The 4 Percent Solution

Douglas Porter

September 2, 2022

Markets spent most of the week absorbing last Friday’s stern message from Chair Powell, and thus were mostly in retreat until a late-week break courtesy of the key jobs release. Following a carefree two-month rally from mid-June to mid-August, the S&P 500 has dropped for three weeks in a row and is now down by about 7% from the recent peak. The re-reassessment of the Fed’s intentions has largely driven this move, with 2-year Treasuries cresting above 3.5% on Thursday—their first visit above that level since late 2007, and up from less than 3% a month ago. The sell-off at the longer end of the curve has been even more ferocious, as the message of “higher rates for longer” sinks in—10-year yields popped 20 bps this week, at one point pushing above 3.25% after starting August at 2.60%.

The U.S. dollar has caught yet another tailwind from the hawkish Fed, punching above 140 against the yen for the first time since the depths of the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s. Even more notably, the U.K. pound has careened to its lowest level since the mid-1980s (at around US$1.15), when it threatened to sink below parity. The euro has already cracked below parity versus the greenback, although it’s been there before and actually was almost unchanged this week. Even the Canadian dollar has been sideswiped by the broad-based U.S. dollar strength, testing its weakest level since late 2020 at around 76 cents (or $1.31/US$). However, the loonie’s 4% y/y drop is mild compared to the 16% y/y surge in the overall U.S. dollar index.

Friday’s jobs data provided some moderate relief, with payrolls almost landing precisely on consensus at +315,000 in August. While no doubt a solid advance—and completely inconsistent with recession chatter—other aspects of the report sent some calming signals. Wages did not accelerate: Average hourly earnings rose at a moderate 0.3% m/m, holding the annual rate steady at 5.2%. The labour force swelled: The increase of 786,000 was larger than all but two months in the 20 years prior to the pandemic. The unemployment rate rose two ticks to 3.7%, with easing among low-skilled workers. The broad message is that even amid a firm underlying pace of hiring, the extreme tightness in the job market may be beginning to moderate—almost exactly what the Fed doctor ordered.

Helping matters further has been a retreat in energy costs, at least in North America. While oil prices remain choppy, the trend has been erratically downward since the early-June peak. And at under $90, WTI is back below levels prevailing just prior to the invasion of Ukraine. The move in wholesale gasoline prices has been even more dramatic, plunging by more than 40% in the past three months, and now up “only” 10% from year-ago levels (versus increases of more than 90% in early June). Natural gas prices remain quite strong at nearly double year-ago levels (albeit in a different league than Europe), but even these costs simmered down to back below $9/mmbtu this week.

A calming in energy costs would go a long way in dimming recession risks, both by providing some relief for consumers and by toning down the need for an even greater degree of central bank tightening. A small taste of the relief for households could be found in the surprisingly perky consumer confidence reading for August from the Conference Board. This partly reversed what had been nearly a non-stop descent in sentiment over the past year, with the inflation surge undoubtedly the heaviest weight.

The bounce in confidence was one of a number of mildly encouraging U.S. data points this week, mostly stepping back from the recession edge in August. To wit, the ISM factory index steadied at 52.8, jobless claims dipped to a non-threatening 232,000, auto sales held just above 13 million units, and the aforementioned employment gain. While aggregate hours worked dipped 0.1% m/m, they are still headed for a Q3 gain of around 2.5% at annual rates, suggesting that GDP is poised to rebound this quarter after the small pullback in the first half of the year.

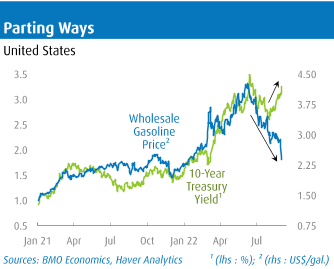

The stabilization of the economy late in the summer is clearly good news from the perspective that recession risks have lightened. However, it also presents a conundrum for the Fed—even as sagging commodity prices have dampened the near-term inflation outlook, a still-sturdy economy implies that they may need to tighten even more than previously expected. This partly explains why energy costs and bond yields are now moving in opposite directions, after almost being in perfect sync for two years (Chart). Indeed, even though inflation looks to have peaked, a variety of regional Fed presidents are now openly discussing the possibility that overnight rates may need to ultimately push above 4% to fully corral inflation. That’s not necessarily a new view—after all, the June dot plot revealed that fully 5 of the 18 surveyed looked for a fed funds rate above 4% in 2023. But policymakers have become a bit more strident in their hawkish views, amplifying Powell’s main message from Wyoming.

While yields did back down from the mountaintop on Friday, the week’s sell-off spilled over into Canada ahead of next week’s BoC rate decision. Two-year GoCs were threatening a test of 3.7% before dipping back to around 3.6%. While few forecasters are openly talking about the possibility of Canadian short-term rates ultimately driving above 4%, the market is nudging in that direction. The conventional wisdom has settled on a 75 bp hike next week, which would take the overnight rate to 3.25%, and some are suggesting the Bank will be nearly done at that point. Market pricing is leaning more toward another 50 bps beyond that, or a terminal rate of 3.75%.

Our official call is for a 75 bp hike next week, and a 3.50% end-point, but with clear upside risks. After all, the entire forecasting world was also calling for a 75 bp move in July, and the BoC delivered 100 bps. On the terminal rate, there are at least three compelling reasons to believe that it may be higher than forecasters and the markets suspect. First, as this space has noted a few times, to fully crack inflation, tightening cycles typically need to see short-term interest rates rise above core inflation—and the lowest measure of core is now 5%. Second, nominal GDP and income growth broadly are on a rampage, and it’s highly debatable that rates just modestly into restrictive territory will be nearly enough to douse this fire. While almost everyone was focusing on the small downside miss in Q2 real GDP (+3.3%), nominal GDP was busily knocking the doors down with a 17.9% surge—aside from a post-lockdown bounce, that’s the biggest rise in more than 40 years.

The third and final reason why the Bank may need to eventually drive rates above 4%—and we emphasize may—is that housing is showing a flicker of life. Just as the Fed was quietly unhappy with the summer rebound in equities—Minnesota Fed President Kashkari gave that game away—the BoC would likely not be pleased to see the housing market stabilize and even revive anytime soon. And, yet, home sales in the Greater Toronto Area bounced 11% m/m on a seasonally adjusted basis last month. Yes, that’s from low levels, and they are still well down from a year ago, and standardized prices are still edging lower. But watch this space in coming months. Any sign that the most interest-sensitive sector of the economy is holding up surprisingly well will be a clear signal that more tightening than expected may yet be required.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.