Brian Mulroney, Then and Now

Of the major policy linchpins of former Prime Minister Brian Mulroney’s legacy, free trade may be the one most closely associated with his personal leadership, conjoining as it did domestic economic policy, bilateral trade policy and the successful implementation of a vision against enormous odds. While Mulroney scrupulously curates his moments in the public eye these days, to call him ‘retired’ would be redefining the word to describe a daily whirlwind of borderless connections and influence. Historica Canada’s Anthony Wilson-Smith, who has known Mulroney since covering him for years at Maclean’s, looks at his journey from Baie Comeau to elder statesman, and chats with the man who has lived it.

Anthony Wilson-Smith

In the summer of 1993, Brian Mulroney was at a crossroads. After 10 years as leader of the Progressive Conservatives, nine as a two-term majority prime minister, he had resigned earlier in the year, consistent with a long-ago vow to serve no more than two terms.

By any measure, his time in office had been consequential, his accomplishments significant, his leadership sometimes controversial, and, by the end, downright unpopular. Now, back in Montreal and committed to no longer speaking out publicly, he alternately considered his personal future away from politics and fretted over the attacks the opposition Liberals were making on his achievements and legacy.

So, when an invitation to lunch came from his friend, the Quebec Inc. titan Paul Desmarais, Mulroney was especially appreciative. Over several hours in the elegant private dining room in the headquarters of Power Corporation on Victoria Square, he listened as Desmarais – the founder of the company and an extraordinarily cultured man with a deep knowledge of history – talked about the need for the former prime minister to allow time and perspective for his achievements to be evaluated in their historical context. What he needed to do, Mulroney vividly recalls Desmarais saying, was to “let the garden grow”; the famous moral of Voltaire’s Candide — “cultiver son jardin” — on the value of narrowing one’s focus to immediate problems that can be resolved constructively.

In essence, Desmarais was telling him to absorb the post-prime ministerial hits in silence – not easy advice for someone used to the constant sparring of politics. But for the most part, Mulroney learned to hold his fire.

The result: today, at 83 – an age he never expected to reach – he is the happiest and most content he has ever been, with no shortage of reasons why.

There is, more than anything else, the presence of Mila – next year marks their 50th wedding anniversary; their four now-adult children, and the 15 grandchildren he sees regularly despite the fact they’re all in Toronto. There is the couple’s spectacular penthouse home, purchased several years ago, atop the Westmount side of Mount Royal, replete with a 3000-square-foot terrace, and a pool at the edge in which he exercises daily with a view of the city below. Add to that the winter home in Palm Beach; regular phone calls and meets with business leaders and current and former political leaders from around the world; and a wide, deeply loyal circle of friends, many of whom date back half a century or more. They include Oscar-winning film director Denis Arcand, music producer David Foster and the singer Robert Charlebois.

