect the Commonwealth and Britain’s world leadership role. Canadian delegates raised federalism and Quebec as an internal issue and how Canada and Britain could best respond to an assertive President Nixon.

Fast-forward 50 years. My oh my, how the context has changed. London is still a magnificent and bustling city but in the wake of Brexit, it isn’t so much swinging as staggering in disbelief. London voted overwhelming to stay in the European Union in the 2016 referendum but was swamped by the anti- Europe sentiment in much of the rest of the country.

Britain is still grappling with how to deal with Europe, putting the Brexit divorce at the centre of every discussion, whether on the economy, political stability or foreign policy. Canada has largely solved — or at least skillfully managed the existential crisis of — Quebec separatism and is moving on to new challenges, including Indigenous Reconciliation. These different paths dominated the 2022 CUKC discussions: British participants described 2022 as an “annus horribilis”, both startling given the parade of political anni horribiles since the Brexit referendum of 2016 and a sort of charming rhetorical nod to the late Queen. Inflation hit a 40-year high of 11.1 percent in October, public sector strikes are on the rise, the pound has lost value against rival currencies, Scotland wants another referendum on dissolving the 1707 Act of Union and Brexit has revived talk of Irish unification. In short, the United Kingdom is not very united.

In response to this UK version of that 21st-century affliction of advanced democracies — the cascade of crises — Britain has suffered a near-political meltdown. One British CUKC participant addressing education policy observed that there had been three prime ministers and five education secretaries in four months. When the latest education secretary was appointed in October, a wag in the department ran her photo with the caption “Employee of the Month”. The current prime minster, former Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak, was described as a safe pair of hands with a firm grip on reality who provides a welcome relief after the tactical misrepresentations of Boris Johnson and inexplicable policy fabulism of Liz Truss. But Mr. Sunak will be using those hands to bail out a ship of state that has been badly floundering.

The two-day CUKC, 50th anniversary edition

The two-day CUKC, 50th anniversary edition

British participants were envious that Canada had secure, comprehensive trade agreements with both the United States and the European Union (the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement came into effect in January, 2021, largely as a post-Brexit damage control exercise) and they placed great emphasis on securing a trade deal with Canada in 2023. These negotiations have received almost no attention in Canada but are crucial to the Sunak government as it needs to show progress on the post-Brexit promise of “Global Britain”. Immigration continues to be a polarizing issue, too: with a population of 67 million, Britain’s immigration target is only 100,000, while Canada, with 38 million, has a target of 500,000 amid political consensus among all major parties that this is the right thing to do. With anti-immigration sentiment the driving force behind Brexit, the issue is far more politicized in the UK.

Britain, of course, still has many major strengths. There was pride among CUKC participants that Canada and the UK are both strong supporters of NATO and aid to Ukraine. The British rightly pointed out that, despite its financial difficulties, Britain has been considerably more generous in development and military spending than Canada. Delegates pointed out, too, that Russia is seeking great power status in the Arctic and China had declared itself a “near-Arctic” power but Canada still seems oblivious to these threats and neglectful of its Arctic responsibilities. Yet, perhaps the greatest change from the 1971 colloquium to today is that British participants now describe their country as a middle power — a term long used to describe Canada but a considerable distance from the glories of Empire that older Britons still remember fondly.

So, Brexit has been a serious own-goal on Britain’s future prospects but we should never forget that this country has a long, dramatic history and it has seen much worse. While CUKC delegates in Canada House were bemoaning post-Brexit trade policy, outside, Trafalgar Square was full of people enjoying the lights of this year’s giant Christmas tree. The 68-foot spruce represents both British leadership and resilience; Norway has sent a tree every year since 1947 in gratitude for Britain’s sheltering of King Haakon the 7th during the Second World War.

Meanwhile, in this challenging year, our British hosts provided wonderful hospitality, inviting the Canadian delegation to a reception at Mansion House, constructed in 1739, and the home to Nicholas Lyons, Lord Mayor of the City of London, (a largely ceremonial/pro bono role as ambassador of the City — London’s financial sector — not to be confused with London Mayor Sadiq Khan’s job). Lloyd George made an important speech at Mansion House in 1911 — when he was chancellor, five years before he became prime minister — saying that Britain would never forget its international obligations. Sunak used the same forum in July, 2021 to outline Britain’s financial future, a year before he resigned as Johnson’s chancellor.

First UK Foreign Secretary Charles James Fox

Delegates also enjoyed an evening at the stately Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, with its magnificent grand staircase and Locarno Suite — where the Locarno Treaties aimed at reducing tension in Europe were signed in 1925 and which was repurposed as the Foreign Office codebreaking hive during the Second World War. As we entered, I saw the bust of Charles James Fox, Britain’s first foreign secretary, appointed in 1782; a special treat as I collected historical prints of Fox during my time as an Oxford student.

