Note to Zimbabwe: Hold the Champagne

Lisa Van Dusen

November 23, 2017

The world reeled in wonder this week as the kleptocratic rule of Robert Mugabe came to an end in the face of Zimbabwe’s belated addition to the list of countries throughout the Middle East and North Africa that have adopted genuine democracy since the 2011 Arab Spring.

Okay, that’s not entirely true. That lead was actually my first and only attempt at fake news and I can totally see how it could become addictive.

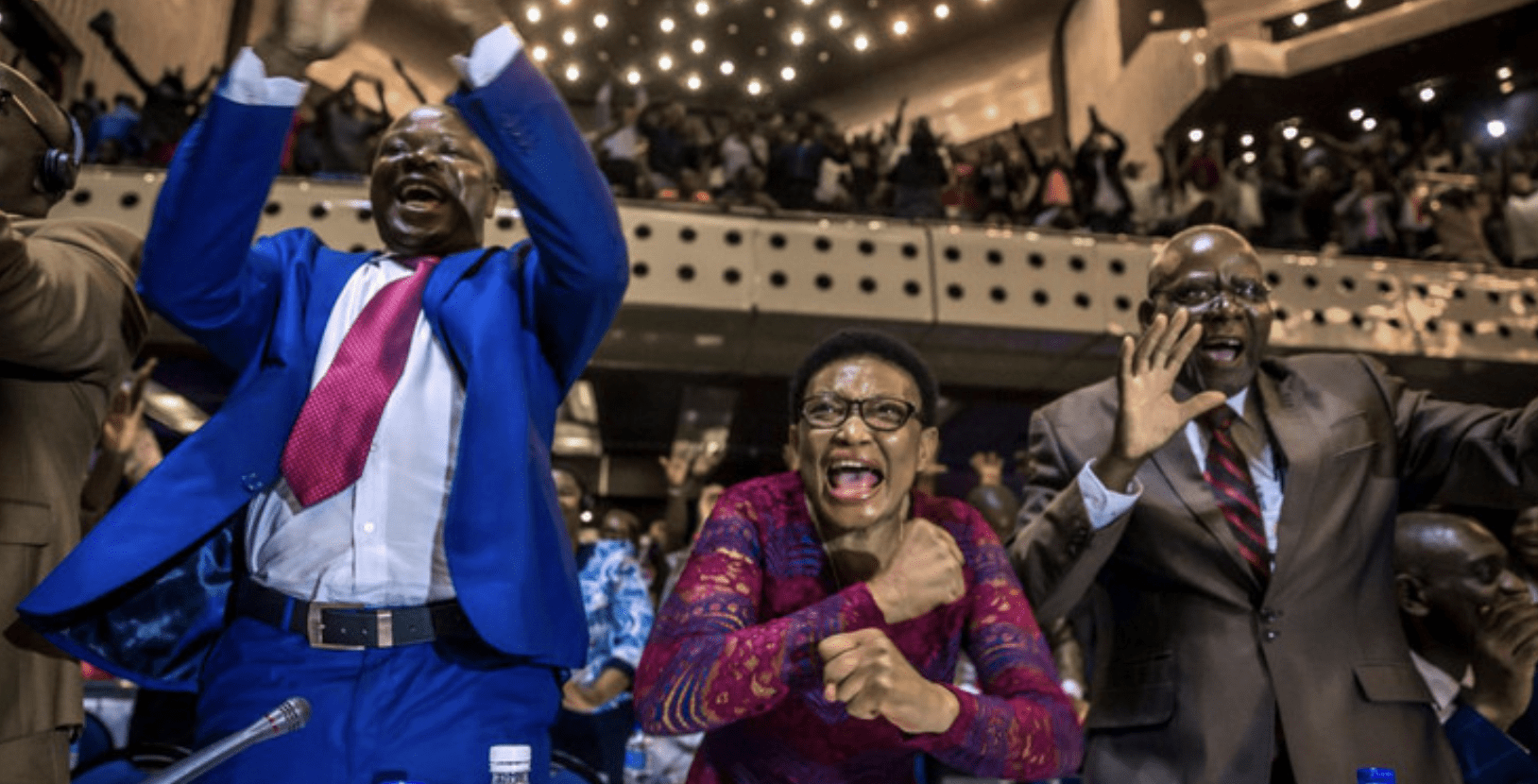

But after nearly four decades, the post-colonial revolutionary-turned-dictator has now left power. Emmerson Mnangagwa, the former vice-president and henchman whose firing by Mugabe earlier this month has given him a legitimacy that would otherwise be compromised by his oppressive record, is set to be sworn in as president on Friday and Mugabe has been granted immunity from prosecution. As euphoric Zimbabweans danced in the streets this week, the hope that their faith in a democratic future won’t be thwarted was overwhelming. But the lessons of other recent post-autocracy transitions in the region have been cautionary.

The emotional roller coaster of the past week as Mugabe refused to resign was reminiscent of what unfolded in Egypt in early 2011 as autocratic president and multiple consecutive 96-per-cent landslide winner Hosni Mubarak delivered not one but two such speeches — one on Jan. 28 and one on Feb. 10 — as the protesters who filled Tahrir Square clamoured for his departure. The demonstrators, soldiers, plainclothes security thugs and everyone watching at home from Dubai to Detroit repeatedly heard the embattled president say everything but goodbye until, on Feb. 11, Vice-President and former intelligence chief Omar Suleiman announced Mubarak’s departure for him.

In Cairo then, as in Harare these days, the military have been cast in the role of saviours — the orderly transitional tool between a dictator seeking to immortalize his grip on power by handing his title to a relative and the promise of a better future, defined for generations as democracy generally and free and fair elections in particular. In Mubarak’s case, the heir apparent was his son, Gamal. In Mugabe’s, his much younger wife, Grace — known for her spending sprees and distinctive approach to conflict resolution.

As we all know, in Egypt and the broader Middle East and North Africa, the early promise of the Arab Spring (notwithstanding the Tunisian exception that belies the rule) was derailed by, in some cases, immediate crackdowns and, in the regionally and culturally crucial case of Egypt, the tactical conflation of democracy with radicalism following the election of the Muslim Brotherhood. The government is now, with Field Marshal Abdel Fattah-el Sisi as president, back in the hands of the military. It is more authoritarian and less democratic than it was under Mubarak based on every metric from freedom of the press to torture to forced disappearances and all the other tricks of tyranny that have been immeasurably facilitated by ubiquitous, extrajudicial surveillance in Egypt as elsewhere.

And, in a narrative motif that’s become ludicrously predictable in stories of political upheaval from Kenya to Venezuela, China’s economic imperialism looms in the background. Beijing, which has propped up Mugabe since he became prime minister in 1980, is Zimbabwe’s largest foreign investor (it is also funding the construction of Egypt’s multibillion-dollar, post-apocalyptic New Administrative Capital).

Days before the Zimbabwean military asserted control over the country on Nov. 14 in an oddball, non-coup coup, its leader, Commander General Constantino Chiwenga, met with senior officials in Beijing. Given China’s view of functioning democracy anywhere as a threat to its own stability, it seems safe to assume that was more about the peaceful transfer of power than free and fair elections.

Policy Magazine Associate Editor Lisa Van Dusen was a senior writer at Maclean’s, Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.