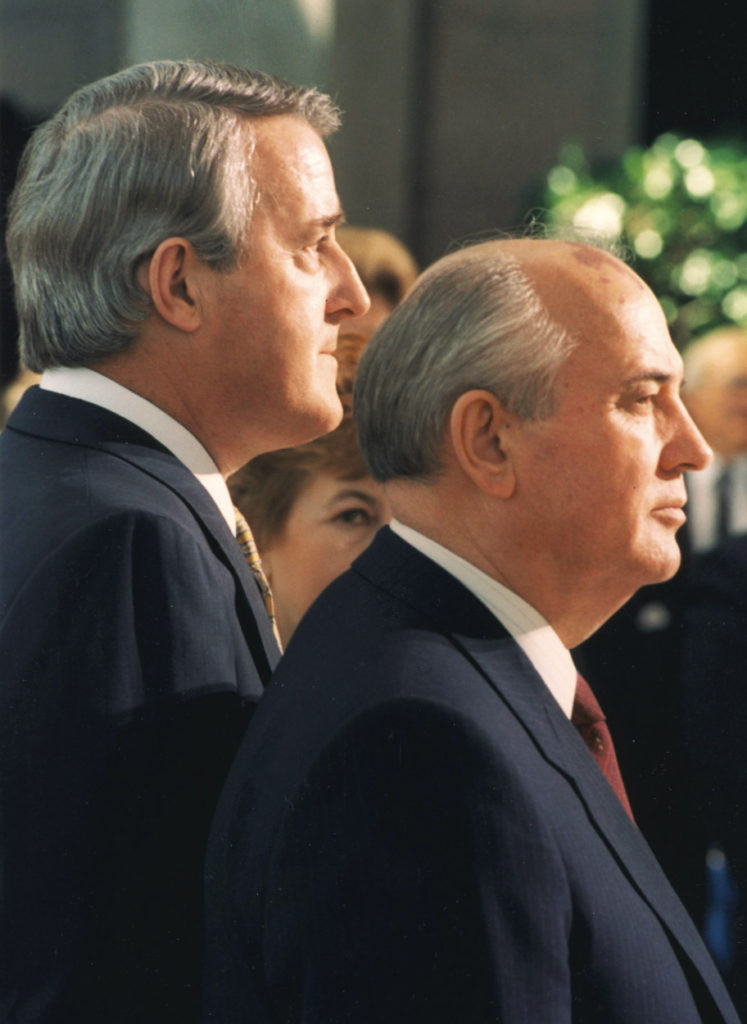

Until the pandemic, he would see Mikhail Gorbachev, the last leader of the Soviet Union, whenever the two men were in the same part of the world. They built a warm friendship when both were in office. With Gorbachev’s passing on Aug. 30 at 91, Mulroney is now the only surviving member of a transformative 1980s club that included Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

When Gorbachev, feuding with then-Russian leader Boris Yeltsin, visited Canada in 1993, Mulroney was advised to not see the former Soviet leader because of an upcoming summit involving Yeltsin. Mulroney rejected the advice , saying “the world still owes this man our undying gratitude.”

Finally, of course, Desmarais was right. Twenty-nine years after leaving office, the key elements of Mulroney’s legacy – including free trade with the United States; the introduction of a federal goods and services tax; early, visionary steps on environmental issues and human rights initiatives – are so entrenched that they’re largely taken for granted. In Quebec, Mulroney is revered even by nationalists (for instance, he has been chair of Québecor Media, owned by the sovereigntist Péladeau family, for many years). Far from being attacked by the federal Liberals, they now, under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, seek his advice on key issues — including the time he briefed the federal cabinet during the highly sensitive NAFTA renegotiation with the Trump administration.

With two near-death medical scares behind him, he has cut back on the lucrative speeches and global travel that were a regular part of life before the COVID pandemic. He mostly works from his study at home and only recently has resumed going in to his Montreal office at the law firm of Norton Rose Fulbright, where he has been a senior adviser since 1993. He still chairs or sits on the board of a number of international companies and foundations in Canada, the United States and abroad. And he remains an inveterate user of the telephone, making and taking calls from around the world at almost all hours of the day. As his longtime friend, the international lawyer and arbitrator Yves Fortier says, with a laugh, “Alexander Graham Bell may be the inventor of the telephone, but it was actually invented for Martin Brian Mulroney.”

By any measure, Mulroney lives an outsized life. That’s not even taking into account the awards and other forms of recognition from around the world, as well as the fact he is the only foreign leader ever invited to eulogize two American presidents — Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush at their state funerals. Add to that Mulroney’s background of decidedly modest means — one of six children growing up in a cramped company house in the pulp and paper town of Baie Comeau, on Quebec’s North Shore, and you have a life story worthy of any rags-to-riches (and power) epic.

As far as Mulroney has come from his early days in Baie Comeau, they still shape him in profound ways. He is widely – accurately – often described as the ultimate insider, with friends at the highest reaches of business and politics around the world. But like his late friend Desmarais, Mulroney is self-made. Desmarais famously started his business career in his hometown of Sudbury, Ontario, and built his first business venture, his father’s bankrupt bus company, into a multibillion-dollar global empire.