Everyone has a favourite London pub: Mine is the Cheshire Cheese

John Betjeman’s Christmas describes how “Provincial Public Houses blaze”. And, so it was as I met old friends at the Cheshire Cheese on Fleet Street, whose cellars go back to Norman days, with a public house on this location since 1538 and an sign saying the premises were rebuilt shortly after the Great Fire of 1666. Samuel Johnson lived close by, Charles Dickens used the establishment regularly and Robert Louis Stevenson once wrote that “a select society at the Cheshire Cheese engaged my evenings”.

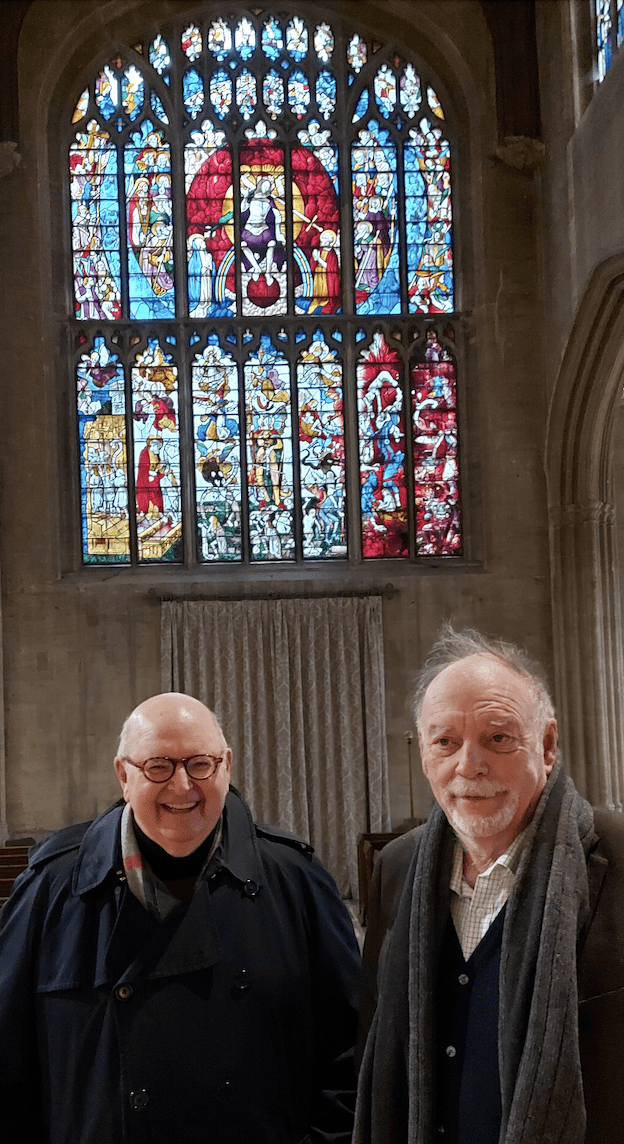

At St. Mary’s with friend Nicholas Fogg

In a later stanza of Christmas, Betjeman wrote, And is it true, this most tremendous tale of all, seen in a stained- glass window’s hue. Indeed, English parish churches — not only the great cathedrals — have the most exquisite art. Betjeman, poet laureate from 1972 until his death in 1984, was so enamored of church art that he once told Desert Island Discs he would want to take with him the bottom half of the West wing pane of stained glass of St. Mary’s church, in Fairford, about an hour’s drive from London. With some English friends we decided to go on a church crawl, instead of the pub crawl that might have excited us more when we were students. We began by going to mass in a little church in Cricklade village, where the base of the baptismal font dated to Roman times and the chancel arch was built in 1120. The congregation, meanwhile, was focused on today, with both prayers and donations offered to help the persecuted in Ukraine.

Then, down the road in Fairford, we discovered St. Mary’s Church, with its 28 windows of medieval stained glass that had so inspired Betjeman. Begun in 1497 in the reign of Henry the 7th, the glass miraculously survived both the Reformation and Hitler’s bombs. Worshiping amid such beauty must surely be good for the soul.

Brexit was a self-induced blow that weakened the country just as it was about to face the rigours of Covid, then the war in Ukraine. But the strengths of Britain are great, its history includes the Magna Carta, the invention of Parliament, abolition of the slave trade and the creation of the National Health Service. The beautiful stained-glass windows of the Church of St. Mary have seen much and in Britain’s future, there will be so much more to see.

Thomas S. Axworthy is Public Policy Chair at Massey College, University of Toronto. Policy Dispatches are pieces combining travel, policy and political writing from foreign datelines.