Mulroney was obliged early in life to figure out ways to fit in and get ahead. He was a blue-collar anglophone kid in a majority francophone town where most of the small anglo cadre were the bosses; then a boarding student in St. Thomas, NB; then to Nova Scotia for undergrad studies at St. Francis Xavier and, switching languages and provinces, to Quebec City to study law at Université Laval, and on to Montreal, seeking to break into that city’s highly stratified legal circles.

In addition to acquiring flawless colloquial French, those experiences toughened him. He learned how to read a room, analyze the environment, and make the best of whatever situation he was in. Those qualities were invaluable as a labour lawyer, and even more so in politics. He became expert in tactical planning, anticipating events and negotiating agreements both domestically and on the world stage. “Brian,” says his longtime friend and onetime communications director Bill Fox, “is strategically always at least two years ahead of the curve.”

Another important quality Mulroney learned early was generosity of spirit. His dad, Ben, fell ill with the cancer that would take his life at age 62. In his final days, he told Brian, apologetically, “I’m going to have to ask you to look after the family after I’m gone.” Mulroney replied. “I’m already planning that.” He curtailed his busy social life as a young single lawyer in Montreal to move his mother and siblings into an apartment with him.

That desire to help others is constant: there are countless stories about how Mulroney has quietly reached out to provide assistance and advice to everyone from friends to slight acquaintances and even, on occasion, to former political foes. Mulroney called Sheila Copps, his former political nemesis when she was part of the Liberal Rat Pack in the 1980s, to wish her well when he learned she was battling breast cancer. Recently, he helped David Dingwall, another Rat Packer who is now chancellor of Cape Breton University, with a fundraising campaign for the school. Said one person deeply touched by Mulroney’s support during a mutual friend’s health crisis, “His reflex to rise to the occasion when he sees a friend in trouble is like the breathtaking flipside of the cliché about Irish grudges. He was a force of nature.”

Mulroney never talks about such efforts: I routinely hear about such examples from mutual friends. In fact, in 2005, when I was leaving the editorship of Macleans Magazine and journalism altogether, he was one of the first to call to enquire about my future plans. The advice he gave was enormously important in repositioning my career midstream.

Mulroney has always placed great importance on friendships – especially long-standing ones. Fox recalls a day in the 1980s when Mulroney was prime minister. He brought a visiting childhood friend and his son from his hometown of Timmins, Ontario, to meet Mulroney, who dropped what he was doing, greeted them warmly and took time to chat. When Fox later tried to apologize for taking up his time, Mulroney waved him off and said, “Bill, never trust anyone who doesn’t have old friends.”

Mulroney is especially adept, having lived through challenges himself, at helping people during their lowest moments. In 1976, Robert Bourassa’s Liberal government was wiped out by the Parti Québécois. Bourassa, who had been called “the most hated man in Quebec” by one of his own backbenchers, lost his own seat and his political career seemed over. Mulroney took Bourassa to lunch at Chez Son Père, a restaurant on Montreal’s Park Avenue. The advice he gave Bourassa – echoing the essence of what Desmarais would say to him years later – was “Give it time, Robert. In a few years, you’re gonna look pretty good.” Sure enough, Bourassa eventually regained the leadership of the Liberal Party, became premier again in 1985, and by the time of his death in 1996, was revered on all sides of the political spectrum. Less than a year before Bourassa’s death, I spent an afternoon chatting with him in the garden of his Outremont home. He remained deeply appreciative. “Brian,” he said, “believed in me when few others did. I have never forgotten that.”

Along with such kindnesses, Mulroney’s great passion is promoting higher-education learning for youth. The most vivid example is at his alma mater, St. Francis Xavier University, where he has played a key role in raising $105 million for the university’s Brian Mulroney Institute of Governance, founded in 2016. He and Mila gave $1 million toward its founding: at his insistence, it provides scholarships specifically for Black and Indigenous students. Mulroney is about to be honored by his other alma mater, Laval, which announced in June that it is folding its international relations studies into a $100 million faculty named the Carrefour international Brian Mulroney.

Mulroney routinely makes himself available to student groups and nonprofit organizations, often on short notice. (When my son was in high school, the son of an acquaintance wanted to create a political science club. On a whim, he sent a note to Mulroney, with whom he had no connection, asking for help. Mulroney immediately agreed to speak to the club’s founding meeting.) Those education-and youth-based activities, Mulroney said during one of two long conversations we had recently, are his “greatest source of pride” — outside of family — since leaving public life.

Friends observe – and Mulroney agrees – that age has mellowed his combative nature and further enhanced his appreciation of his blessings. “When you come so close not once, but twice, to buying it,” he says of his two life-threatening health incidents, “you think about the positives, and focus less on other stuff.” In person, Mulroney looks fit and vigorous, with his only visible concession to age being that he takes a seat, when possible, during long public gatherings.

In public, Mulroney stays determinedly clear from commenting on partisan politics. He now says the Rat Pack were “excellent” parliamentarians. He is highly complimentary of former prime minister Paul Martin — whom he has known for decades — for his efforts on Indigenous issues, and similarly praises the late John Turner, with whom he clashed so memorably in two election campaigns, in 1984 and 1988.

The one exception is Lucien Bouchard. The sudden defection of Bouchard, often described in earlier years as Mulroney’s “alter ego”, from his Laval classmate’s government during the late days of the Meech Lake constitutional negotiations in 1990 had a devastating effect on the accord, the government – and Mulroney. The two men have been estranged ever since.

That sense of betrayal endures; Mulroney made it politely clear during our talks that he will not discuss Bouchard. But in the tight circles of Quebec, they inevitably cross paths.

In 2011, Mulroney attended the funeral of Audrey Best, Bouchard’s former wife and mother of his two sons, and expressed condolences. In 2014, Bouchard said of relations between the two men: “We run into each other occasionally in Montreal or elsewhere and I think we have an agreement to not embarrass each other.” At the funeral for mutual friend Jean Bazin in 2019, they sat near one another without speaking. After Mulroney gave the eulogy for Bazin (something he says he does “far too often” these days), Bouchard leaned over to a friend and whispered approvingly “he’s still got it.” Most recently, they were at the wedding of the daughter of a mutual friend where they exchanged brief greetings.

This fall, in an event separate to the unveiling of the Carrefour Brian Mulroney, Laval’s law faculty will jointly pay tribute to Mulroney and Bouchard. Their class of 1963 is believed to be the only one in Canada to produce both a prime minister and premier. The faculty will unveil a plaque honoring the federalist prime minister who tried so hard to bring Quebec in as a signatory to the constitution, and the former premier, now back to his roots as a committed sovereigntist (albeit one who believes that option unlikely). It will be a striking reminder of the tumultuous chapter of history the two men lived — first together, then so dramatically apart. The hope of many friends of both men, said one, is that “Lucien and Brian don’t go to their graves without some form of rapprochement.” That, to say the least, is far from certain.

But it would be wrong to suggest Mulroney focuses often on that ruptured friendship. Mulroney says – and other friends agree – that he lives, overall, very much in the now. He confessed to Mila a while ago that for years, his unspoken hope – after his father’s early passing – was “to just make it to 70.” When he achieved that, he switched his target to 80. Now that he is beyond that, he says cheerfully “all bets are off” and he thinks about making each day count.

Shortly after moving into their new home, Mulroney and Mila planned a gathering with friends. With everything in place, they settled on the terrace for a drink – Mila with a glass of wine, Mulroney with his customary soda water. They looked out wordlessly for several minutes at their breathtaking view of Montreal and beyond, lit by a late-afternoon sun.

“Well, Brian,” Mila said, breaking the silence, “you’ve come an awfully long way from Baie Comeau.” They both started laughing. “And that,” says Mulroney, “was when it struck me, maybe more than any other time, how true that is.”

And his metaphorical garden, as Desmarais promised, continues to grow.

Contributing Writer Anthony Wilson-Smith is President and CEO of Historica Canada. A former Editor of Maclean’s, he covered the Mulroney years as an Ottawa and Moscow correspondent, and was previously Quebec-based for The Montreal Gazette.